In June 1972 I finished my studies at university. I had decided to qualify as a solicitor and booked a place at the College of Law, Lancaster Gate, London for January 1974 to study for the Law Society exams. This gave me time to travel so in February 1973 I set off to the USA for six months, aiming for San Francisco in the hope of attending many Grateful Dead concerts (successful!).

In September 1973 I returned to England to start a new life in London and in readiness to take up my law studies. One of my friends from university was setting up a house in Kentish Town and invited me to move in and share the rent.

I looked for work to support myself and pay for the law course. First I drove a van for University College Hospital in Gower Street, delivering food supplies around various hospital sites in North London. Then I found a job on a building site in Debden, Essex where I met Grant Lilley who became a good friend. Grant lived in a squat in Woodsome Road, Parliament Hill and we shared the long drive to the building site each day. With my first wages I bought a sturdy second hand Hillman Super Minx for £100 and a Pentax Spotmatic camera as I was a keen photographer and developed my own film and prints.

I enrolled in yoga and chamber music classes at Parliament Hill School where I played the flute. So life was busy but after a few weeks I decided that renting a room in Kentish Town was not quite right. I wanted new horizons and adventure and to discover more of London life and politics. I also wanted somewhere cheaper to live as I needed to save money for my law course.

Squatting was a big thing in North London at that time and was constantly in the news in magazines like Time Out which covered London politics and housing issues. North London had many streets of houses boarded up with corrugated iron – terraced houses awaiting demolition and redevelopment for local authorities. At the same time there was a shortage of housing, especially for young single people. Local authority housing was not available to them and there was almost no private rental market. I decided that moving to a squat was the solution to a number of issues – it was political and sounded exciting, would provide a cheap place for me to live during my law studies and new friends and interests.

There were a number of options and I made enquiries. There were empty houses everywhere – Kentish Town, Holloway, North Kensington. Then I heard about Tolmers Square which was off the Hampstead Road between Euston station and Warren Street.

