A little local history

First published as an appendix in The Battle for Tolmers Square, Nick Wates, RKP, 1976

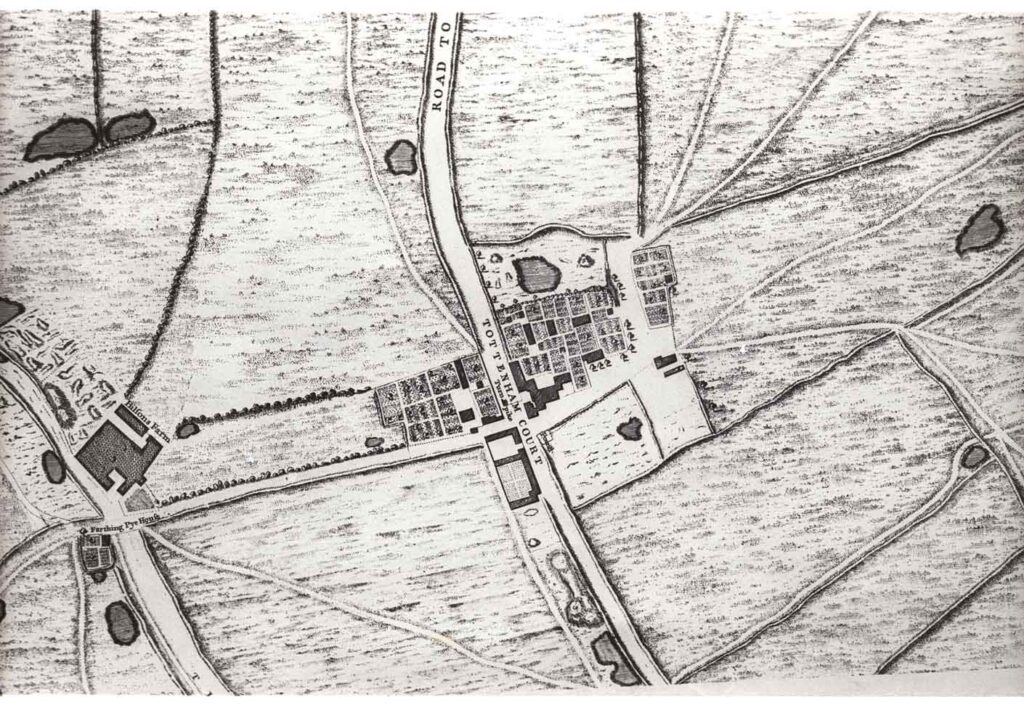

The Tolmers Square Development Area lies in what were the grounds of the large old manor of Tottenhall, or Tottenham Court, in the Parish of St Pancras. Until the end of the eighteenth century the whole area was rural: a newspaper of about 1761 described it as ‘a pleasant village situated between St. Giles and Hampstead’. Development came with the great expansion of London, in the second half of the eighteenth century.

The Manor of Tottenhall

At the time of the Doomsday Book, the manor of Tottenhall was the property of the Canons of St Paul’s Cathedral. The land of the manor covered five ‘hides’ – that is, about 600 acres – and was valued at £4 a year. It was recorded that eight men were living on the land to work it, the whole population of St Pancras in the eleventh century being probably under 300. (At the end of the nineteenth century it was just under a quarter of a million.)

Under the Tudors and early Stuarts the land was leased to the Crown and occupied by royal servants. In 1649, at the establishment of the Common- wealth, the leasehold of the manor, together with other Crown land, was expropriated, and bought by a Londoner called Ralph Harrison for £3,318 3s. 11d. In 1660, at the Restoration of Charles II, it reverted to the Crown and a few years later was made over to the young Isabella Bennet, who also inherited from her father, the King’s favourite the Earl of Arlington, the family seat of Euston in Suffolk. She was married in 1672, when both were still children, to Henry Fitzroy, who was the second son of Charles II and his mistress Barbara Villiers. (The name Fitzroy was often used for the illegitimate children of a King.) On the marriage, Henry was made Earl of Euston, and three years later first Duke of Grafton. Three generations later, the third Duke’s younger brother, Charles Fitzroy (b. 1737), created first Baron Southampton in 1780, inherited the lease on the manor of Tottenhall, while the elder (Grafton) branch of the family inherited the seat at Euston in Suffolk, which they hold to this day.

When inherited by Charles Fitzroy, the manor was still on a lease, periodically renewable, from the Canons of St Paul’s. A remarkable piece of aristocratic sharp practice in 1768 transformed this lease into a freehold. The transaction is described by a writer in the Morning Chronicle in I837:

‘In the year 1768 the Duke of Grafton was Prime Minister. His brother, Mr. Fitzroy, was lessee of the Manor and Lordship of Tattenhall, the property of the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s, London. Dr. Richard Brown, the then prebendary of the stall of Tattenhall, having pocketed the emolument attending the renewal of the lease, and there being very little chance of any further advantages to him from the estate, readily listened to a proposal of Mr. Fitzroy for the purchase of the estate. The thing was agreed, and the Duke of Grafton, with his great standing majority, quickly passed an act through Parliament, in March 1768, diverting the estate, with all its rights, privileges, and emoluments from the prebend, and conveyed the fee – simple, entire, and without reserve, to Mr. Charles Fitzroy and his heirs for ever. The Act states it to be with the consent of Richard, Lord Bishop of London, and the privity of the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s. (2)

The writer goes on to deplore the irresponsibility of the churchmen’s alienation of the enormously valuable freehold in return for a relatively paltry payment of £300 a year. Much of the estate, including most of the Tolmers area, stayed in the hands of the Southampton family until this century. By 1900 the estate had been built over from end to end.

