The man who built Tolmers Square – by his great, great grandson

I first became aware of Tolmers Square in the late 1950s when I overheard my father discussing problems his mother had with compulsory repair orders that had been served on property she owned in London. It was a wow moment learning I had a grandmother who owned property in our capital city. Regrettably it wasn’t a road to riches but it was, however, the beginning of a road of discovery relating to the building of the London we know today, but I get ahead of myself. In the late 1950s I was still a schoolboy whose horizons were hemmed in by the hills surrounding the Scottish town of Pitlochry, where we lived. My forays south had been no further than holidays in Whitley Bay where my paternal grandparents lived, but that was soon to change.

In 1966 my elder sister worked in Shell House and shared a rented flat in Hampstead. With a guaranteed floor to sleep on I treated myself to my first flight and flew from Glasgow to Heathrow for my first visit to London. A visit to Tolmers Square was on my “to-do” list. I wasn’t sure what to expect and recall my surprise when I saw the unexpected sight of the rundown cinema in the centre of the square. As I looked around, the early signs of dilapidation, the reasons for the compulsory repair orders, were evident. I took some photos of the properties we owned, avoided the – “What’s he up to?” – stares from residents, and left.

I sent copies of my photographs to my grandmother and headed off to university. Less than twelve months later my grandmother died and her three properties were inherited by my father, who lived in Scotland, and his sister who lived in Whitley Bay. London was a long way away to own problematic rental properties and in 1968 my parents went there to discuss their sale with the agents, Salter Rex, who had looked after the properties for my grandmother. Their sale was completed in July 1970.

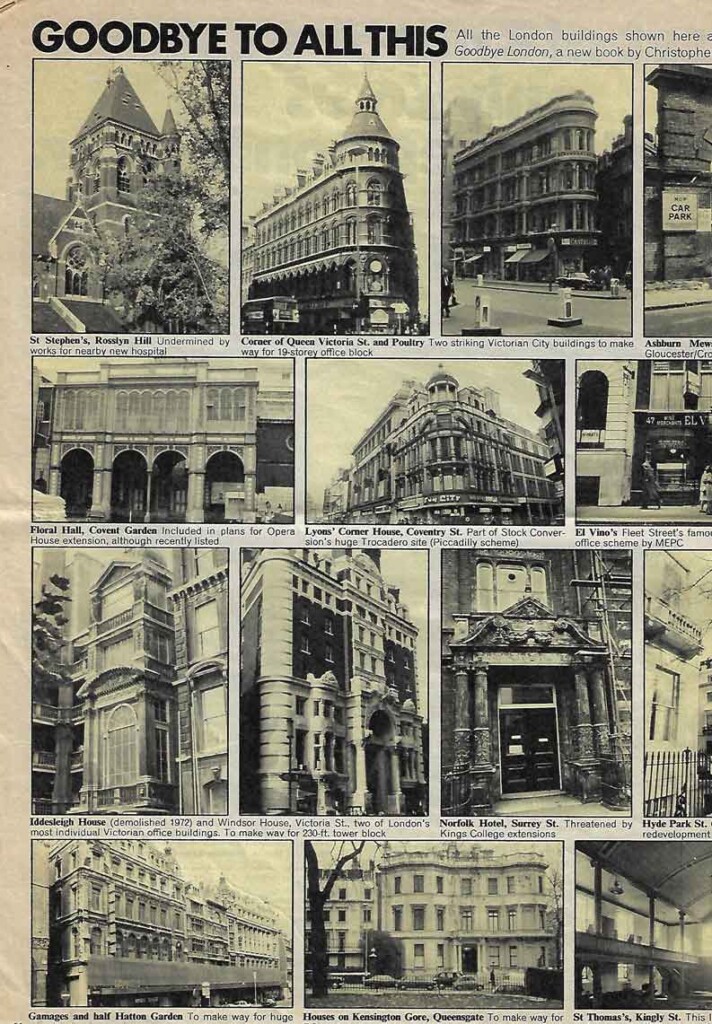

That, as you might say, could have been the end of it but, since a young age, I have had an abiding interest in genealogy. Imagine, therefore, my surprise when, in April 1973, on opening the Sunday Times I was confronted by an article about “Camden’s crumbs from £20m land deal profit” with a follow up article in the Sunday Times colour magazine in May 1973 entitled “Goodbye to All This”. The latter article was about Christopher Booker and Candida Lycett Green’s book “Goodbye London” which dealt with landmark properties that were disappearing under the developers’ demolition ball. Both articles carried shots of Tolmers Square. I determined to learn more about the square and how we came to own some of the properties.

