As told to Patrick Allen in 2021

In 1973 I was studying architecture at the Bartlett School, University College London (UCL). Barry Shaw and Nick Wates were friends on the same course. When I went back to UCL for my postgraduate course, I had nowhere to live, so I was ‘camping’ with Barry in his friend’s flat in Islington. Then Nick Wates and Pedro George contacted us also looking for somewhere to live. They suggested that we move into an empty house in Tolmers Square. Nick and Pedro had done a project on Tolmers Square, so they were aware that many houses were empty and derelict pending a commercial redevelopment.

Nick knew we would have to occupy the house as squatters, and we all agreed. We needed somewhere to live, and there were empty houses sitting (and rotting) in Tolmers Square. We identified number 12 as the best choice and decided to move in. The four of us went along one Saturday morning. Barry and Nick were going to go in from round the back and Pedro and I would stay outside, with some mattresses and chairs in a van, keeping watch. We changed the lock to make the house secure, moved in the mattresses and chairs, and that was it. The whole thing probably took ten minutes. We stayed the night, and next day set about cleaning and making the house more habitable.

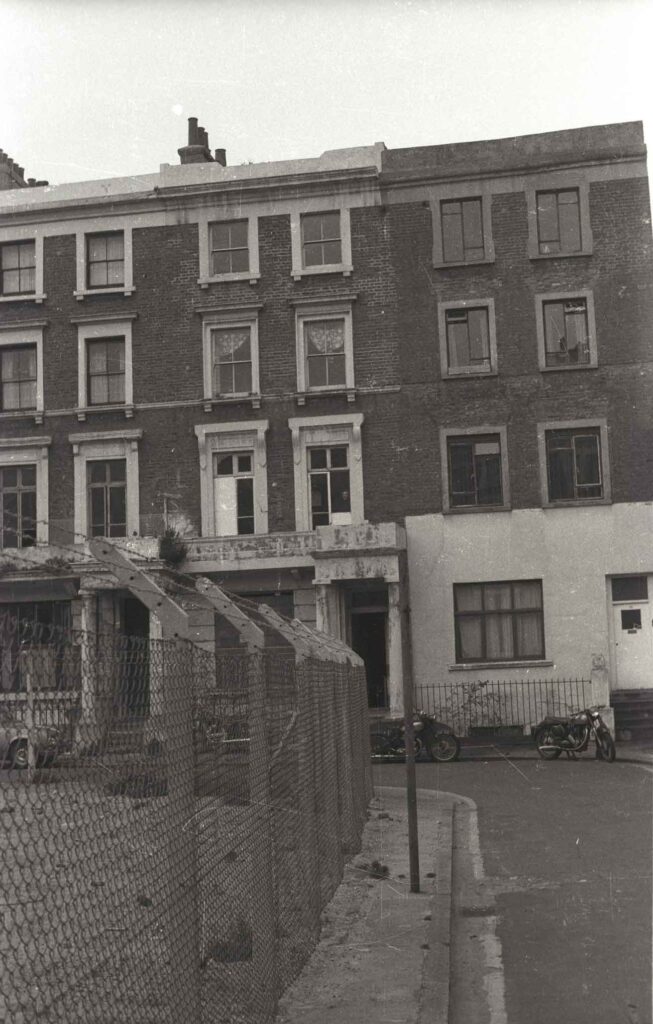

Number 12 was the first squat in Tolmers Square. A few of the houses were still tenanted, but Joe Levy’s company, Stock Conversion, had deliberately let the houses get into an extremely poor condition in order to force the tenants to move out. Once all the houses were empty he would have a clear path to demolition and redevelopment.

The house was damp and stank of cats, the ground floor window was bricked up and there was water but no plumbing. For the first few weeks we just had a cold tap on the end of a hosepipe.

We got the London Electricity Board to switch on our supply. In those days they had a statutory duty to supply to anybody. The wiring hadn’t been ripped out so we were able to adapt it and make it work.