The origin of the name Tottenhall is unclear: it is perhaps derived from a Saxon owner called Totta. The original form Totehele, or Tottenhele, was later corrupted into Tottenhall. and eventually to Tottenham Court. A writer in 1748 noted a tradition that: ‘The elegant village of Tottenham Court belonged to Edward IV. There he kept his beloved Jane Shore.’ (3) It is said that the name ‘Court’ derives from this supposed royal connection.

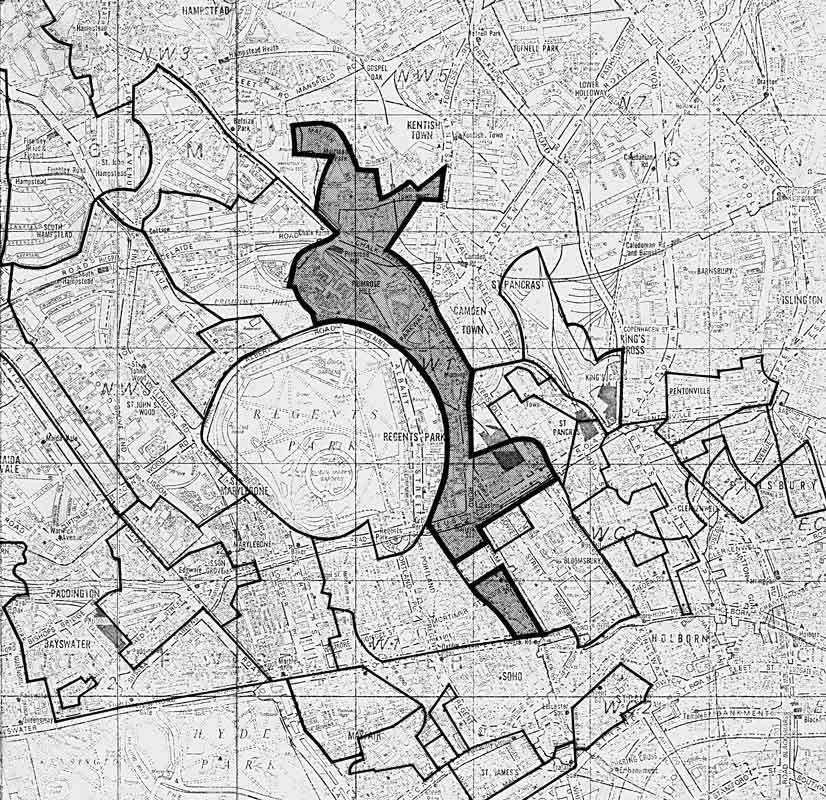

The extent of the manor varied at different times during its history, but consisted basically of a long strip of land along the old Hampstead Road, stretching from Kentish Town, Chalk Farm and Primrose Hill in the north, to Fitzroy Square and down Tottenham Court Road almost to the junction with Oxford Street in the south. To the west the estate bordered on the Crown estate (formerly Henry VIII’s Marylebone Park); to the south-east it bordered on the Bedford Estate and its fashionable development in Bloomsbury.

The Manor House

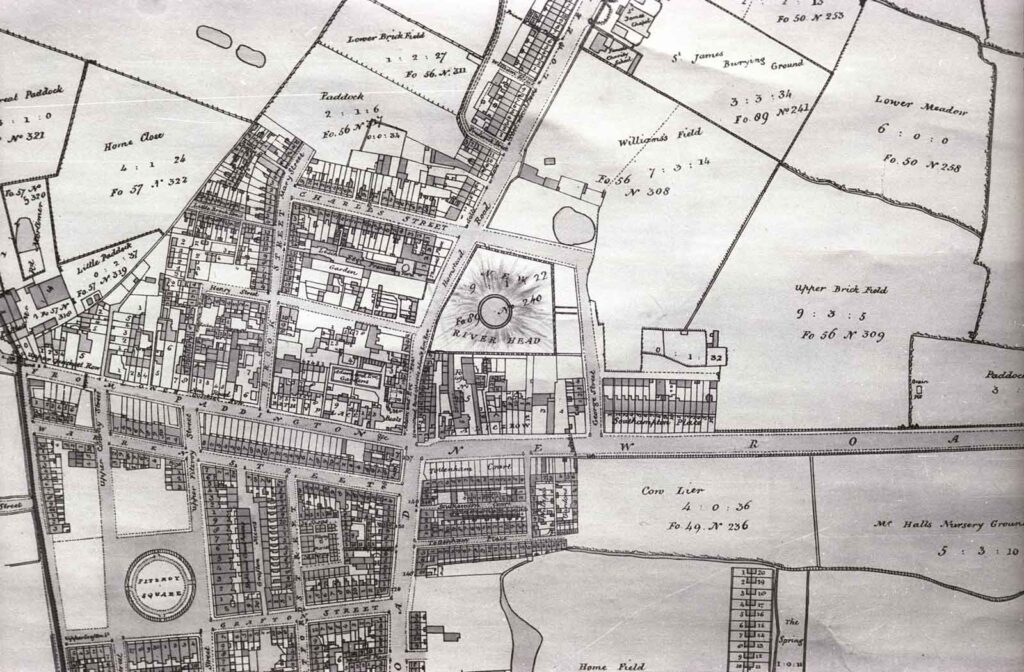

The manor house itself stood to the east of Hampstead Road, between the present sites of Tolmers Square and Euston Road. The position is marked on a plan made by William Necton on 6 April 1591, when the manor was in the hands of the Crown. Necton added a memorandum with some remarks on the building, which was then occupied by Daniel Clarke, Master Cook to Queen Elizabeth. He calls it ‘a very slender building of timber and brick’, which ‘hath been of a larger building than now it is. For some little parte hath been pulled down of late to amend some part of the houses now standing.’ (4) The surveyor also noted that part of the building was ‘very greatly decaied’. From another survey (of 1649) we learn that the house and gardens were ‘moated round’.