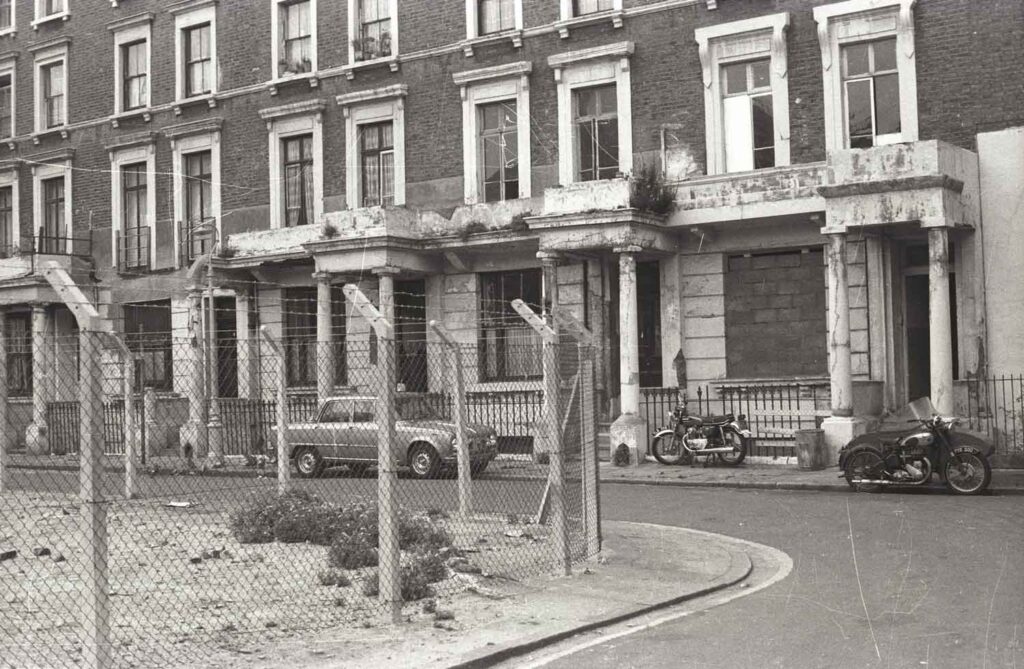

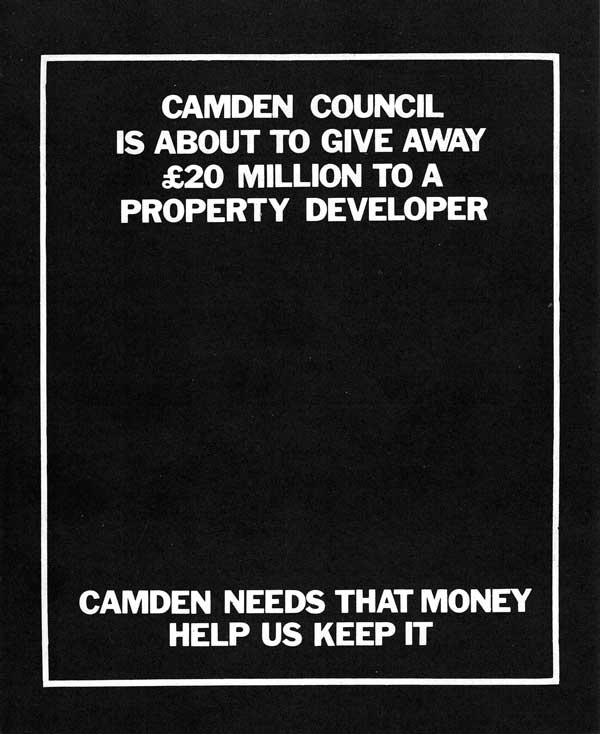

Tolmers was a large, horseshoe shaped square of grand houses built in the 1860s with porticos and balconies. It had been blighted by planning and redevelopment delays. Many houses had been unoccupied for years and were in a very poor state with broken and boarded up windows. The balconies were crumbling and on some houses had fallen down or been removed. I later learned that most of the square had been bought up covertly by Joe Levy and his company Stock Conversion Ltd. Joe Levy was a property developer who had made his fortune developing bomb sites after the war. His company had been responsible for building the massive and unsightly Euston Tower (his greatest achievement) which overlooked Tolmers Square on the corner of the Euston Road and Hampstead Road. Apparently he wanted to knock down Tolmers Square and build another tower. For this he needed planning permission from Camden Council, then led by Frank Dobson.

Stock Conversion hoped that Camden would be persuaded to grant planning permission in return for including some social housing in their scheme. But local residents, politicians and journalists were up in arms about this plan which featured often in Private Eye.

I decided to check it out and drove to Tolmers Square one afternoon where I met one of the squatters, Ches Chesney. Several houses were squatted in the Square and I asked Ches if any were available. He said that I should try Drummond Street around the corner and speak to Sacha Craddock who lived there. I found Sacha at 117 Drummond Street. She had moved in a few weeks before with her friend Jamie Gough. We chatted and it was apparent that the house next door to her, 119 Drummond Street, was empty. She explained that she and Jamie had been moving into 119 but rejected it when they saw the state of the brickwork on the back wall which looked dangerous. She also said that the house was bagged by a friend of hers, Rod, who would be moving into it shortly.

The house looked fine to me. Some bricks had fallen off the top of the back wall due to faulty guttering but I thought we could fix that. It was an 1850s terraced house of classic design on four floors with some broken windows and a sheet of corrugated iron loosely attached to the front door which was open. The front rendering had some graffiti and badly needed some paint. This terrace of three houses had apparently been bought by London Transport at the time of the construction of the Victoria underground line but had lain empty for 20 years.

I felt it wasn’t possible to bag a house indefinitely so I told Sacha that I would be moving into 119 at the weekend with my friend Colin Ferguson and that Rod was welcome to join us if he was around. (Rod Smith who was living in Oxford at this time eventually came to live at 12 Tolmers Square in 1976. He was an accomplished pianist and we later played flute and piano sonatas together, sometimes at the Fenton House harpsichord collection in Hampstead.)

I spoke to Colin who had been at college with me. He was keen to move in to Drummond Street. He said that his girlfriend Celia would like to come too and she was pregnant so we would have a busy house. This was all agreed and we made plans to move in.

On the following Saturday morning, Colin and I drove to 119 Drummond Street in the Super Minx with a mattress on the roof rack, some clothes and tools. We removed the remaining corrugated iron from the door and put on a new Yale lock. We put the mattress in the first floor front room which was to be my bedroom / study. We were now in possession!

At this moment another prospective squatter arrived – Barry Brookshaw. He was friendly and explained that he had planned to move into number 119 as well but we had got there first by one hour. We said there was plenty of room and he was welcome to join us. He decided to take the ground floor double room and immediately set about clearing the rubbish inside.

Barry had a strong Australian accent but we learned he was from Essex and had acquired the accent as a result of living in a house with Australians. Barry turned out to be the perfect house sharer as he was extremely practical and capable of any DIY. Such skills were essential to make the house a success.