We had an old WC, but no bathroom so I went to the public baths at the Oasis, near Shaftesbury Avenue. This was a fantastic set up. You would go into a cubicle with a big tub then somebody from the outside would fill it up with hot water. It was so deep you could almost swim in it.

Later, Ches constructed a shower in number 12. It was never a great success because it was in a space at the bottom of the stairs, very draughty, dark, with a very claggy curtain, and people walking around all the time. It wasn’t very nice, but at least it worked. It was a cheap way of improvising a shower, with a second-hand Sadia, a shower tray and curtain. We became quite good at reclaiming and re-using discarded furniture and fixtures.

I took the second floor at number 12, and removed the lath and plaster from the dividing wall to join the two rooms together. One room had an enormous reclaimed desk for working and a sofa, and the other room had a mattress on the floor.

We set up a kitchen and dining room on the first floor. It took a few months to get the house straight. In time, number 12 became quite habitable… the kitchen was always a bit Heath Robinson but it functioned.

The first occupants were me, Nick, Barry and Pedro, all architecture students in our fourth year at the Bartlett except Nick who had decided not to continue with the course and was working as the coordinator for the Tolmers Village Association.

To fight the redevelopment, Nick wanted to develop a sense of community and a collective voice in opposition to the development. He headed the publicity campaigns and formed a community association encompassing the ‘legitimate’ tenants and businesses in the area. We all supported this and joined in.

Tolmers Square was getting noticed, and quite soon people would come to us saying “we’ve heard about you, we can’t find anywhere to live, and would like to join you and be part of the squatting movement” and they would often ask where they should go, because obviously we knew the lay of the land.

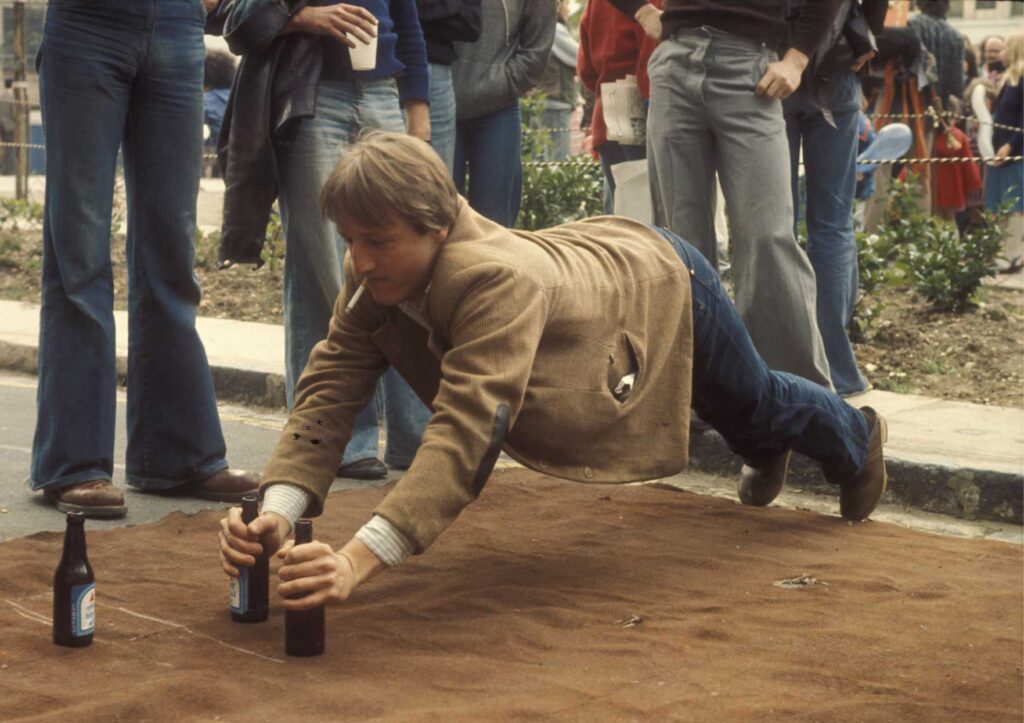

After a few months, a good number of houses in Tolmers Square and Drummond Street were occupied, and we set up the community office there. We got on very well with the local Indian shopkeepers and restaurateurs. They joined up with us because they were also worried about being thrown out by the redevelopment, so they had an interest in being part of the movement. We held social events, and were developing the sense of community that we had aimed for.

