It was the early seventies. May 1968 and the sexual revolution were still in the air, Marcuse and Reich. As students, ‘the revolution’ of not having to pay the rent was a first step in other forms of emancipation, freeing up the material and imaginative resources to fight the Tolmers campaign and to be experimental with our lives.

Most of us were neither full-blown libertarian socialists nor anarchists. Although some of us wanted to believe that we were revolutionaries, our revolution, for the most part, was a more intimate and local affair of squatting and living communally.

Squatting enabled us to narrow the gap between work and pleasure and between work and intellectual debate. Paying rent would have pushed us away from the city centre, away from our universities – alienated us. Everything was within walking distance. Each night coming back home, there was food and someone to talk to. Ideas and relationships were transformative. Life felt like an affirmative event.

These houses were empty, some of them for twenty years. Dilapidated, dangerous structures, still immune to the imperatives of for-profit development. Imperatives which have nothing to do with what people truly need the inner city to be, nor with a coherent vision of urban planning or design. We campaigned the English way, largely within the system. Politely.

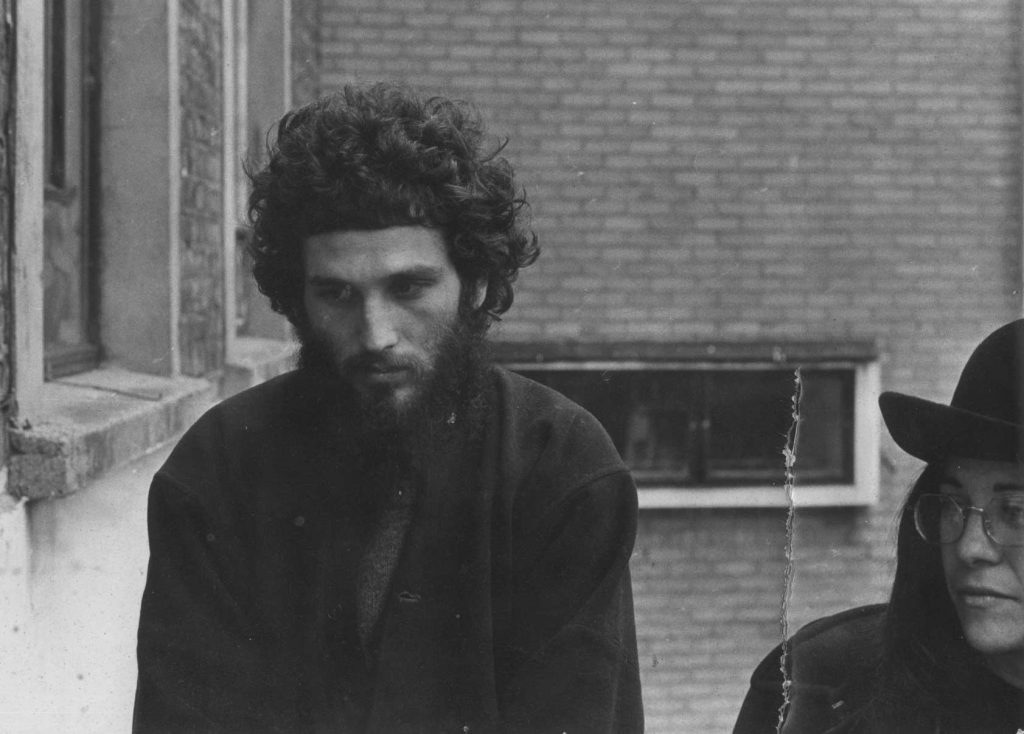

I’d been involved in left wing activism in Israel / Palestine before I arrived at the Square. Communal living was something I was familiar with, as I’d spent the summer months as a teenager taking part in the early Zionist communes, or Kibbutzim. But I was preoccupied with the aftermath of the ‘67 war. The ever-expanding occupation of the Palestinian territories. I was flirting with anti-Zionist ideas and with all stripes of Marxism.