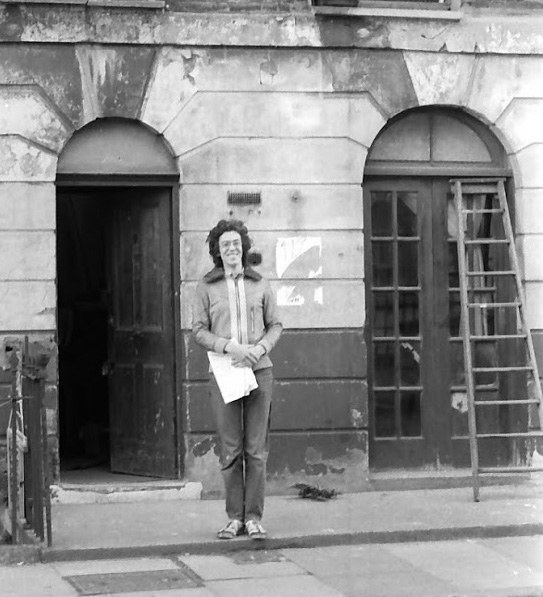

I took several photos of the house on the first day and of Sacha, Jamie and Jeyant Patel who owned the Diwana restaurant next door at number 121. I set about re-glazing several broken windows in my front room.

The bad news was that that the house had no water supply. Sacha explained that the water board stop cocks had been removed from our houses in Drummond Street. This was true of no 119 – the stop cock in the pavement outside was missing and concrete filled the hole. Luckily, the charming and friendly Jeyant Patel of the Diwana restaurant next door allowed us to use his toilet in the front area of the restaurant. There were showers at Euston Station a few hundred yards away and there was a bath in the squatted house opposite which we were allowed to use although this required a booking system and crossing the street with towel, soap, shampoo, change of clothes and candle and matches as there was no light in the bathroom.

The following week we got our electricity switched on. In those days the London Electricity Board (LEB) was unconcerned about your legal status in the property . Any prospective customer in occupation of a property wanting electricity could open an account and get connected.

It was a bother not having water however. Some days after we moved in, the ever resourceful Barry Brookshaw was exploring the front pavement in front of Sacha’s house at 117 and looked into the water board manhole. It was not full of concrete after all and the stopcock was intact. Barry got a big spanner, turned the key and out came a jet of water. We were in business.

Barry quickly attached a pipe to the stopcock as the lead piping into 117 had been removed. He brought the pipe into 119. We connected it to the cistern in our outside WC and plumbed up our kitchen sink. Then the pipe continued into 117 along the back wall so that Sacha and Jamie could have water too.