This is a water-colour of the house from the Heal Collection made in 1801. The painting is captioned as a copy of a painting of the house done in 1743; and the Elizabethan building was pulled down at about this time. The older (fifteenth-century?) building shown to the left of the Elizabethan block is what was known as ‘King John’s Palace’, though there is no evidence of any actual connection with King John: it was pulled down in 1808. The site of the manor house is now (1976) ingloriously covered by a temporary car park.

Wine, Wenching and Wickedness

While these buildings were still standing, Tottenham Court, as it had come to be generally known by the seventeenth century, became a favourite place of excursion for Londoners. George Wither in 1628 wrote:

And Hogsdone, Islington and Tothnam-Court, For cakes and creame had then no small resort. (5)

The name was well enough known for Ben Jonson in 1633 to characterise a country squire in his play A Tale of a Tub as ‘Squire Tub of Totten-Court’. In 1645 ‘Mrs. Stacey’s maid’ and two others were fined one shilling apiece for the enormity of drinking on the Sabbath day at Tottenham Court. (6)

The best evidence for the character and reputation of the place in the seventeenth century is to be found in a play by Thomas Nabbs, called Totenham-Court, a pleasant comedy, published in 1639. Here Tottenham Court seems to be more than anything else a good place for a cheerful dirty weekend. One character says: ‘A maid at your years, and so near London! . . . The park here hath fine conveniences: or Totenham-Court’s close by: ‘tis suspected that fine Citie ladies give away fine things to Court Lords for a country banquet.’ And a little later: ‘A wench is grown a necessary appendix to two pots at Totenham-Court.’ A few pages later we hear of an elopement, and someone comments: ‘The parson of Pancras hath been here.’ The answer is: ‘Indeed I have heard that he is a notable governor. And Totenham-Court pays him store of tithe. It causeth questionless much unlawful coupling.’

On either side of the Hampstead Road, south of the turnpike on the road north, were two celebrated pubs, the Adam and Eve on the west (first mentioned in 1718, but possibly a good deal older), and the King’s Head on the east. The Adam and Eve was particularly famous for its tea gardens and the boxing matches that took place there, as well as for its cakes and ale. Both pubs are shown in Hogarth’s engraving below.

This century both pubs have been the victims of road-widening schemes – the King’s Head in an LCC scheme in 1906, the Adam and Eve in the Euston Centre scheme. In the 1930s the Adam and Eve was said to have the best beer and the cheapest girls in the West End – so the great tradition lived on.

To the south-west of the present road junction, near where Warren Street is now, were the grounds of the Tottenham Court Fair, famous for its boxing matches and theatrical booths, as well as for the chaos it generated every summer, to the great distress of respectable citizens. In the eighteenth century, various attempts were made to suppress the fair, but it proved tenacious, and not till the nineteenth century was it finally suppressed. The writer of a manuscript in the Heal Collection dated 1808, describes the fair and its suppression with puritanical sternness:

‘Tottenham Court was a place of resort for the lower orders of society, and their successors even now presume at Easter and Whitsuntide to set order and magistracy at defiance. Information having been given upon oath to his majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the County of Middlesex that several lewd and disorderly persons and players of interludes had erected booths and stalls at Tottenham Court in the County of Middlesex aforesaid, wherein was used a great deal of prophane swearing together with many lewd and blasphemous expressions, as also several rude, riotous and disorderly actions committed; eleven of his Majesty’s Justices, having duly considered the evil tendency of such wicked and abominable practices, for suppressing thereof and for preventing the like for the future, granted a warrant . . . for the apprehension of several of the persons concerned in the management of the said interludes, which hath since been put into execution, and the same have been suppressed accordingly and the said booths and stalls pulled down and taken away.’

The New Road

In 1756, the first London bypass road, the ‘New Road from Paddington to Islington’, now the Marylebone, Euston and Pentonville Roads, was built. It crossed the Hampstead Road a little to the south-west of the cluster of buildings that was Tottenham Court. This grandiose new project was sponsored by the Duke of Grafton, and opposed by the Duke of Bedford on the grounds that it would spoil the view from his house and create dust. It seems that the Duke of Grafton was the first to travel on what is now the Euston Road, and, moreover, on a Sunday. One account described the Duke as ‘accompanied by a great company as little sensible of religion as himself’, and another commented that ‘he and his jovial crew on horse back’ passed along as if in triumph over every thing sacred. (7)