In 1970, I’d enrolled on a degree course in 3D design at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem. After two years I decided to take a year off, looking to work in a studio in Finland. I was into the Bauhaus, Alvar Aalto, and so on. My boyfriend of several years had studied architecture, as the son of a Jewish architect who’d been expelled from the Bauhaus during the Second World War. My own family are Eastern European jews who’d managed to escape the Nazis in the ‘forties. It was against this background that I felt moved to spend some time in Europe, not because I had any plans to live or study there.

My new boyfriend in Jerusalem was an English student at the Bartlett. He’d come to do his Part II with Zeev Rechter, a pioneering architect in Palestine under the British Mandate, later Israel. He convinced me that I should come to London. That I could go on to Finland from there.

I arrived in London in July 1972. I lived, at first, with an American psychoanalyst in Hendon. He was a spitting image of Alan Ginsburg. Unable to process the discovery that his son was gay, he had closed his clinic in New York and was now busy experimenting with psychedelic therapy in London. The others were psychologists, hosting encounter groups and building domes influenced by Buckminster Fuller in our garden.

Later, I moved to Highbury New Park, together with a group of Bartlett students. Caroline Lwin was a frequent visitor. Through her, I met Barry Shaw, who was on the same course at the Bartlett as Nick, Pedro and Douglas.

Without having formally applied, I was offered a place on a degree course at the Central School of Art and Design in Southampton Row. I had to make up my mind: to take the place at Central or go back to finish my degree in Jerusalem. It wasn’t an easy decision.

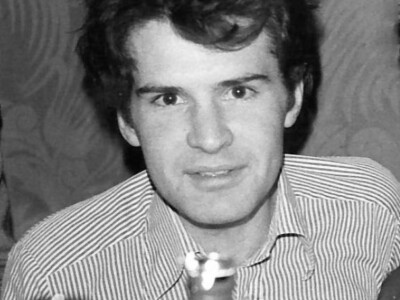

Barry and Caroline persuaded me to accept the place at Central, and I returned briefly to Haifa to get myself organised. Before I’d even finished packing my bags, Barry rang and told me he was moving into a squat in Tolmers Square. In Euston, walking distance from the Central. Would I like to join him? He’d already finished his degree and had learned about the square as part of his studies.

I liked the idea. As a foreign student, it was an opportunity for me to get involved in local politics. I would ‘get to know’ the British. I’d have more time to pursue my creative and intellectual interests.

In October 1973, one month after I’d arrived at Tolmers, during my first term at what was then The Central School of Art and Design, the Yom Kippur War broke out.

I decided to go back home. I had to sleep on the floor of Heathrow airport for three days before I could get onto a flight. The planes were taking men first; young foreign students who were all reserve soldiers in the Israel Defence Forces. I spent the war months working in the hospital in Haifa, my home town, where my mother worked. The hospital was downtown by the port and I still remember our evening walks together scaling Mount Carmel to get home after our shifts were over. I was away from London for several months and only returned for my second term.

My degree course was intense and I was in the studio all day. In the evenings, I worked as a colorist on animation films for a studio on Wardour Street, and as a silver service waitress at the Reform Club on Pall Mall. I was dreadful at it. Too busy looking up at the palatial ceiling or listening in on the retired Lords. Giving the clients the wrong cheeses.

Overwhelmed, I was only partially involved in the political life of Tolmers. I went to most of the housing meetings, the demonstrations; helped with some of the work involved in the campaign. But not as much as some of the others. Nick, Caroline and Patrick were the driving force.

As an Israeli, I was drawn to meetings organised by Matzpen: a revolutionary socialist, anti-Zionist organisation that had become notorious back home for its opposition to the 1967 occupation. They found an easier reception from among radicals in seventies London. I also occasionally went to the International Marxist Group’s meetings in the Square, captivated by Tariq Ali. But I was not a member of either organisation.

