As told to Patrick Allen in 2021

In 1973 I was living in Finsbury Park with my girlfriend Celia Potterton. I was a medical student. I had finished my first degree at Oxford in 1972 and was now studying for the post-graduate 2nd MB at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield. Our bedsit accommodation was very unsatisfactory, and we were about to move out as it was nearing the end of the rental. I knew some people who were squatting, and I had been down to York Square, East London to check out a potential squat there, but this did not work out.

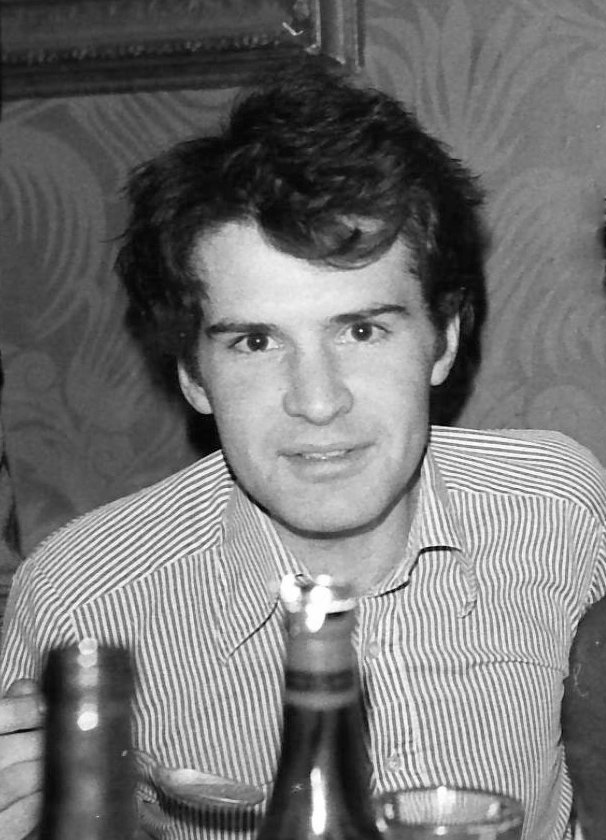

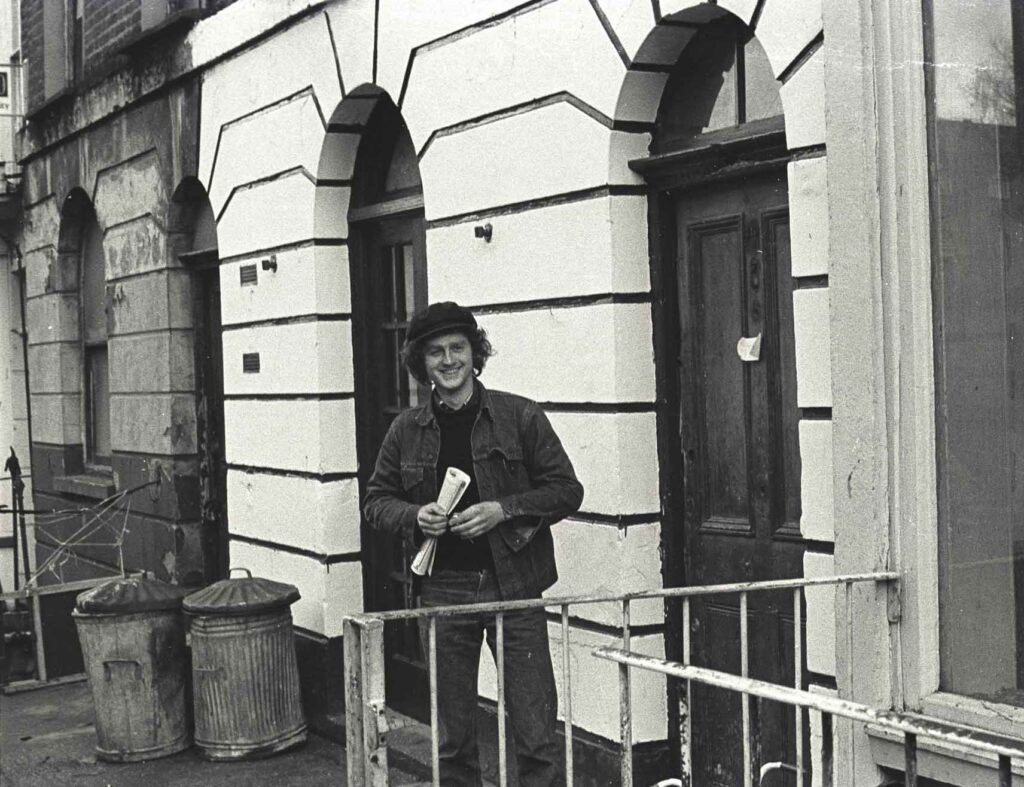

Then Patrick Allen, a friend from my college in Oxford, called me up. He said he had found a house to squat in Drummond Street, NW1, and wondered if I would like to join him. I was delighted to accept the invitation and the following weekend we set off in Patrick’s car, the Hillman Super Minx, to Drummond Street with a mattress on the roof, a lock and some tools. The front door of 119 Drummond Street was swinging open, so it was a simple job to walk in and then fit a lock, whereupon it would be ours.

Patrick then went off for more supplies and I was sitting on the stairs waiting for his return when the front door opened and in walked Barry Brookshaw, who I had not met before. He said “what are you doing here?” I said “I am just moving in to squat the house” and he said “I have been chasing it myself for a little while”. So I said, “well there’s plenty of room, when Patrick comes back we’ll sort it all out”.

Shortly afterwards Patrick returned, and we secured the front door with the Yale lock. We wandered around the house and looked for the water and electricity, and decided where everybody was going to be. Barry took the ground floor, Patrick the first floor front room and I was on the top floor at the back.

There were a number of immediate jobs to be done such as stopping the roof leaking and getting the water and electricity going which we did over the next week. We went onto the roof, patched it up with felt and tar and moved the tiles around a bit.

Barry made a trip to Woolworths in Camden Town to get plugs, sockets and wire, and I think he did the rewiring and some of the plumbing. We got the electricity connected by the London Electricity Board pretty quickly, and fairly soon we had water connected to our kitchen on the first floor at the back, and to the outside toilet in the back garden. There was an ongoing leak in the water supply to the lavatory, so Barry improvised brilliantly with an old tin bath which caught the leak and diverted it into an existing drain. He put some fish in the bath.

Next door at 117 they didn’t have a drain, so they collected all their slops in a tin bath – every now and then the window was opened, and they would empty it into their back yard. This was always fun to watch.

Patrick was the driving force behind the painting of the front of the house. I realised that this was a really good idea because we made the house look smart and quite respectable, and that reinforced our possession, our existence. There had been a lot of rubbish out the front and we tidied it all up and made it look nice.