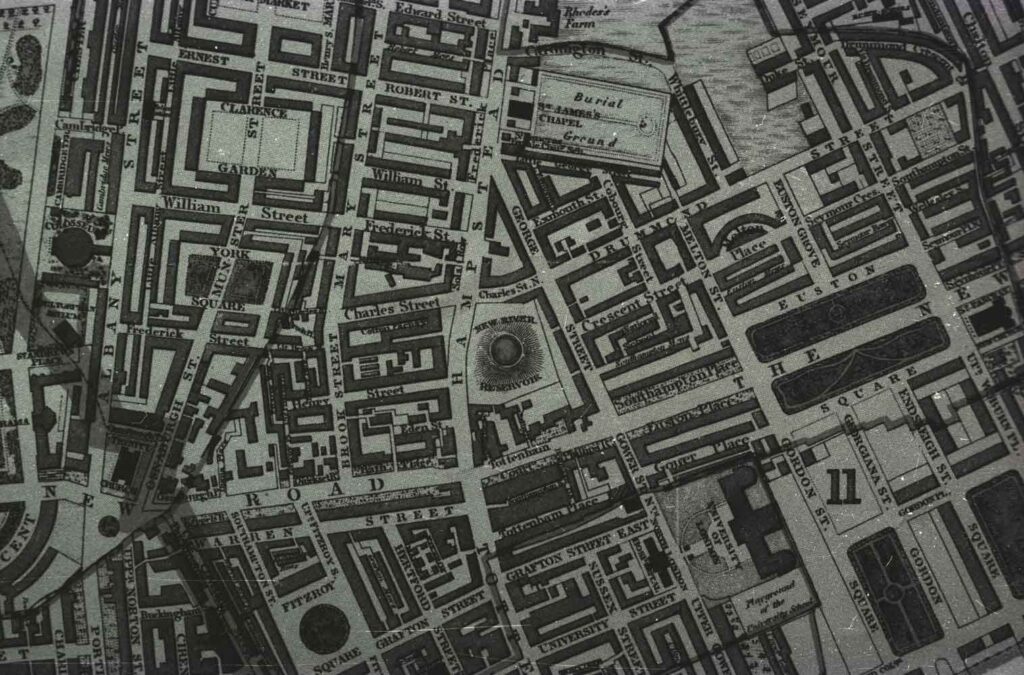

The Southampton Estate development

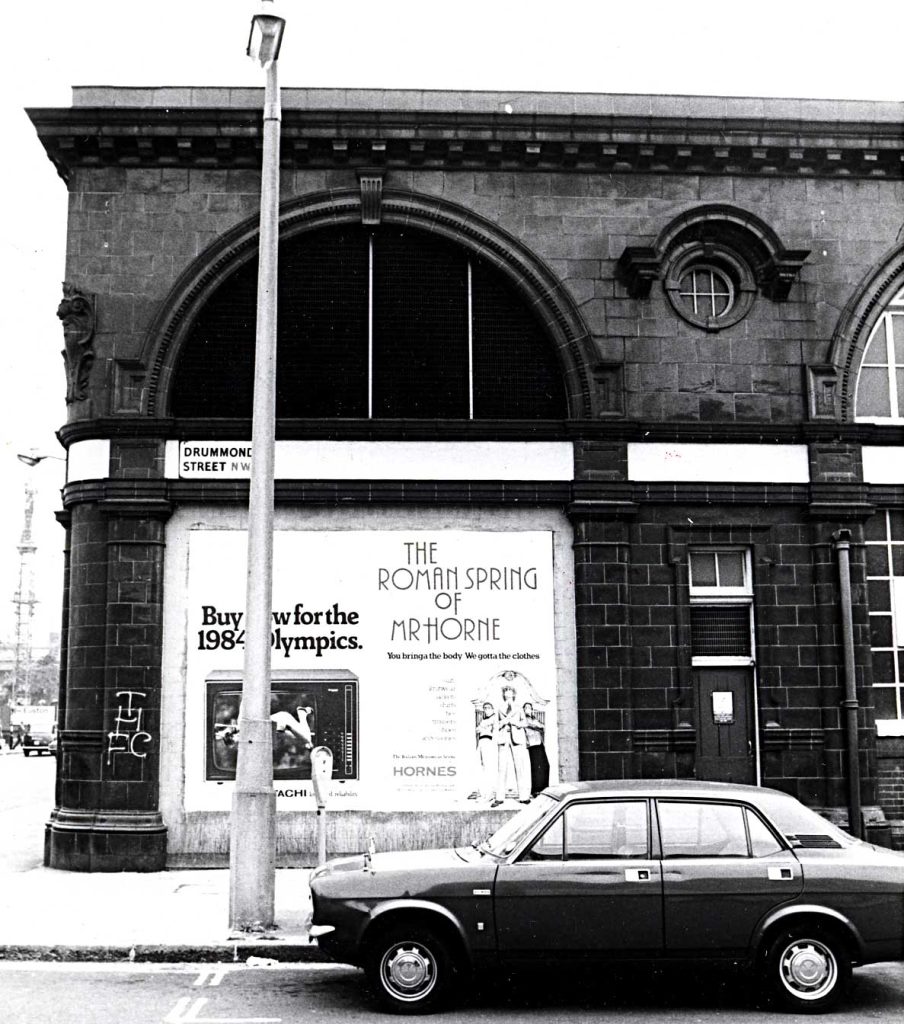

The building of the New Road (so called until 1857) speeded up the development of the area by the Southampton family. The part of the estate to the west of Tottenham Court Road was the first to be developed, in the last years of the eighteenth century (Fitzroy Square was begun by the Adam brothers c. 1793). In the same period was built Southampton Place, a row of elegant houses fronting the north side of the New Road a little to the east of where North Gower Street now is; these houses lasted until the Second World War, remaining socially a cut above the streets to the north. By the turn of the century, new terraces were going up at speed to the west of the Hampstead Road, and soon afterwards the main terraces in our area were built – George Street (now North Gower Street) and Euston Square in about 1810, the smaller houses in Drummond Street and the other streets in the years immediately following. Most of these streets, like other streets on the estate, got their names from members of the Southampton family and families they intermarried with. (8)

The system on which the Southampton Estate, like most of the great London estates, was built over was one that enabled the landowners to develop their land at no financial risk to themselves and with the certainty of a substantial profit only in the very long term.(9) The land to be developed would be divided up into building plots and leased to a contractor, or directly to a builder, for a long period of time – usually 99 years – at a low ground rent, say £5 a year for each house. The builder or contractor built the houses at his own expense, and then normally tried to make his profit by selling the lease. It was a perilous business for the builder, in a flourishing but irregular market; he had to sink a lot of capital into building the houses and took all the risk. At least one of the builders who took a building lease from the Southampton family – a certain George Brown, who built several houses at the south end of what is now North Gower Street – ended up in the bankruptcy courts. At the end of the 99-year term, the land and the houses on it reverted to the ground landlord, who might then renew the lease (at a much higher rent) or else redevelop the now urbanised land to make a further profit. What tended to happen in poorer districts was that towards the end of the original lease term, the houses would degenerate as the tenants ceased to have much interest in spending money to maintain them. This may have happened on the Southampton Estate in the early years of this century. (10)

The streets in the area were built up on this system between 1800 and 1830, and were probably intended for middle-class people – George Street and Euston Square certainly so. But the houses never had the social status of the exclusive Bedford Estate to the south-east: revealingly, among the first tenants of Drummond Street were two coal merchants. The original leases stipulated that the tenants were:

‘not to follow the trade or business of a brewer, bagnio keeper, distiller, pipeburner, melting tallow chandler, working hatter, baker, sugar baker, butcher, poulterer, fishmonger, fruiterer, herb-seller, vintner, victualler, coffee house keeper, dyer, brazier, pewterer, smith, farrier or any other offensive or obnoxious trade . . . on or upon the said demised premises’.