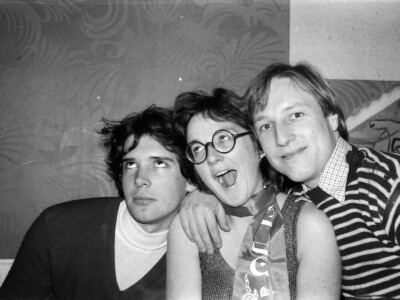

There were other groups, which were politicising the arts and culture. I became friends with members of the Poster Collective who were squatting in a big studio on the other side of the Square. They had formed as a group in the Slade School of Art and produced posters and films in response to the miners’ strikes, the wars in Vietnam and Ireland, and other anti-colonial, anti-racist and feminist struggles. They later founded Faction Films. I still see some of them today.

I remember one afternoon, seeing a tall, black cloud of smoke emerging from a window on the second floor opposite our squat at number six. I immediately called the fire brigade. The sirens sounded across Euston Road. They raised ladders, it was all very dramatic… only to find a woman happily making chapatis… The firemen kept telling me, “No, no, you did the right thing…”

I learnt all about Irish politics from the ‘Troops Out’ student campaigners who lived with us in Tolmers. The Square was full of predominantly English upper and middle class students, enamoured with radical politics. They were amazingly resourceful and quickly learned how to hammer doors, connect electricity, provide us with running water, knock down walls and transform rooms with wonderful wallpaper. I’d lived in modernist Mandate-era (1923 – 1948) buildings or in prefab mass housing blocks that had been built to accommodate fast arriving immigrants to a young nation state. Wallpaper was considered passé. Decoration was a crime.

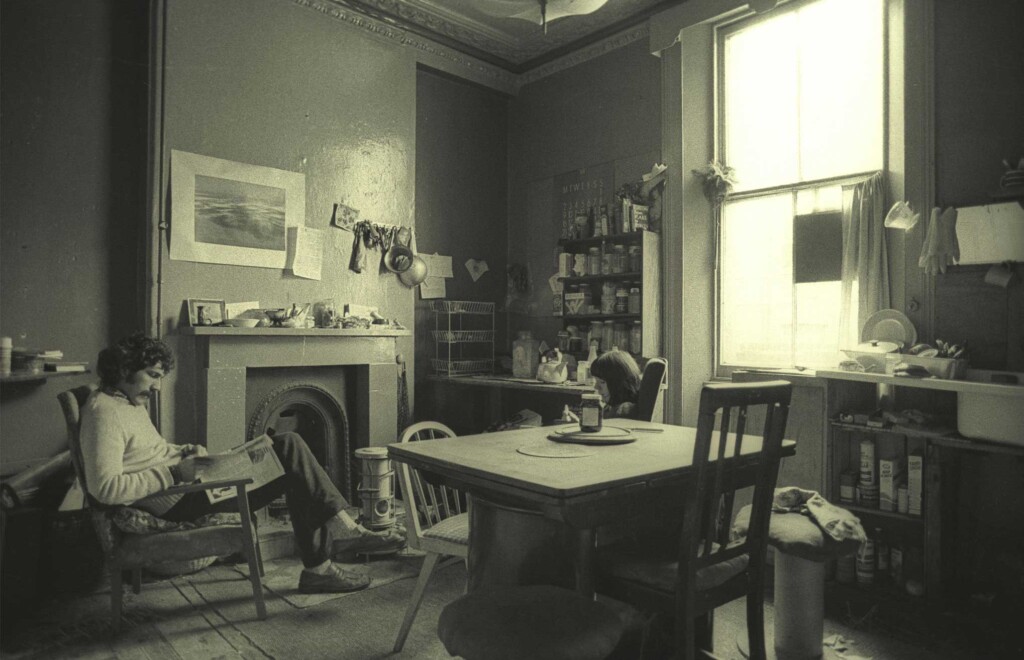

I remember how we stripped the lino floor at number twelve layer by layer and found, between each layer, incredible newspapers from the war years, and even earlier. We decided to stop at the 1920s.