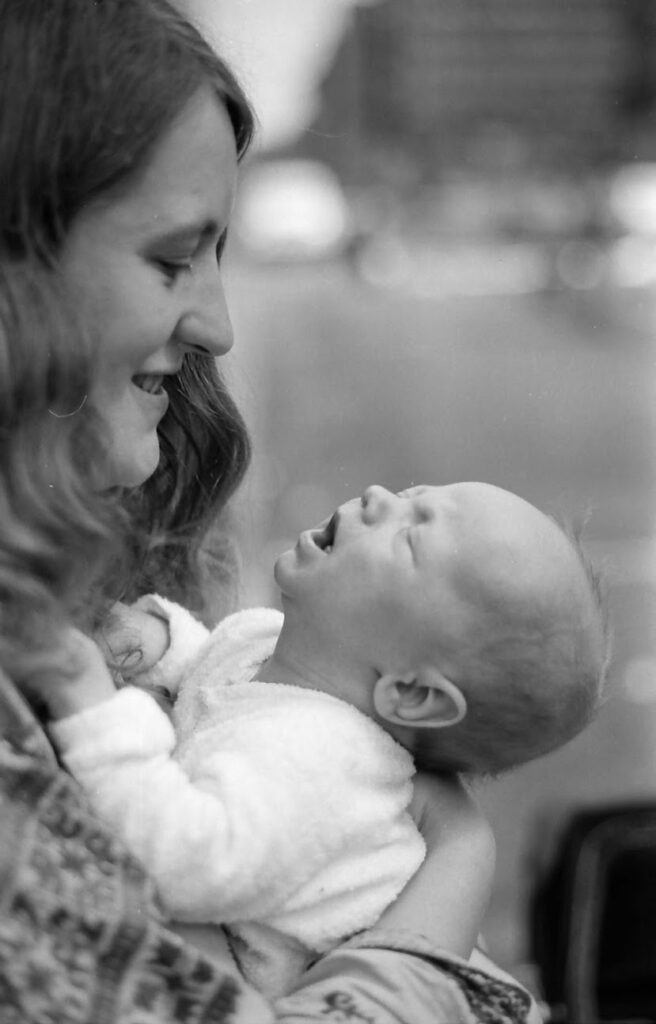

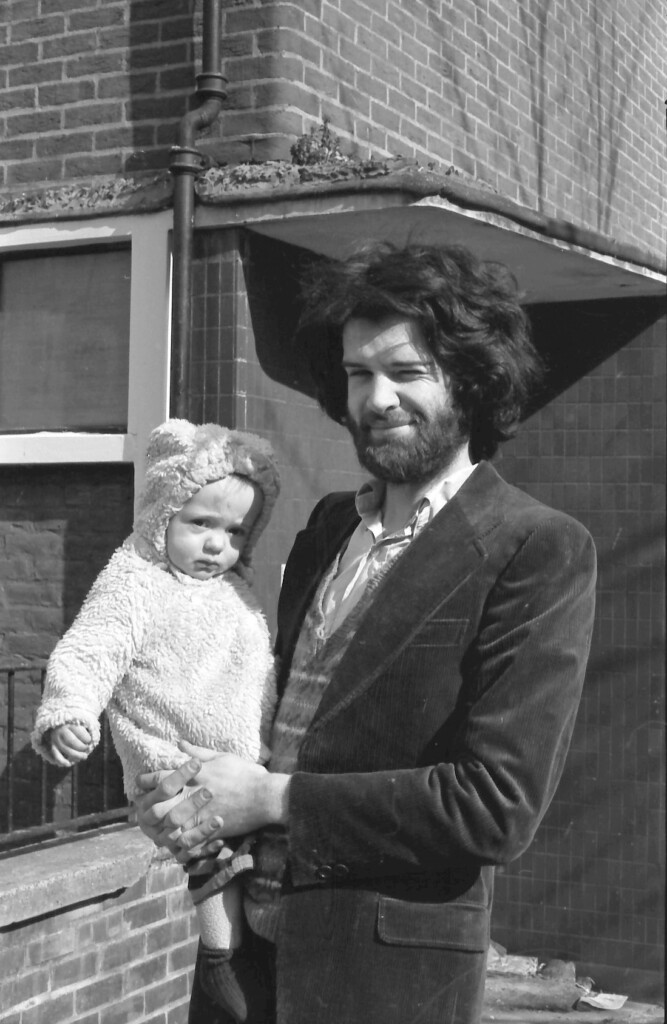

Celia who was pregnant moved in, and Jesse was born in May 1974. They were on the top floor. I needed an electric geyser for the kitchen so we could have hot water. Jesse was born in the Whittington Hospital. There was a junk shop that I passed on my way to the hospital which had a geyser on the pavement which was exactly what I wanted. I bought it, stuck it on the wall in 119 Drummond Street and connected it. By the time Jesse came home from hospital we had a hot water supply.

I used to go to University College Hospital (UCH) for baths. You could go to Euston Station, but you had to pay 50 pence. There were some free bathrooms in the student union of UCH in Gower Street. I would go in the back way through the fire escape (with a bathplug).

Otherwise, I would go to Kentish Town public baths. But the thing with the public baths is that you get a fixed dose of hot water. The hot tap doesn’t work. You pay your money, then the attendant comes in and gives you a shot of hot water in the bath which is completely scalding. Then you put in the cold water and just the right amount because obviously you want to lie in the bath as long as possible without the water getting too cold.

Once I was lying in the bath at Kentish Town. I had stuck my watch up on the wall with a bit of blu-tac. Suddenly there was a crash and my watch fell from the blu-tac and shattered on the floor….

I got a job in the Mobil garage on Hampstead Road selling petrol. I was the night staff so I used to start at 8 pm and would finish at 7 o’clock in the morning. The job was not too busy so I could often sleep or do some academic work. I would come home, have more sleep then go to the hospital at midday then come back and go to the garage.

After two years we moved out of Drummond Street because we were told that they were going to redevelop it earlier than other houses and we all had to make other arrangements.

I opened up a house at 229 North Gower Street, which was in immaculate condition. I knew that it was becoming vacant and so I got in over the roof from another squat.

