In 1975, Stock Conversion & Investment Trust Ltd, which owned most of the property in Tolmers Square and surrounding streets, decided that negotiations with Camden on their redevelopment plans were not progressing to their satisfaction. As a tactic to move things along the company decided to evict all the squatters from its properties. One day in March 1975, High Court summonses were nailed on to 23 doors in Tolmers Square and adjacent streets affecting 81 squatters. The Plaintiff was Glennifer Finance Limited, a subsidiary of Stock Conversion. A date was fixed for a hearing in the High Court for 21st March 1975 for possession orders against ‘persons unknown’ who were resident in each property. I was still living in Drummond Street, a London Transport property so I did not receive a summons.

There was much anxiety in the squatting community at the prospect of so many people becoming imminently homeless especially as Camden, we thought, were likely to take over the development anyway. To fight this battle the community came together in a series of meetings and formed many committees – publicity, legal, fund raising and political. Camden Council were sympathetic to the plight of the squatters and persuaded Stock Conversion to postpone the hearing to 25th April.

As the only resident with legal training and working for a law firm I headed the legal committee. I was in the first year of my training contract and not familiar with summary proceedings for possession in the High Court but was about to find out.

I contacted David Watkinson, a barrister from Bowden Street Chambers who specialised in squatting law. He agreed to come to a meeting in Tolmers Square one Saturday to advise us.

At this time, there was no criminal law against squatting (there is now). Taking possession of a property without the consent of the owner was a matter of civil law only and the police did not get involved. The owner could recover possession as long as they followed the procedure laid down in the High Court rules. Evicting anyone, including squatters, without a court order was a criminal offence.

The rules contained in Order 113, Rules of the Supreme Court, required owners to make reasonable enquiries to ascertain the identity of those in occupation. If no one was identified the case could proceed against ‘persons unknown’. If all the requirements of the rules were satisfied, a judge would make a possession order which was binding on anyone in occupation, identified or not.

We went to work on the papers. Luckily for the squatters and my law firm, Offenbach & Co of Bond Street, Mayfair, we were able to take advantage of the Green Form Scheme, the name given to the Legal Aid and Advice Scheme, to provide legal assistance. The Green Form Scheme was so called because the legal aid form consisted of a two page form coloured green. If the applicant satisfied a simple means test on the front of the form, solicitors could provide two hours of legal advice at no cost. I took instructions from all those who had received summonses and got them to sign the green forms.

With advice from David Watkinson, we filed 45 statements or affidavits challenging the evidence of the enquiry agents for the Plaintiff who claimed that they had made multiple visits to each property to identify the occupants, banging loudly on the door each time but strangely in each case, no one had been in at the time.

On the appointed day for the hearing, 25th April 1975, about 50 squatters marched behind banners from Tolmers Square to the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand.

The legal team – me and David Watkinson, assisted by Nick Wates – found our way to the court room where we encountered about 30 lawyers – barristers, solicitors and staff from Stock Conversion – ready for battle.

We three occupied the left hand side of the benches and the opposing 30 the right hand side. The usher called ‘all rise’ and the judge, Mr Justice Croome-Johnson, came in and sat down.

Three cases were heard by the court and although the evidence was challenged each time, the judge was not persuaded and granted possession orders. Then the evidence for one property at 217 North Gower Street was placed before the court and the enquiry agent was called to the witness box. He was questioned about his visits and swore on oath that he had come round to the house three times and each time banged loudly on the front door but no one had answered. He demonstrated how hard he had banged by banging his fist on the court bench in front of him.

The defence then called witnesses – Michael Fitzpatrick, a medical student at the Middlesex Hospital, and Joanna Rose–Innes, a student at the Royal Academy, studying flute and guitar, who told the court that she had been at home practicing the flute on the morning in question and heard no one banging or knocking at the door. This was persuasive.

The case went on until the afternoon and at 3pm the judge gave his judgment. He explained that this procedure under Order 113 was unusual in allowing a case to proceed against unidentified parties. It was essential therefore that the court had to be satisfied that all the technical aspects of the court rules were complied with before granting possession.