This looks like an attempt to establish for the new houses a similar kind of social exclusiveness to that enjoyed by the nearby Bedford Estate (which had gates at the northern entrances to keep out undesirables and tradesmen); but it never worked and apparently no serious attempt was made to enforce these regulations.

Social decline

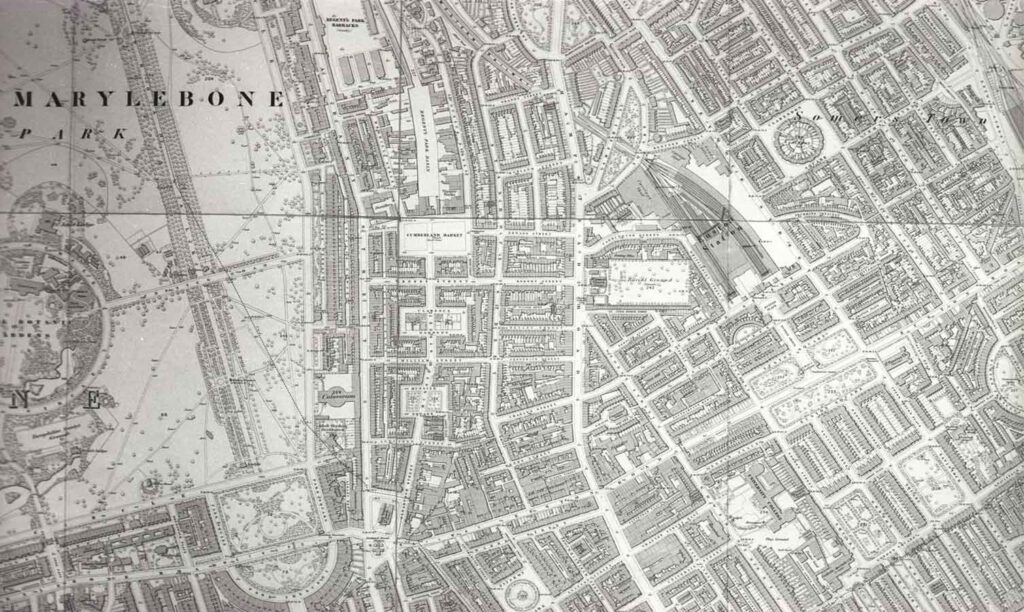

Such gentility as there may once have been, vanished in the social decline that hit all the housing north of the New Road in the middle of the nineteenth century. The decisive factor was the coming of the railways: first, Euston Station (London and Birmingham Railway, 1836), then a little later, King’s Cross (Great Northern, 1851-2), and finally St Pancras (Midland Railway, 1868 –74). The great stations made the areas close to them less salubrious, created a need for housing for the large numbers of men employed in the railways, and above all displaced thousands of people from their homes in the path of the stations and the lines leading into them. St Pancras alone made thousands of people homeless, virtually wiping out the densely populated Agar Town area.

By the end of the century it is estimated that over 100,000 people had been uprooted from their homes by the coming of the railways. . . Modern Londoners, accustomed to the exhaustive compensation and re-housing provisions of publicly controlled comprehensive redevelopment, would find it hard to imagine the impact the railway boom of the 1860’s had on the social and physical environment of the city. It was not only Dickens and his ‘smoke, and crowded gables, and distorted chimneys, and deformity of brick and mortar pinning up deformity of mind and body.’ It was also the migration within the city of a population itself the size of a small city, a population uncontrolled, at the mercy of the laws of the free market and for the most part poverty-stricken in the extreme. . . . Railway building in London simply crowded neighbouring slum properties even more densely and forced up their rents.(11)

Such feeble statutory provision as there was for re-housing of tenants displaced was easily and regularly evaded.

Thus between, and to the west of, the stations a belt of poor and overcrowded housing grew up along the north of the New Road, stretching from King’s Cross almost as far as Regent’s Park. Tolmers Square was towards the west end of this belt. To the north and west, approaching the luxury housing of Regent’s Park, conditions were rather better. To the east was Somers Town, one of the most notorious slum areas of Victorian London. The present isolation of Tolmers Village is a modern phenomenon resulting from the destruction of all the surrounding housing (p. 18).

Tolmers Square

The history of the Tolmers Square site is rather different from that of the surrounding streets. (12) One story says that there was a burial pit on the site at the time of the Great Plague, but there is no real evidence to support this story. In 1802 the New River Company, a company which worked an artificial waterway from Hertfordshire to the New River Head in Islington, took a lease on the land and converted it into a reservoir for the supply of water to west London.(13) In the 1830s an Artesian well was sunk on the site: the appearance of this was a large grass-covered mound.