A family chat confirmed my grandmother and her brother had inherited the property from their mother Louisa Cron whose father William Sawyer had, according to the family story, built the square. Could this be true? Apart from being one of my great-great-grandfathers, who exactly was William Sawyer (a name passed down in our family to my grandmother’s brother, William Sawyer Cron and then my father, William Sawyer Gedye) and how had he come to be the builder of Tolmers Square?

My research revealed William Sawyer’s life was a classic Victorian rags to riches story. Born into poverty he spent much of the first three years of his life, along with his elder sister and parents, in and out of the poor house at Newton Ferrers in Devon, but his mother was a resourceful lady who was determined her children should prosper. She apprenticed William and his younger brother Samuel, to her brother, a successful carpenter in Torquay. William learned his trade well. In the 1841 census he was listed as a carpenter, had married Ann Coombe, and had two children. The younger, Jane, died aged three, the elder, Louisa, became my great-grandmother. William stayed true to his vocation and in 1851 was a Torquay furniture broker. Samuel, meanwhile, married Mary Lawrence but let his career take a different tack. In the 1841 and 1951 census returns he was recorded as a carter then a baker. Sometime in the 1850s, both men, accompanied by their families, moved to London. In 1861 William lived at 11 Crescent Terrace, Westminster, Samuel lived at 9 Grafton Terrace, St Pancras. Both were builders by trade, though William sounded the more senior. He was recorded as a master builder.