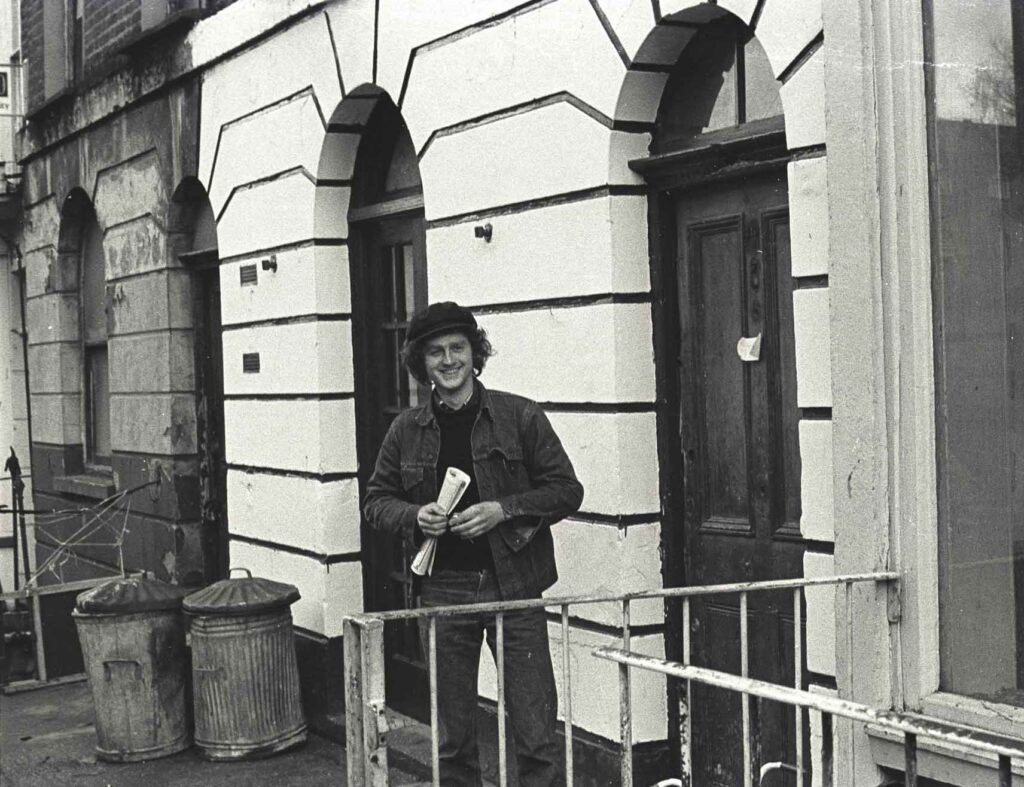

The house rapidly smartened up. We cleared our back yard of junk and made a doorway into the yard of 117. Barry painted the front render in cream and picked out the lines radiating away from the door and windows in brown.

We now had a fully functioning kitchen and I installed a darkroom in the windowless basement. I bought some brown velvet curtains from Simmonds second hand furniture shop on North Gower Street to keep out the draughts from my windows.

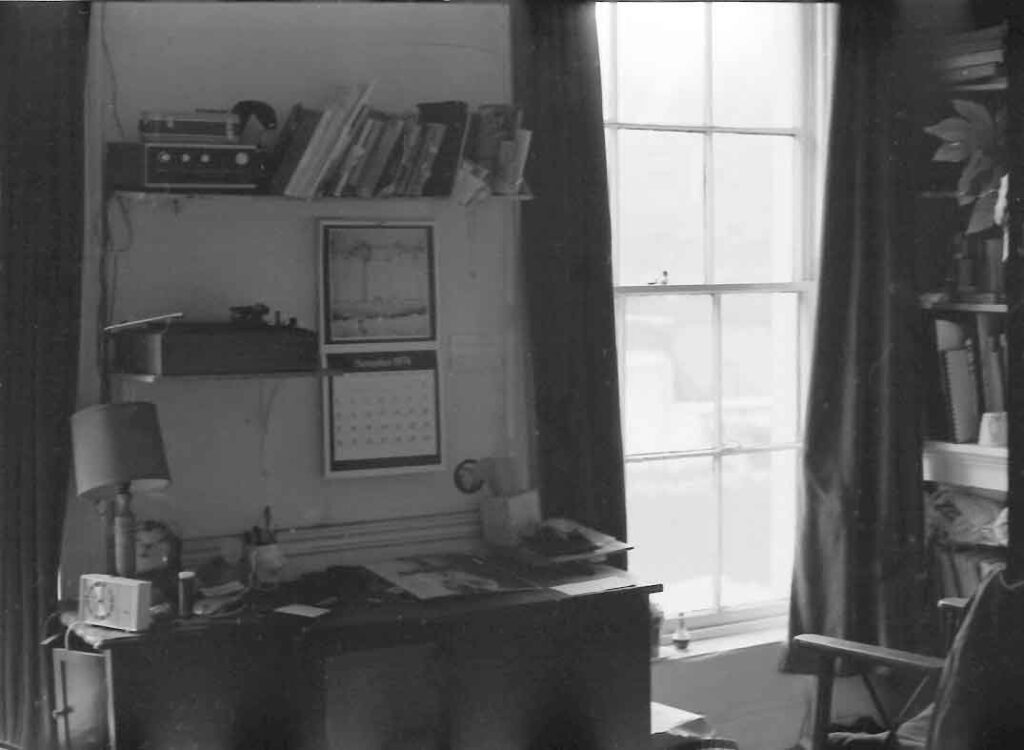

I quickly made my study bedroom comfortable.

Meanwhile I got to know my squatting neighbours. Most of them turned out to be about my age and had recently graduated from university. Not long after I arrived, Corinne Pearlman moved in next door to 117. She was a friend of Jamie’s from Oxford and they had agreed to share a house in London together. She took the top floor rear bedroom. Corinne had a proper job working at Age Concern, Tooting as a press officer. Then Orlando Gough, Jamie’s brother, and his partner Celia Keyworth moved in to the basement in 117. Richard Krupp, an American advertising executive and Jamie’s boyfriend, was a regular visitor. Jamie was a pianist and installed his upright piano in the front corridor. We played Bach and Handel flute and piano sonatas in the draughty and ill lit passageway.