On this occasion, having heard the evidence, the judge said he was not satisfied that the exacting requirements had been met so he was dismissing the summons with costs.

Outside the court there was relief and jubilation for the squatters, consternation for the property company and their lawyers. There was no time for the remaining summonses to be dealt with.

The Plaintiffs and their lawyers went off in a great huff but the cases were never restored for hearing……

For a detailed account of this day in court see The Battle for Tolmers Square by Nick Wates, page 180.

Stock Conversion resumed talks with Camden Council and quickly came to a deal. Camden bought Stock Conversion out, having decided to go ahead with its own development.

Camden Council, led by Frank Dobson (later to become MP for Holborn & St Pancras) then had communications with the Tolmers squatters saying in effect our development will be better than the one proposed by Stock Conversion. Most of the houses will be preserved and renovated, new social housing will be built where there are gaps or the houses are unsound and have to be pulled down. You can all stay where you are until we are ready to start work i.e. you will now be licensed squatters. But we invite you to leave in an orderly fashion when the time comes which will not be for a least three years.

This meant that all the squatters were left in peace from 1975 until 1979 when the demolition took place.

It was sad when the time came to leave as it was the end of a unique community. Camden’s development turned out to be a grave disappointment. The terrace of fine but crumbling Georgian houses on the Hampstead Road was replaced by a terrace of new housing, characterised by a long line of ugly, brown grills at street level. Most shocking of all was Camden’s decision to demolish Tolmers Square itself, having decided that they had to build an office block to pay for the rest of the development. The Camden scheme actually ended up with more office space than the much panned Stock Conversion scheme. The new office block of mirrored glass was not an ugly monster like the Euston Tower but was unexceptional. The magnificent houses of Tolmers Square with their balconies and porticos were demolished. The square became a smaller, confusing, misshapen space dominated by the office block and with no obvious exit. It has a tree, a small hump of grass and wheelie bins adjacent to housing of no distinction which has not aged well. The loss of Tolmers Square is a tragedy that resounds to this day and a reminder of the loss of the magnificent Euston Arch which marked the entrance to Euston Station, just round the corner in Drummond Street, from 1837 until its scandalous demolition in 1961.

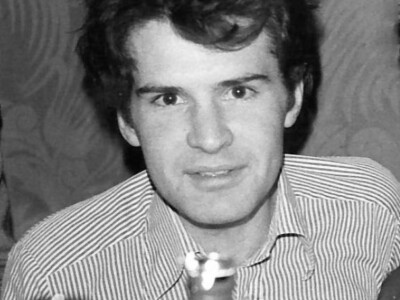

Read more about the author Patrick Allen

More stories

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

Israeli outpost

by Atalia ten Brink

Barry rang and told me he was moving into a squat in Tolmers Square. In Euston, walking distance from the Central. Would I like to join him?

No shame

by Tim Davies

A squat. I didn’t even know what that meant. I had to look it up – in the days before Google. Encyclopaedia Brittanica in those days.

Traveller’s tale

by Rod Smith

Instead I went on a ‘teaching English as a foreign language ‘ course so I could travel the world.

Tolmers united

by Sacha Craddock

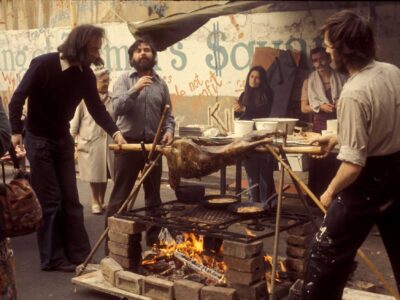

The pleasure of living freely in a world within a world was palpable. The seventies seemed to be very much about differences, collecting together, allowing, encouraging, and tolerating.

Squatting under the bridge

by Andrew Milburn

I chose London because … well, London. I had grown up in a coal-mining town “up north” and wanted to go to the big smoke, where the ground-breaking stuff was happening.