In conversation with Patrick Allen

Patrick: So Jamie gave you the signal. He said ‘I’ve found somewhere, you must come and join me.’

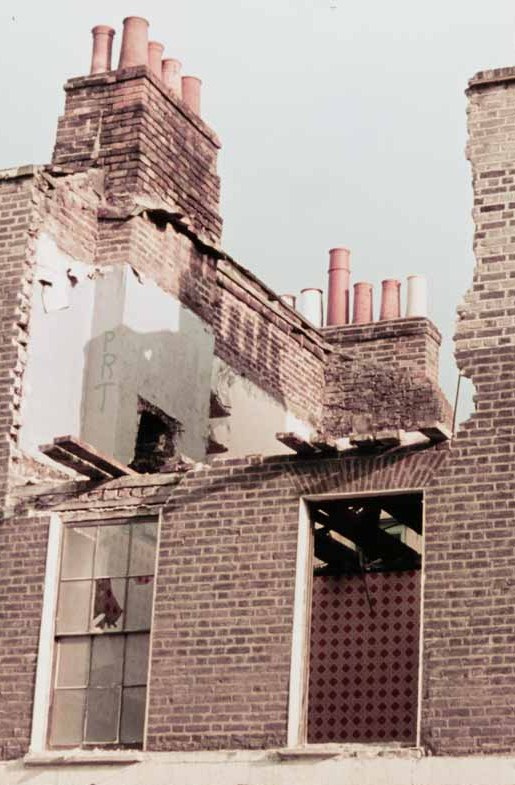

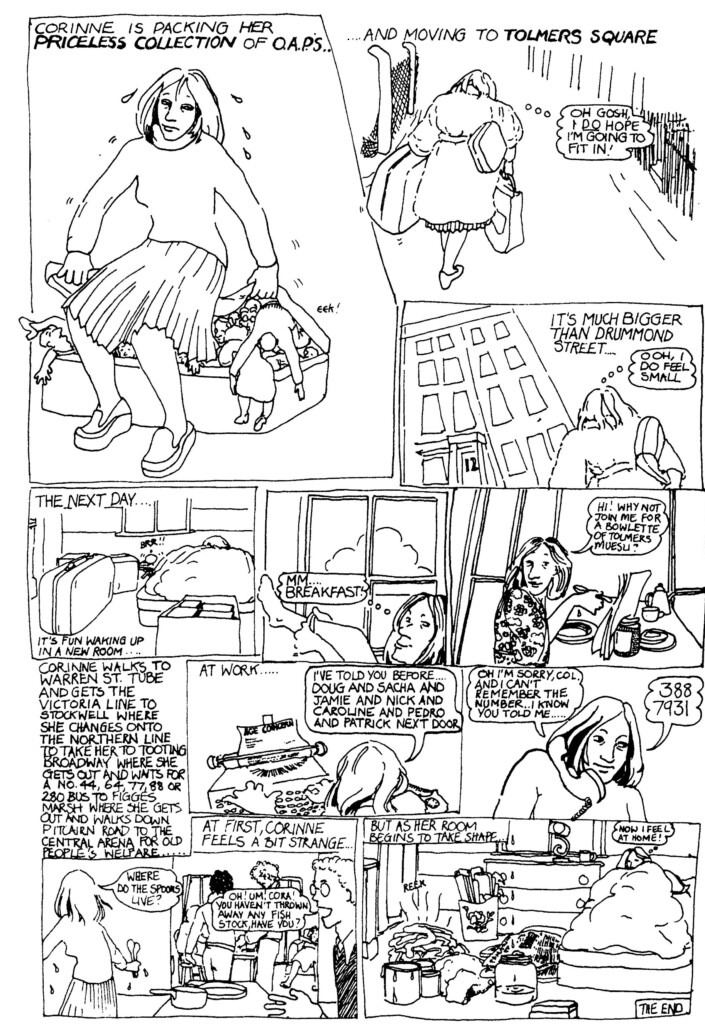

Corinne: He said ‘Oh yeah, by the way we’ll be squatting’, and I went ‘oh yeah, that sounds really great’. I thought we’d be doing a ‘good thing’ [occupying houses slated for demolition, whose tenants had been forced to leave in order to make way for unwanted offices]. Jamie was a friend I’d met in Oxford; by October 1973 I had a 9–5 job at Age Concern in nearby Gower Street. We’d planned to live together when he came to London, but I’d never actually met Sacha until we were all outside 117 Drummond Street. We all had the reaction ‘what a gorgeous place to live’. It was a beautiful, very dilapidated, Georgian house, which smelled of cooking from the Indian restaurant. I loved it. The gas lamp fittings were still there, although they didn’t work. My room was on the top floor at the back, which I painted eau de nil and pink.