By July 1974, only about nine months after we moved in, things seemed to be quite well-organised socially and as a community and our campaign was getting noticed nationally. In fact one of the tabloids made an attack on the “Squatters Army” with a photographs of number 12 (and me) on the front page. The article was total nonsense, of course, and missed the whole point of our campaign.

There was some reshuffling as houses became full. People opened up another house, often next door, or moved in to another house. Each house seemed to develop its own distinct character. There was the one across the square where all the heavy politicos lived. We were less ideological and more practical than than they were. But we all got on well together.

In 1975, the Drummond Street houses came to an end because they were earmarked for early redevelopment. There was a changeover where Sacha, Corinne and Jamie moved into 12 Tolmers Square. Nick and Caroline went off travelling in America, and Barry moved out to number 6.

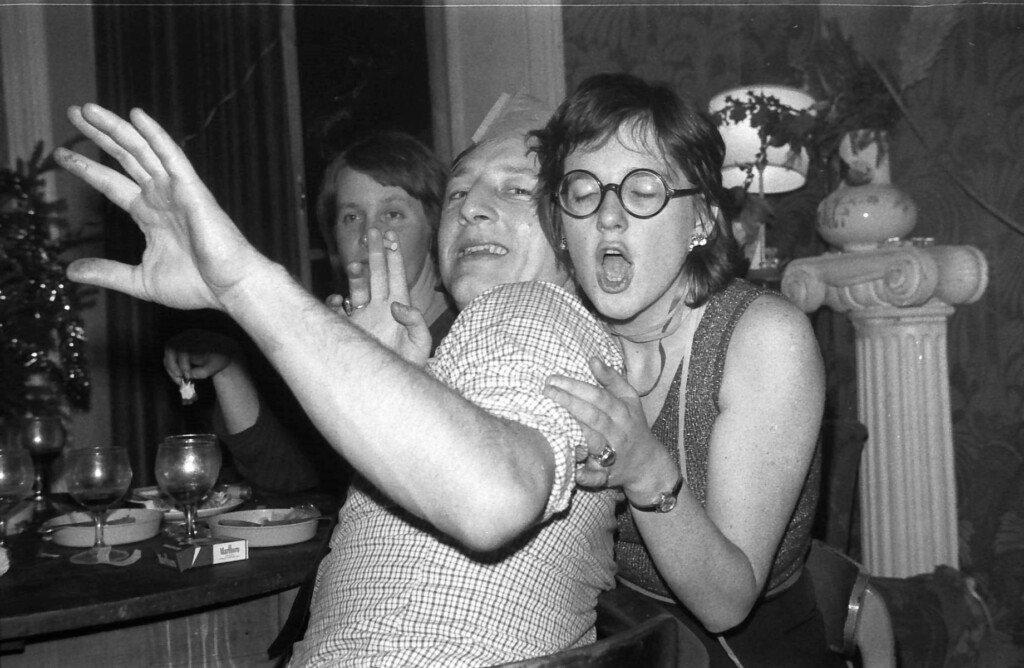

The change of people brought a change of culture to Number 12, most noticeably focussed on very social dinners, with the whole house and visitors sitting down together most evenings to a well-prepared meal. Every one took turns to cook, and it became a bit competitive. We continued our house improvements and put up smart wallpaper in the living room. As more people moved into the area, the social, the political and the community side of it flourished, with events like carnivals and large banquets.

The people across the square were in contact with a number of the leaders of the anti-Communist Party regime in Czechoslvakia, who were organising the resistance from London. They came to me and asked whether I would be interested in taking a free ‘holiday’ in Czechoslovakia, and while I was there, I could do a few little errands for them. We had a camper van, with hidden compartments and went first to Vienna where we changed number plates, then went into Czechoslovakia through a classic No Mans Land with barbed wire and watch towers in a forest clearing. Once in Prague, we dropped documents off and picked documents up according to a pre-determined schedule. And we enjoyed some of the excellent pilsner.