Next door at number 115 Ethel and John Vine ran their shop selling groceries, provisions and sandwiches. This could not have been more convenient for our shopping for bread, butter, milk and eggs.

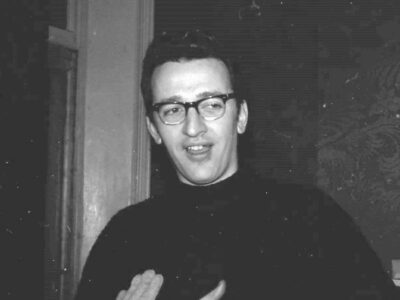

Opposite our house was the Tolmers Village Association, a community organisation funded by the Rowntree Foundation. The office was run by Nick Wates who had just graduated from the Bartlett School of Architecture and planning at UCL on the other side of the Euston Road.

Nick was squatting at 12 Tolmers Square with a number of fellow architects: Pedro George, Caroline Lwin, Barry Shaw, Atalia ten Brink and Douglas Smith. It turned out that some of them had done a project on Tolmers Square as part of their degree, examining the problems of development and planning blight. In the course of their site visits they realised that this would be a good place to live and were among the first to move into Tolmers Square in September 1973.

Drummond Street food coop

We decided that it would be a good idea to organise a food coop. This involved a 6 am trip to Covent Garden, then London’s main wholesale fruit and vegetable market, which was less than a mile away.

We drove there in my Hillman Super Minx. Getting close in the car was tricky with so many lorries and porters. We bought boxes of mushrooms, tomatoes, salad and vegetables, then sold them on the same morning at cost from our house in Drummond Street. I felt we should sell at just over cost to cover losses and build up reserves but was outvoted…

In February 1974 I finished at the Debden building site and began my course at the College of Law, Lancaster Gate. I cycled there and back for classes which ran every day from 2pm until 5pm. It was a gruelling crammer ending with 6 exams in a row in the cavernous hall of Alexandra Palace where pigeons flew around the rafters and sent droppings on to the candidates below.

In October 1974 I started work as a trainee solicitor (articled clerk as we were known in those days) at the trendy law firm Offenbach & Co in Bond Street. This job came in very handy for the legal battle which commenced in 1975 (see my story, The Legal Battle).

Our house at 119, one of three in a terrace owned by London Transport, was earmarked for demolition in the forthcoming redevelopment. We were given due warning and in the summer of 1975 I began preparations to move to my next squat, the first floor flat at 11 Tolmers Square (see my story Ringside seat).

Eventually the houses at 115-119 Drummond Street were demolished and replaced by three houses of a dull, modern design of similar proportions with shops below. 117 and 119 now contain a Bengali groceries and spice shop where I buy my rice and spices to this day. If only the original building had been restored however.

The Carnival 1974

The 1974 carnival was the first of several held in Tolmers Village organised by the Tolmers Village Association. Camden Council gave the Association a grant. We put up bunting along Drummond Street and North Gower Street. There was a jumble stall, vegetarian takeaway and stocks where you could throw a bucket of water over someone’s head poking through a hole.

My contribution was a chamber music group comprising two flutes, cello, violin and viola which played Mozart and Beethoven sonatas on the pavement next to Simmonds in North Gower Street.

In the square was a steel band and a rock band. I took two rolls of black and white film (Ilford FP4) that day which provided many memorable images

Looking back, it seems amazing that by the time of that first carnival in June 1974, I had only been living in Tolmers for 9 months but in that short time had created a home, become part of a thriving community and found more than a dozen new friends who became friends for life.

Read more about the author Patrick Allen

More stories

Squatting law expert

by David Watkinson

“My learned friend has a whole army of people to assist him, while I have only my solicitor and a clerk”.

Turning point

by Suzy Nelson

It was a turning point in my life. I was wanting to find an alternative way of living and engaging in community politics.

Wait until the head teacher sees this

by Oscar Gregan

I skimmed though the paper looking for the photo. I could not find it! I was just about to return the paper when I noticed the front page.

Squatting under the bridge

by Andrew Milburn

I chose London because … well, London. I had grown up in a coal-mining town “up north” and wanted to go to the big smoke, where the ground-breaking stuff was happening.

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.

Ahead of the game

by Orlando Gough

I am twenty-one and I’ve lived a privileged, you could say molly-coddled middle-class life. I have been to London before but I’ve never lived there. And here I am, right in the thick of it,...