Patrick: When you moved in there wasn’t any water?

Corinne:

We discovered an outside toilet in our back yard, and once you lot next door at 119 connected the water both households each had a flushing toilet. Before that, Jeyant Patel, who owned the restaurant next door, allowed us to use his outside loo with its big fat slugs. (There was always that thing between 117 and 119; 117 was dependent on the technical skills at 119, like getting the water and electricity rigged up, but Sacha had the social skills with Jeyant and others who helped us move in). Even with running water, I’d wash at the house but once a week pay for a nice, quiet bath at Euston station. My family was in London, so I had plenty of alternatives for washing, I was more privileged than some. My sister, after visiting me when I first moved in, returned home in tears, telling my parents how awful it was. We had a tiny kitchen, and a sitting room with a range and grate. And we had wallpaper. Jamie insisted on going to Colefax and Fowler for the wallpaper:, a very smart lattice design, in the style of his parents’ house in Lewes. When Celia and Orlando (Jamie’s younger brother) moved to a squat in nearby Warren Street, he papered the whole of the house with music sheets. That looked very stylish too. Everything happened in our living room; food, parties, visitors. John Craddock, Sacha’s father, came with piles of coal for the fire.

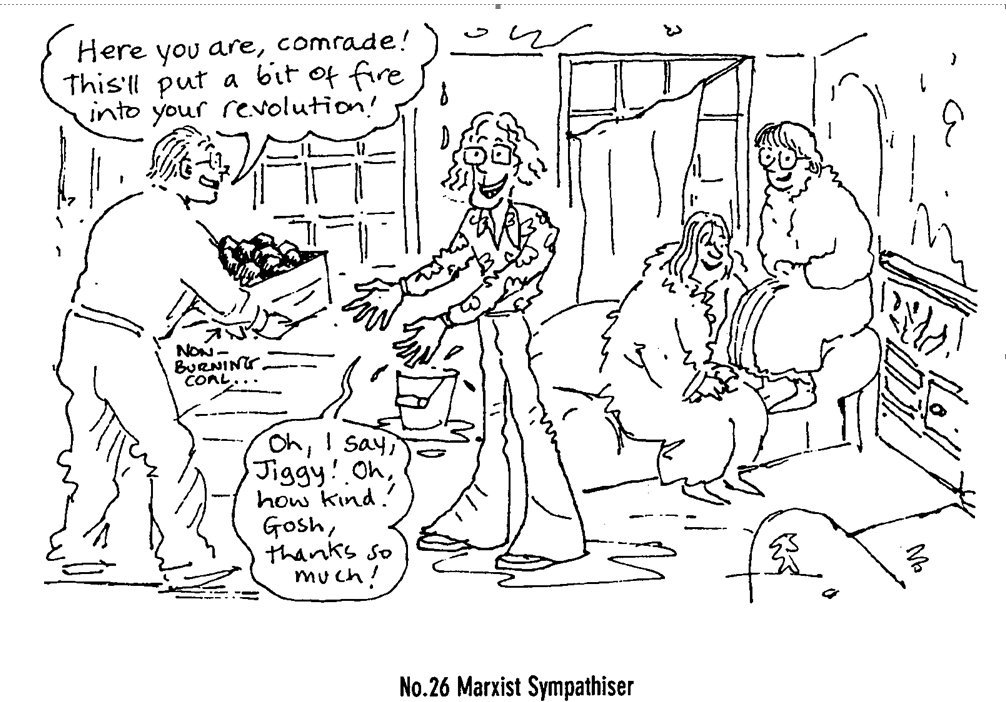

Sacha and Jamie were members of the IMG (the International Marxist Group). It was just something that they did in the same way that I went to work at Age Concern. I was quite a bourgeois person and just went off every day to do my job, but I do recall the odd night’s surveillance for Action-Backed Inquiry into Property Development, to prevent another empty house from being demolished. By 1976, 117 Drummond Street was due for demolition, so we moved to Tolmers Square. That’s when I left Age Concern to become a freelance illustrator and designer.

Patrick: So 12 Tolmers Square turned out to be a very long and stable set up from about 1976 to 1979? It became the replacement for 117 Drummond Street with more expensive wallpaper.

Corinne: Absolutely, again from Colefax and Fowler.