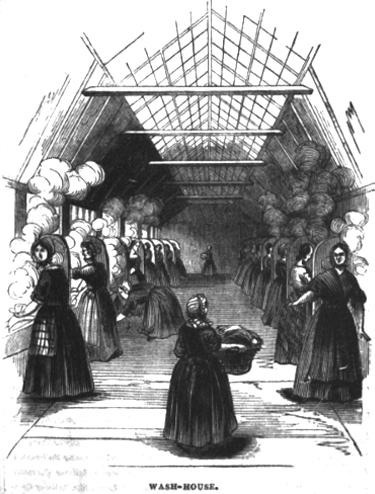

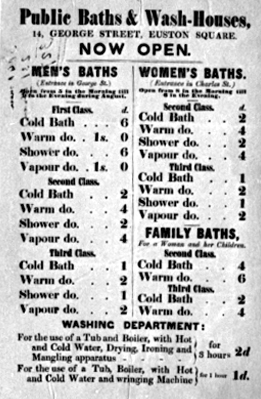

In the 1840s a complex of public baths and wash-houses for the poor was built on the north-east corner of the site, served by water from the reservoir. A writer in a contemporary newspaper was enthusiastic:

Pent up by their occupations in the midst of London, a large proportion of its vast population can only on rare occasions find time to go to the necessary distance to obtain the advantage of a bath and the comfort of a clean skin: and when they do so they find the greatest impediments in their way. They are now prohibited from bathing in the Thames. The Lea and Serpentine Rivers are only open to them at particular hours. The comfort of a warm bath is placed out of their reach by its costliness, and to procure a warm bath at home, which is never thought of except when disease make it necessary, is almost an impossibility. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that they scarcely ever indulge in a practice so essential as bathing to the health and to the full enjoyment of life. . . . The corporations of Liverpool have lately built baths and wash-houses for their poor. . . . It is proposed to carry out in London on an extensive scale the plans of which the success and usefulness have thus been confirmed. . . . (The first of these model establishments has just been completed in St Pancras. In that populous district the Society for Establishing Baths and Wash-houses for the Labouring Classes has been enabled by the liberality of the directors of the New River Company to procure at a nominal rent an excellent site for their establishment on a portion of vacant ground at the base of the reservoir in the Hampstead Road. We have visited the baths and wash-houses and have pleasure in bearing witness to the excellency of the arrangements. (14)

However, in spite of the worthy efforts of the Society for Establishing Baths and Wash-houses for the Labouring Classes, it seems that the Labouring Classes were not altogether eager to take advantage of the excellent arrangements offered to them. In 1859 the wash-houses were closed. A little later the mound above the reservoir was levelled and the earth was carted to Regent’s Park.

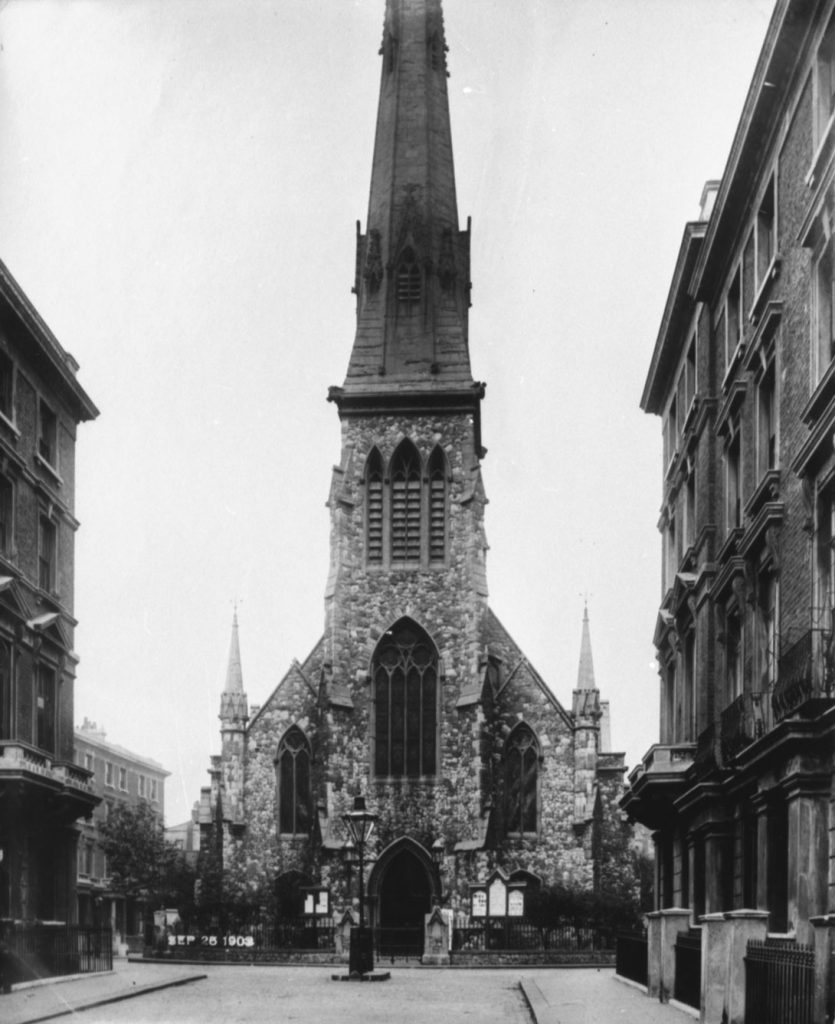

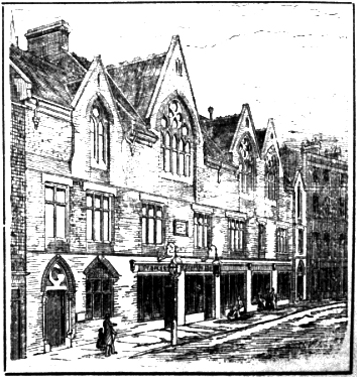

The houses in the Square were built by a builder called William Sawyer between 1861 and 1864 (See David Gedye story) . Simultaneously the Tolmers Square Congregational Church was built in the middle of the Square; this was a Gothic edifice designed by John Tarring (an architect known as ‘the Gilbert Scott of the Nonconformists’ from the large number of Nonconformist Gothic churches he built in London). The church, which had a spire at the west end some 120 feet high, was highly praised by the contemporary press: one newspaper described it as in a style ‘somewhat after that of the House of Commons’. The name ‘Tolmers’ was taken from a small village in Hertfordshire, near the source of the New River.