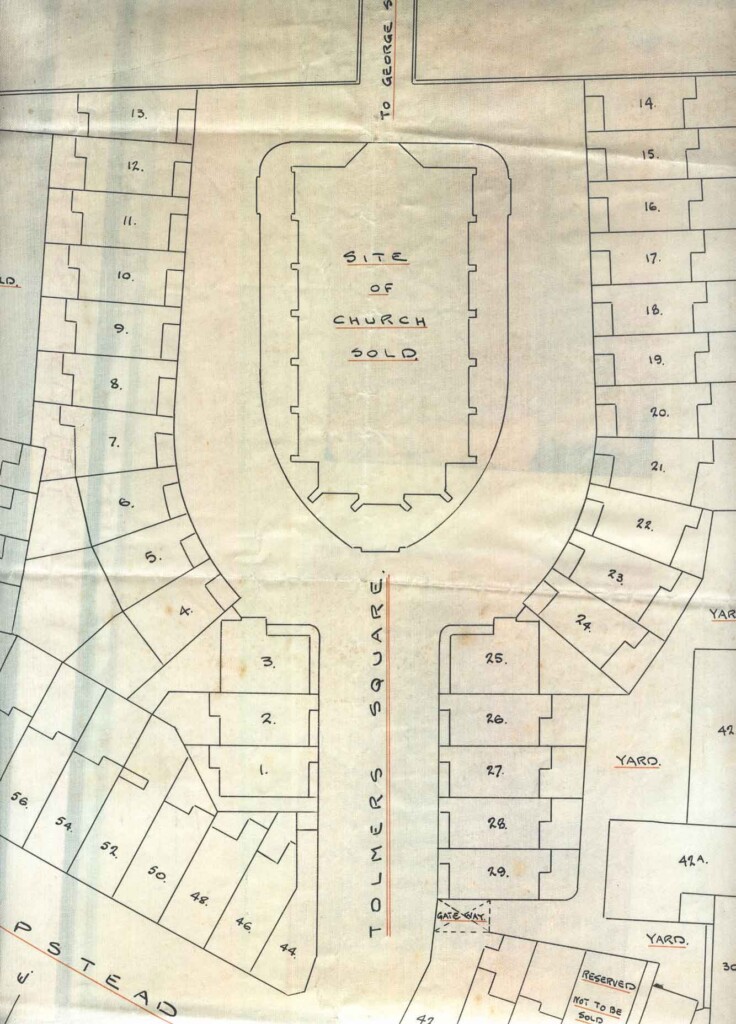

The history of the land that would ultimately become Tolmers Square can be found in ‘The Battle for Tolmers Square’ by Nick Wates, co-editor of this website and a former Tolmers Square squatter. I bought a copy of Nick’s book and was pleased to see on page 215, in a section written by Tim Wilson, that the building of the properties was credited to William Sawyer. But that still left a myriad of unanswered questions. How did William make the leap from carpenter to builder and acquire the right to develop the last piece of undeveloped land at the top of Tottenham Court Road? Was he doing so on his own or was he the lead name in a syndicate of developers and financiers? Were the five properties we owned our share of the enterprise and, if so, who owned the other twenty-four? If anybody can provide answers to these questions I would love to hear from them.

Evidence that William may have been part of a syndicate came from an unlikely source. I was researching the history of one of my grandfather’s sisters and became intrigued by her wealthy employer, William Bennett Daw. He was a Torquay builder, at one time employing thirty-nine men. He also had a brother Charles Daw who was a Torquay builder. WB Daw was married to Mary Taylor, a daughter of Torquay builder Henry Taylor and there were other family connections. Henry Taylor, WB Daw and a local Torquay brewer Henry Adams, all respectable Torquay businessmen, were witnesses to the will of my great-grandfather, John C Gedye, organist of a local Torquay church and a Professor of Music (music teacher). Furthermore, I discovered several of my great aunts and uncles had married into the Daw and Cumming families. Through marriage I was loosely related to the Daws, Taylors, Cummings, all Torquay builders who came to London and built streets of houses, mainly in the Earls Court area. Visit any of the following streets and the property lining Nevern Place, Wetherby Place, De Vere Gardens, Cheniston Gardens, and many, many, more are Daw, Cumming, Taylor constructions. Classic examples of Victorian networking at its best.

More significantly, Charles Daw came to London at around the same time as William Sawyer. In the 1861 census he was in Torquay but, in the 1871 census he was registered as a builder living in Chelsea. The Daws Torquay born cousin, Samuel John Daw, my great-uncle (he married my grandfather’s aunt) also moved to London. In 1871 he was registered as solicitor and ran the Alliance Economic Investment Company which invested client monies in London’s building boom. I also found evidence that William Bennett Daw was a financier of De Vere Gardens which was partly built by his brother Charles. Was Tolmers Square the first venture of these Torquay builders / solicitor who, with its success under their belt, went on to even greater things in the house building boom that was London in the nineteenth century?

An early death from typhoid cut William Sawyer’s life short before Tolmers Square was completed but, from the address given on his death certificate, we know the family had moved from Westminster and occupied number 3 Tolmers Square, the best and most imposing house on the site. What a contrast to being in the poor house in Newton Ferrers. Was living in the best house an indication he was the lead builder? In his will, he charged his wife Ann to continue with his work and to “complete sign and execute all agreements and undertakings entered into by me but not complete at the time of my death”. He also instructed that on Ann’s death his estate should go to Louisa, specifying that no man she should marry should acquire any right to it. In 1863 Louisa married the Reverend George Cron in the newly consecrated Tolmers Square Congregational Church. Their marriage was one of the first marriages registered there. After the wedding the newlyweds set up home in Belfast. Ann, meanwhile, remained at Tolmers Square and supervised the completion of the project. I can only presume her share of the project was to retain the ownership of the five properties that passed down the next three generations.

Ann Sawyer died at number 3 in 1868. She had seen the project through to completion but got little benefit from it. It was Louisa who was the real beneficiary of the rents from her father’s labour. They provided her with a comfortable living for the next forty years. On her death, in 1909 Louisa divided her estate among her four surviving children but, as her will made no specific reference to the properties, I don’t know if the five that were inherited by the two youngest Cron children were the only properties Louisa owned. My inquiries within the family have drawn a blank as to whether either of the two elder siblings also inherited property in the square. They may have been pleased if they didn’t. The properties came with a problem.