Patrick: This was obviously a requirement – that wherever Jamie moved there had to be expensive wallpaper.

Corinne: I still have this recurring dream about the rickety stairs. I had a big room at the top of the house. When I tried to go downstairs to the loo, I’d see that many of the stairs were missing. You set up a shower at number 11, and we would trot along the balcony and go and use it.

Patrick: Yes it was pretty fancy, with a Sadia two gallon water tank, mosaic tiles on two sides, a shower curtain on the other sides. The tiles were provided by Chris Weller’s mother.

Corinne: I still resent your taking a piece of wood that I had been hoarding. You said ‘oh that’s perfect for my shower’.

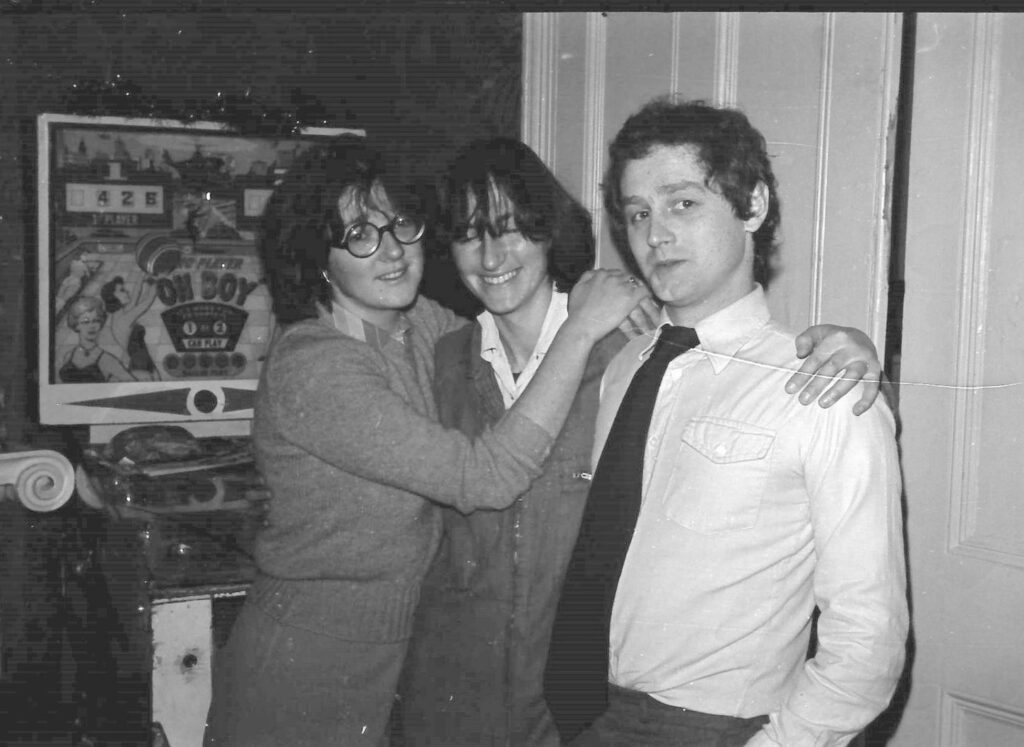

Patrick: So number 12, like number 117, became the big social centre for meals and parties.

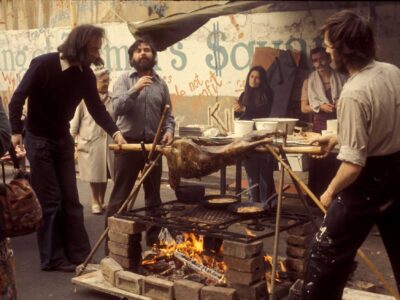

Corinne: Yes, very much so, it also became the social centre for the IMG lesbian and gay caucus. Jamie would cook for the comrades and then leave the house before they arrived. Our cooking at no 12 was massively enhanced by buying huge pans, cauldrons, suet pudding holders and fish kettles from British Rail when they cleared out their warehouse nearby. Perfect for Pedro and Sonia’s elaborate Brazilian feijoada, one of our favourite meals. It took all day to cook, and we had to go off to Camden Town to buy pigs’ tails, pig head and trotters.

Patrick: And rather good chopped up spring greens, I think, and chili. It involved strange pig things as well as beans of different kinds. All the catering pots came into good use at the Christmas banquet because we cooked four turkeys in four different houses and vats of frozen peas. It was an epic occasion and the planning was incredible. I remember buying the wine, turkeys, cooking the peas, setting up the tables.