It is fairly clear from the architecture that the houses in the Square were intended to be rather more ‘genteel’ than the streets to the east: in fact it is said that originally there were gates at the entrance on the east side to the scruffier Drummond and Euston streets, the main entrance being from the rather more affluent Hampstead Road. But this did not really achieve its intended effect of isolating the Square from the poorer housing to the east, and within a few years of being built, though some ‘posh-ish’ people did live there the tall houses in the square had mostly degenerated into multi-occupation and overcrowding nearly as bad as the rest of the area. In the 1871 census almost all the houses are in multi-occupation and there are 364 people recorded as living in the 28 houses.

Tolmers at the end of the nineteenth century

Charles Booth at the turn of the nineteenth century wrote of the church that it

‘finds it something of a struggle to exist in so unpropitious a neighbour-hood’.(15) The area attracted a variety of charitable institutions, such as a large-scale soup kitchen in the Euston Road, a Salvation Army post in Tolmers Square and a Baptist Mission in Drummond Street. The most notable of these was the Tolmers Square Institute, an appendage of the church built in 1877 for meetings and good works. A contemporary press cutting gives some idea of the character of the area at the time in a way that was probably only a little melodramatic;

‘Thousands of young men and women are living in the large houses of business very near to Tolmers Square Institution, also thousands of men employed on the Midland, London and North Western, North London and Metropolitan Railway live about here, and it is to gather such and influence them for good that the Tolmers Square Institute, People’s Cafe and schools have been erected. . . . The scene of the Euston Square murder is within a few minutes of the Institute, and recently, within a few yards, a man hacked his wife to death with a hatchet. More than one child has been found dead within the railings of the church, one with its throat cut. Wickedness abounds, and Tolmers Square Institute has been built to try and stem this torrent of iniquity.’ (16)

At the end of the last century the area was certainly rough, increasingly so towards the east. In Booth’s general survey of north-west London he wrote:

By far the worst area of poverty is that between St. Pancras Station and the Hampstead Road, extending in places to Albany St. Any improvement here is due to displacement by railway extensions. The people are low rough labourers mixed with costers and prostitutes. . . . The missions have maintained a stream of charity, and the railways, with the growth of the great furnishing shops in Tottenham Court Road, have helped to provide work. Thus supported, and clinging to their accustomed surroundings, the people have crowded every house within reach, and filled from cellar to roof whatever new buildings have been provided. The result has been to raise site values, and of late there has been little or no fresh building. Extravagant claims are made by the owners of slum property, and every scheme of improvement hampered. Crowding is chronic, and the instances of excessive overcrowding that have come to light are appalling. (17)

Of the overcrowding we have statistics: in the streets comprising what is now the Tolmers Square development area, according to the census of 1871, were living some 5,200 people. (Compare with this a population of about 600 in 1971.)

Not all streets were equally bad; Booth gives the following breakdown:

Well to do: Hampstead Road, Southampton Row (Euston Road), Euston Square. Fairly comfortable: George Street, Euston Buildings.

Poverty and comfort mixed: Tolmers Square, parts of Euston Street, Drummond Street.

Moderate poverty: Exmouth Street, Coburg Street, and various sites tucked in behind the main streets.

Lowest class: Little Exmouth Street, Little George Street.

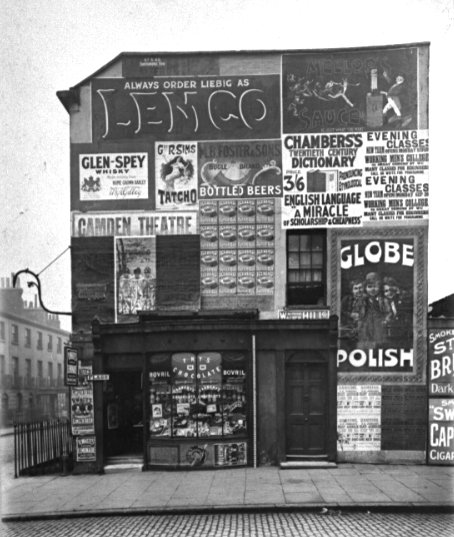

This is in fact a rather better picture than some of the other evidence might lead us to expect. It seems that some quite well-off people continued to live in the area, which was never socially completely homogeneous. In some of the houses in George Street and to the west the 1871 census notes the presence of servants. This photo of Tolmers Square, taken in 1903, certainly does not seem to show a slum.

To sum up, we may describe the social composition of the area as predominantly rather poor but with a scattering of more prosperous families towards the west. People who grew up in the area early this century certainly remember a sharp contrast between the ‘posh end’ and the ‘rough end’.

The main sources of employment at the end of the century were the railways (including the Metropolitan line, built along the line of the Euston Road in the early 1860s), the furniture shops in Tottenham Court Road, and the rag trade: a very high proportion of the women in the 1871 census described themselves as seamstresses – though considering Booth’s remark about prostitutes that may have been something of a euphemism in many cases. As well as these major employers there were a lot of small businesses and craftsmen flourishing in the area – bookbinders, jewellers and so on.

The twentieth century

In most respects the history of the area this century is one of a slow disintegration, accelerating around the time of the Second World War and afterwards. The land passed out of the hands of the Earls of Southampton and the New River Company and into those of a variety of landlords, big and small, more or less anonymous. Some of the worst streets – Little George Street and Little Exmouth Street – were cleared for an LCC school. Extensions to Euston Station wiped out others. Everywhere the population slowly declined as commercialisation spread into what were formerly residential areas. The housing stock was further reduced by Second World War German bombing.