I remember standing under St Wenceslas’ Cathedral clock and waiting for it to ring twice on midday and move away, all that sort of stuff. It was just like in the films, and hardly feels real anymore. We were not told much about the mission in case we were caught and questioned. If we had been caught, we thought we might have been held and thrown out of the country. Luckily, that didn’t happen.

We were in Prague for about four days, and left after all the drops and pick-ups were done. Much later, in 1989 when the Communist Party regime eventually collapsed, the director of the operation in London became Foreign Minister, I think. So perhaps it helped achieve something.

One of the important things about squatting is that you take direct action, focussing on the potential gains without fear of the consequences, perhaps even recklessly at times. I was young and and felt invulnerable, and if I hadn’t been like that, I probably wouldn’t have gone squatting in the first place.

In 1975, Barry Shaw and I finished our studies and went to work at Camden Council architects department. Then in 1976, as I was no longer a student and was earning a salary I moved out of number 12 into a flat I had bought in Delancey Street, Camden Town. But I kept in touch, and number 12 was still the centre of my social life. We went on trips together, most notably to Italy, had lavish picnics on Hampstead Heath in the hot summer of 1976, and many parties. I still felt part of the set-up, the institution. Even now my best, closest friends are from that time, no doubt about it.

What made it special was the sense of purpose, and I think that was important. We all needed somewhere to live, but it wasn’t just a bunch of people doing it for themselves. We all passionately believed that demolishing low-cost housing in central London for yet another anonymous office block was morally wrong and possibly economically suspect. We wanted to make it a political issue, sought publicity and appealed to Camden Council. Our local council leader, Frank Dobson, supported us and eventually, the campaign was successful. Camden Council bought the land, the squatters left and the council built the housing that is there now.

The mixing of very different people in those circumstances was also enjoyable, and worked remarkably well. I don’t think we had too many clashes of personality. There were many different characters, but we all got on very well because of a common interest and the common enemy – Stock Conversion – and the threat of being thrown out. We all had a personal interest, and having a campaign solidified the group. That was an unbeatable combination.

There was room to be yourself too. One of the squatters, Alex decided to give up money. He burned a five pound note and declared that he was going to live on no money for a year. That’s kind of eccentric but also very entrepreneurial – he found that you could go down to Covent Garden, which was still a vegetable market, and get all the left over vegetables. They were perfectly edible, and he would give them away in return for meals.

Squatting was a kind of entrepreneurial act as well. There was a need and there was a place to go, we put the two together and made it happen. I think that’s the other side of it, we were all used to making things happen. We didn’t sit there and wait for somebody to do it for us, we went in and did it. That has stayed with me ever since. I like to be positive, and tend to say ‘yes’ to things, even if there are risks.

Looking back it was one of the best things I ever did. It was definitely one of the most developmental phases of my life experiences. I enjoyed it, and it formed me, and formed my relationships with many people. There are still a number of good friends from that time who I feel very, very comfortable with even after living abroad for over 30 years. I always enjoy seeing them when I go to London and feel that deep down we are still the same people as when we were squatting in Tolmers Square.

Read more about the author Douglas Smith

More stories

Traveller’s tale

by Rod Smith

Instead I went on a ‘teaching English as a foreign language ‘ course so I could travel the world.

Singsongs, meals and Marxism

by Jamie Gough

He said “those two houses are still empty, nobody has squatted them, why don’t you come and live there?” I can still remember that moment.

Tolmers united

by Sacha Craddock

The pleasure of living freely in a world within a world was palpable. The seventies seemed to be very much about differences, collecting together, allowing, encouraging, and tolerating.

Escape from America

by Meg Rosoff

I couldn’t believe my luck and spent the rest of that year in a kind of happy daze. All those amazing people.

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.

The legal battle

by Patrick Allen

Outside the court there was relief and jubilation for the squatters but consternation for the property company and their lawyers.