Corinne: That was certainly one of my highlights. It was such fun, as long as you weren’t a poor guest. We tried to heat up the place but it was absolutely freezing. Guests stuck at the tables at the far end with no heating had to wait hours and hours. Of course, we were so busy cooking, we had an absolutely brilliant time.

Patrick: I remember stirring a vat of frozen peas on the other side of the square thinking when are they going to come to the boil? Frozen peas were supposed to be a quick option.

Corinne: Our friends Ana and Patrick moved in to the basement of number 12, after they were evicted from the south side of the square. One morning an electricity inspector came to read the meter, which was in their room. Of course, it was ghastly and dark down there. Ana opened the door in her dressing gown and asked ‘Who are you?’ in a very hostile manner. The inspector replied ‘I’ve come to read the meter. Why, are you poorly?’ And Ana replied: ‘No, I’m not fucking Pauly, I’m Ana!’ [OK, you had to be there at the time, but this sustained us for years.]

Patrick: So, what does it mean looking back on it? Did it affect the rest of your life?

Corinne: Yes, it seemed like the right way to live. It felt very comfortable for me, living with a lot of people. I’m still partly living communally at Great Russell Street after all these years.

Patrick: What is uncanny is that the house you moved to in Great Russell Street is much the same as 12 Tolmers Square in many respects. It’s a big house with a lot of communal eating, a little bit messy, rather cold, but a constant stream of parties and meals and events and a lot going on.

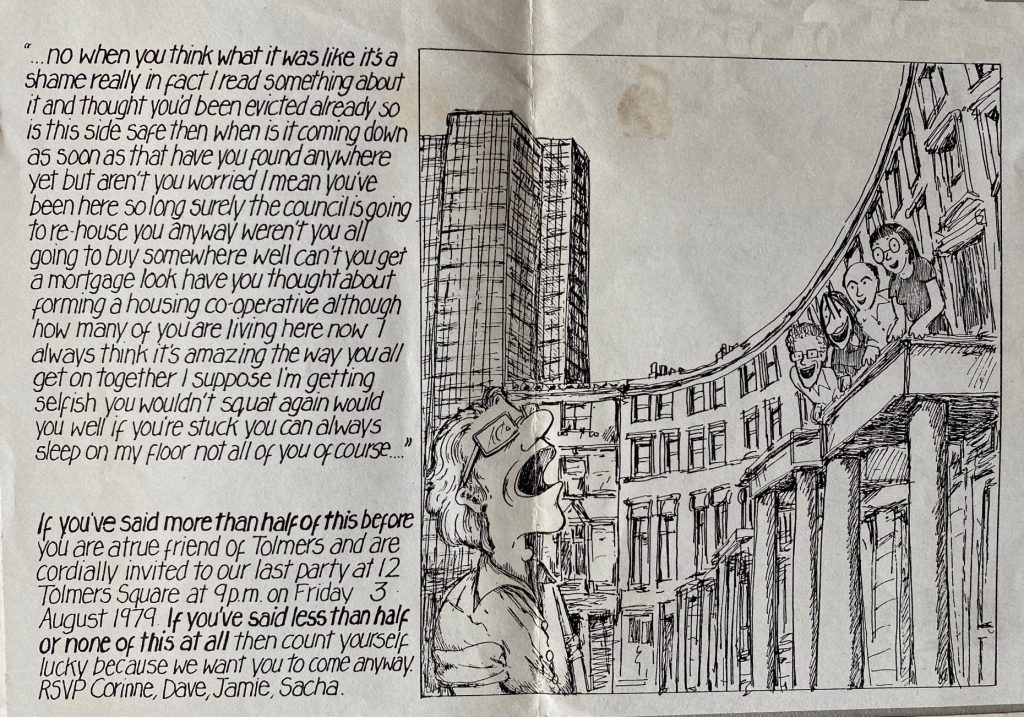

Corinne: For me that seems like the right way to live. But you have to have somewhere that’s large enough to be able to take it. When we won our campaign to get rehoused by Camden Council (thanks very much, Ken Livingstone) in 1979, we found ourselves in three-bedroomed flats, with a kitchen and a sitting room – but usually somebody sleeping in the sitting room – and it wasn’t enough. Our flat was at Blashford, Adelaide Road. There were three or four of us, so you’re back to that rigid flatmate thing. With a larger group of people and a house to accommodate it you can have your own space and then be communally together when you want to be. Your comings and goings don’t need to be announced. That makes an enormous difference. Squatting allowed that.

Patrick: So you only had a few months in Blashford before the house in Great Russell Street came along?