In Tolmers Square, half of the south side was taken over by a pharmaceutical company and converted to factory and warehouse use. The church finally gave up the struggle to exist and closed just after the First World War. The building was converted into a popular and lively, but not at all elegant, cinema (1923), which lasted until 1972, when it was bought by Stock Conversion and closed. (Local legend has it that the church had to be deconsecrated after the minister of the church hanged himself over the altar. This would explain the famous ghost of the cinema. Two of the staff claimed to have seen a bright light appear at four in the morning behind the screen where the old altar used to be. The light moved up the aisle to the foyer and disappeared. As a result of this the night watchman used to go for a cup of tea at Euston Station at this time. The spire was pulled down at the end of the 1920s and the trees which used to surround the church disappeared. All this finally put paid to the Square’s pretensions to gentility.

Physically, the area continued to evolve in a piecemeal fashion. Buildings were converted for new uses, extensions were added, and backyards filled in to cater for increasing numbers of commercial and small industrial firms. Several new buildings were erected where old ones failed to cater for new needs, or to fill in bomb sites. Most of the new units were for commercial purposes: architectural studios, a TGWU headquarters, a London Transport generating plant, company offices. The only new housing built this century was the Cecil Residential Club, a charitable hostel for girls. This building, designed by Maxwell Fry in the late 1930s, actually won an RIBA architectural award. (18)

From about 1920 onwards, many of the long-established residents started to move out to more spacious parts of London. They were replaced by immigrants of many nationalities. It seems to have been an area where newcomers to London would come and live for a few years, then, as they became established, they would move out to (literally) greener pastures. After the Second World War there was a strong Greek and Cypriot population, then from about 1950 some Asians began to move in, transforming Drummond Street with their grocery shops and restaurants into a colourful and lively commercial street.

Socially there were tensions and divisions. In general the western end was the ‘posh end’, as opposed to the east (by the station, and towards Somers Town). In addition, there were several owner-occupiers, in North Gower Street in particular, struggling to maintain a ‘respectable’ existence in a declining area. There were divisions between the nationalities, and between tenants and owner-occupiers. Between the wars, children from the south side of Tolmers Square (where there were owner-occupied houses) were forbidden to go to the houses on the north side, where the people were mostly tenants. A woman who grew up in Tolmers Square remembers as a child being so ashamed of her address that she would tell people she lived in North Gower Street. People who are asked to give their memories of what the area was like in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s tend to come back to the same themes: it was a rough area with regular fights which the local children would stand round and watch; it was full of alcoholics, prostitutes, and gambling clubs – an atmosphere like that of the areas round other major stations; conditions were often squalid and the people generally poor. By the mid-1930s the buildings were already falling into disrepair, and little was spent on their upkeep. On the other hand, especially for people who lived there between the wars, it was a ‘place with atmosphere’, a place full of colour and variety: ‘Railway, shops. Market. Self-employed. You name the trade or service and you would find it in this area.’ And when people are asked how it has changed, there is one metaphor that keeps recurring. In the words of the policeman whose beat it was in the 1960s, ‘the area sort of died’. Whatever else the 1970s have done to Tolmers, they have brought it back to life.

Notes

(1) There is not much original research in this account, although the history of the manor of Tottenhall has never been thoroughly treated. The indispensable sources are the relevant volumes of the London County Council Survey of London, the Heal Collection of manuscripts and documents in Swiss Cottage Library, and the records of the manor in the Greater London Record Office. I have not seen the private records of the Southampton family.

(2) Quoted from W. Howitt, The Northern Heights of London (London, 1869). On the transaction see also Commons Journals, vol. 31, 1766-68 (1803), pp. 639, 647, 655, and Survey of London (London, 1900 etc), vol. 19, p.12.

(3) Stukely, manuscript volume of memoirs, quoted from C.H.Denyer (ed), St Pancras through the Centuries (London, 1935), p.24.

(4) Survey of London, vol. 21, p.120.

(5) In his Britains Remembrancer (London 1628), fol. 120 b.

(6) See W. Wroth: The London Pleasure Gardens of the eighteenth Century (London, 1896), pp.77–80.

(7) C. Lee in Camden Journal (Libraries and Arts) April/May 1972.

(8) See G. Bebbington: London Street Names (London, 1972) pp. 132-3. There are articles by John Stansfield on the local streets in Tolmers News, no. 8 and 10. On the Fitzroy/Grafton family see B. Falk, The Royal Fitzroys (London, 1950).

(9) See John Summerson: Georgian London (Harmondsworth, 1962), ch. 3.

(10) Compare Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London (London 1902–3) series III, vol. I, p.189:’When a lease nears its termination no money will be spent that can possibly be avoided, and when it is anticipated that the site will shortly be wanted, coming events cast their shadows before them. It may be for the extension of a business premises such as Maple’s, or for the further enlargement of Euston Station, or by the local authority for widening a street or opening up a slum. But though all in themselves good objects, their shadow is the shadow of death.’

(11) Simon Jenkins: Landlords to London (London, 1975), pp.107–8.

(12) See also Simon Hodgkinson: History of Tolmers Square, unpublished manuscript essay (copy in Swiss Cottage Library).

(13) Information kindly supplied by the archivist of the Metropolitan Water Board, Mr G.C. Berry. See also F. Miller: St. Pancras Past and Present (London, 1874) p.164.

(14) Cutting in the Heal Collection.

(15) Booth: Life and Labour, series III, vol. I, p.185.

(16) Cutting in Heal Collection.

(17) Booth, Life and Labour, Series III, vol.I, pp.195, 187-8.

(18) See N. Pevsner, London II (Buildings of England, Harmondsworth, 1952)