I dropped in, nipped downstairs and slipped a new lock on the front door – and there we were. It had running water and electricity, and it was all sound, but there wasn’t a bathroom there either. Celia moved in and she and Jesse were on the ground floor. There wasn’t much in the way of yard space. I was up on the top again, at the back.

I put gas into the kitchen, and a cooker and a sink. This was a busy time as I was working at the garage, appearing in the hospital and fitting out the house.

I moved to 12 Tolmers Square in 1976 where I stayed until the end in 1979. I moved in with Sacha on the first floor of number 12. Pedro and Sonia were on the ground floor and Patrick was next door. Dave Taylor was downstairs at the back. Cora upstairs at the front and Jamie in the basement.

The best thing about living in the Tolmers community was that it showed you what could be done, how you could put your mind to it and make things work. It showed you how you could work with people.

The food coop is a good example. Barry Brookshaw was a stalwart of the food co-op because he drove a van. Patrick also drove us in the Super Minx.

We used to buy bent cucumbers which were very cheap as supermarkets didn’t want them. We were buying a box of bent cucumbers and the guy needed a name for the invoice. He said “what’s your name then, oh I’ll put it down as ‘Whiskers’. This is because Barry Brookshaw had one of his intermittent beards. From then on whenever we had to volunteer a name, we were Whiskers.

Back at Drummond Street, Oli’s mum Debby Banham used to help with all the bookkeeping of the food coop and the splitting up. Then we’d put it all out to sell.

Squatting was undoubtedly a formative experience. Was it enjoyable? Well, yes. If you were going to be having a hard time it was a good place to have a hard time in and it was brilliant to be without landlords.

In our previous bedsit the landlord would turn up on a Saturday morning and come into our room saying he’d come to check the meter. So getting away from all that and having control of things was marvellous. Perhaps we didn’t pay enough attention to it at the time. We didn’t know how lucky we were in that regard.

For example, my young brother Hamish came to stay for half term in Drummond Street. I remember he redecorated all the hallways. I gave him a pen and said if you want to draw your pictures, draw them anywhere you like, and he decorated the whole stairwell with all sorts of pictures that he liked.

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it, but then when we moved in to Drummond Street, there were five or six sources of sheet glass a bus ride away. You didn’t need a car or anything, you could go and collect them. Its not the same now. Lots of jobs are quite difficult to finish because you can’t get the stuff.

I met many Tolmers friends recently at Barry Shaw’s funeral. I was glad to see them and we slipped into effortless communication, I felt uplifted by their presence.

Did squatting change my life in some way? Yes. I’m not sure what I would have done to sort out the shortage of money. I didn’t have a grant because my father was bad at filling in forms and the Scottish Education Department which paid my grant had a policy of being difficult with people who went to foreign universities, i.e. in England. As a result I didn’t get a grant until I re-registered as a mature student. So if I hadn’t gone to Tolmers, heaven knows what would have happened. Maybe my parents would have paid something or I may have got some sort of job or I may have given it all up. Looking back squatting was critical to getting me through my medical studies.

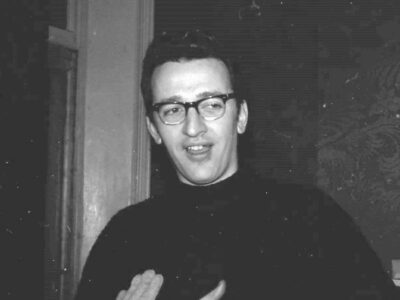

Colin Ferguson January 2021

As told to Patrick Allen

Read more about the author Colin Ferguson

More stories

Afterlife

by Alison Ravetz

It's wonderful to know that all that work and struggle are not relegated to a museum of good ideas, but are still being carried forward.

American architecture student

by George B Bryant

My living conditions were primitive but there was electricity, water and mail delivery. I don’t know what I would have done had I not been able to live there.

The legal battle

by Patrick Allen

Outside the court there was relief and jubilation for the squatters but consternation for the property company and their lawyers.

Ahead of the game

by Orlando Gough

I am twenty-one and I’ve lived a privileged, you could say molly-coddled middle-class life. I have been to London before but I’ve never lived there. And here I am, right in the thick of it,...

Wait until the head teacher sees this

by Oscar Gregan

I skimmed though the paper looking for the photo. I could not find it! I was just about to return the paper when I noticed the front page.

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.