In 1975, Barry and I squatted 6 Tolmers Square, taking the whole of the third floor. We were joined by Becca Cadbury, a friend of Sacha’s. This opened up a space in number twelve for Cora, Jamie and Sacha, who were now able to move in from Drummond Street, which was about to be demolished. It was only a few doors away, so we were still with them all really.

Barry and I were then joined at number six by several Israelis, mostly postgraduate students in the arts. They were immersed in their studies and barely got to know the British crowd. They also kept at a distance from local politics. Like the British, we were all middle class foreign students. Although we had to work, we were not hard up. We were privileged kids.

Number 6 suffered from a terrible subsidence. The front wall was separating from the building; we lived on the top floor and could see the sky. So we stuffed the gap with newspapers. Barry and I lived there until we were evicted in 1979. It was a comfortable house. Looking back, I don’t understand why we didn’t install a shower or hot water… hopeless! I came back from the studio at Central covered in dust. So I’d go to Euston station, where one paid 50p for the use of the commuter bath. I did this every day for six years…

My foreign student visa eventually lapsed and so, on 29 January 1977, Barry and I were married at Camden Town Hall. It was the only way for me to stay and work in the UK. Cora designed the wedding invitation, Patrick took wonderful photographs. It was a cold sunny day and after the ceremony we all walked back to Tolmers, joined by many others, and threw a big party at number six.

One of our dear guests was Auke, a leader in the squatting movement of New Market Amsterdam at the time. He remained a lifelong friend until he passed away a few years ago. I am still a close friend with Tjebee, an artist and activist in the Amsterdam squatting movement who lives today in the same house he then occupied. He’s never left it.

Bill and Oscar, Barry’s colleagues from the Camden Architects Department, came as well. Bill was my best man. Sadly, he died of AIDs in the 1980s. My senior tutor at the Central, Dan Arbeit, gave me away. Neither of our parents were there.

After our eviction, we didn’t want to be rehoused and moved instead to Newington Green, where we bought a four-storey house with a full mortgage from the Greater London Council . In the early eighties, I moved from design to film and video art. I later met and married Joram ten Brink, a professor of film and a filmmaker. We have a lovely daughter who, like him, makes films.

Some of the people who lived with us at number 6 Tolmers Square:

Professor Dan Bucsescu. Architect, Professor at Pratt University New York. Lived with us in 1975. He was doing his MA in Environmental Psychology in Guildford University at the time.

Omri Ethan. Architect and critic. Studied at the AA and now lives in Tel Aviv.

Eva Johansson. Vice President of Quality and Regulatory Affairs at two big hospitals in New York.

Dr. Gabi Klasmer. Artist. Studied at the RCA. Now lives in Tel Aviv.

Jani Klasmer. A photographer who still lives in London.

Esther Knobel, Artist and jeweller. Studied at the Royal College of Art. Lived with us for two years.

Dr. Gideon Ofrat. Art historian, art critic, curator. Lived with us in 1975. Lives in Jerusalem.

Mishael Rapp. A painter, studied at St. Martin’s, then in New York. Now lives in Klil in the Galilee.

Orly Yadin. Film producer and Executive Director of the Vermont International Film Foundation. Lived with us in 1975.

Read more about the author Atalia ten Brink

More stories

Those were the days

by Michael Fitzpatrick

We enjoyed the flourishing social scene centred in Tolmers Square, where a derelict bank was the scene of orgiastic gigs and periodic carnivalesque celebrations.

Rebirth through fire

by Alex Smith

I liked the dynamics of Tolmers Square. I was now on the South side where we were eccentric and unconventional, a bit wacky.

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

The best thing I ever did

by Douglas Smith

Number 12 was damp and stank of cats, the ground floor window was bricked up and there was water but no plumbing.

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.

The Christmas banquet 1975

by Patrick Allen

The turkeys cooked all afternoon in the four separate houses and were then carried across to Drummond Street with potatoes and gravy.