Corinne: We actively started looking for somewhere else because we knew Blashford wasn’t right. We had to find a big enough house. Obviously, living together is about people who you have relationships with. I’ve always had a partner elsewhere, somewhere else to go to and spend my time. For the past 30 years I’ve been living in Brighton with Martin as well as at Gt Russell Street. But I never remember thinking that I wanted to live in another way. Having my cake and eating it, socially.

Patrick: Well there is always something going on isn’t there? There is always somebody arriving, somebody leaving, staying temporarily.

Corinne: Yes, and that’s exciting, you welcome it because it’s a ready-made activity. Sacha and I have been partly living together for what will be 50 years in 2023. I feel I’ve benefited from that too. Her philosophy is that as long as you’ve got enough red wine, everything is do-able (only nowadays it has to be decent red wine!). It’s actually that kind of friendship network which is the most important thing to me. I always had a strong sense from a very early age that my friends kept me sane, just really enjoying my friends and having that wider network outside of the family for support. So if you can incorporate that in the way you live, so much the better.

Patrick: What made it so special in Tolmers was the opportunity to create an entire community with unlimited space. Also it was safe because it was within the confines of the Euston Road and the station – a quiet, self-contained community. I think we have to admit that we were lucky too. It was quite a benign time politically, compared to where the country is now. Squatting was permitted or at least tolerated, we could get the electricity connected, we were never harassed by the police or anybody. We had access to all this empty property to use for our needs in the middle of central London, quite incredible.

Corinne: I was very lucky in that I was able to benefit from being part of a whole group of people who shared their skills and efforts. It’s like engineering a situation where you are living in the way you want to, but it’s definitely thanks to others that that is able to happen. I think that’s true whether it’s somebody who knows how to fix up a water tank or somebody who knows about the political situation. It wouldn’t have happened if that group of students at the Bartlett School of Architecture and Planning had not been doing a study of the area and found a way to take action. Jamie was the key person for us who did that. It is interesting how Jamie’s ethos, politically or decoration wise, reflected the politics that he had and also the style ideas for these spaces and how they should look. We all brought a bit of that in. I think you and I came from more suburban backgrounds. You had a very strong sense of all the mod cons that one needed to enjoy one’s life. I think I was much more sloppy than you and was just happy to be able to find a solution. I didn’t actually meet Sacha before we’d already been betrothed via Jamie to go and share a house. We met because we were going to live together. It’s extraordinary because it’s been a bit like an arranged marriage lasting over 50 years.

Patrick: I arrived in London in 1973 then I met somebody who was squatting and I got very interested in the whole squatting idea; it sounded exciting. I was paying rent and I needed to save money because I was going to go to the College of Law and wasn’t going to get a grant. Also squatting sounded like an entrée into something happening politically which ticked my box of wanting to be involved in radical things. I made a few enquiries and Tolmers Square came up on the list. I set off one afternoon in the car and I drove into Tolmers Square for a recce.

Corinne: I love the idea of your finding a place to squat in Central London by driving there in your car. At that time you wouldn’t be allowed to arrive at a youth hostel in a car! I once painted a slogan on the wall of number 12 ‘This house is full of bourgeois fuckers’, but you know, some of us were: there were a lot of us from privileged backgrounds, who could choose to live like this and we were able to do it, because we had support from friends and family. Squatting enabled me to give up my job in order to start up a career as a freelance illustrator. It was very important to not to have rent to pay in order to do that.

Patrick: Squatting enabled me to go to the College of Law. This was only possible because I had no overheads and was living on carrots and onions. And we brought in many of our friends to join us.

Corinne: Yes, Peter Cross was a friend of friends from Sussex University. Sacha brought Simon Howard, Dave Taylor, Becca, all studying at the Oxford College of Further Education. Jamie introduced people like Rod, who was already living in Tolmers Square. Experiments in communal living as opposed to communal loving.

Patrick: Well, we did that too.

Read more about the author Corinne Pearlman

More stories

No shame

by Tim Davies

A squat. I didn’t even know what that meant. I had to look it up – in the days before Google. Encyclopaedia Brittanica in those days.

Rebirth through fire

by Alex Smith

I liked the dynamics of Tolmers Square. I was now on the South side where we were eccentric and unconventional, a bit wacky.

The legal battle

by Patrick Allen

Outside the court there was relief and jubilation for the squatters but consternation for the property company and their lawyers.

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.

Traveller’s tale

by Rod Smith

Instead I went on a ‘teaching English as a foreign language ‘ course so I could travel the world.

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.