Rents were non-reviewable and could only change when tenants left and new tenants took up residence. Tenants on cheap rents had no reason to want to move out and the landlord faced rising maintenance costs on a level income. As time passed, my grandmother found she had bills for compulsory repairs that exceeded the rent she received. Tolmers Square may have survived the blitz but it couldn’t survive neglect and my grandparents struggled to survive it draining away their savings. The area became shabby. Tenants muttered about absentee landlords (two widows in their 80s who lived in Newcastle and Whitley Bay with at least one Tolmers Square tenant adding to their woes by refusing to pay rent until repairs were carried out).

It was no surprise then that, when my father and his sister inherited the problem, they were keen sellers. But there were other reasons for being keen sellers. I don’t want to repeat what can be learned from reading Nick’s book, but we were also victims of the development company Stock Conversion’s policy.

Nick’s’ comments on the piecemeal purchase of properties by Stock Conversion in the streets surrounding Tolmers Square and in the square itself make interesting reading. I quote – “Stock Conversion’s main objective was to buy up property as cheaply as possible. Secrecy was essential. The owners had to remain unaware of the future potential of the area otherwise the prices would soar. Rundown properties could then be bought for a mere fraction of the potential land value on which they stood. For instance in 1962 they bought six freehold houses in North Gower Street for £17,000. Ten years later the land on which these houses stand was worth £150,000. In 1969 (it was actually July 1970 before our sale was completed) it is rumoured that five houses in the Square itself (correct – three for my father and his sister and two for their aunt) were sold for £17,000 (actually £19,166 for the five) when at that time the land on which they stood was worth £70,000”. There was nothing illegal about the way that Stock Conversion bought up land, they were merely persistent … [and patient].

Stock Conversion’s policy was simple. Having bought the property, they did nothing to it. It became more dilapidated, tenants moved out, buildings collapsed, values in the area crashed, and did we want to own five terraced properties in the middle of a demolished building site? Were we robbed by Stock Conversion? If we had held out, could we have extracted a higher price from them? You have to see it from all sides.

My father, his sister, and their elderly aunt owned five properties, some with compulsory repair orders on them, hundreds of miles away from where they lived. The properties were occupied by tenants, at least one of whom refused to pay their rent, in an area where Stock Conversion had been buying up property over the past eight years and so controlled a lot of the area. Stock Conversion had already boarded up many of their properties, adding to the derelict and run-down air that pervaded the area. Property in neighbouring streets would eventually collapse through neglect and Stock Conversion could sit it out for far longer than we were prepared to. Our aunt was eighty-two, with no direct heirs and not interested in a fight. My father and his sister shared the ownership of their three properties and wanted to extract their value so that they could receive the cash value of their inheritance. A further complication was that my father was heading to Zambia to work, so wouldn’t be around to conduct a fight. It was a case of all sell or none sell. As nobody wanted to stand their ground, the no-sell approach wasn’t an option when there was a buyer willing to take the problem off their hands.

Here I take my hat off to the squatters and residents of Tolmers Square. When the battle was going on I lived in Oxfordshire and had no idea of the significant role Tolmers Square was playing in the housing versus offices battle. Thanks to the “battle”, the skyscrapers that were the dream of Stock Conversion, were never built and they were forced to sell the land to Camden Council for housing development. Today, Tolmers Square, an oasis of peace and quiet, consists of council flats set around a traffic free area of grass and trees that cover the area where the church once stood. The brick-built properties may not have the grandeur that William Sawyer envisaged and achieved, though his building was somewhat marred by the domineering church in the centre of his square. Perhaps if there had been a park in the centre of Sawyer’s square, rather than a church, the area may have survived in its original form. On the plus side, the area is still used as my great-great-grandfather intended, housing for Londoners. The battle for Tolmers Square was a win. It is still called home by those who live there.