Looking at these 50-year-old photos, it’s crystal clear that all those elegant, characterful old houses should have been restored and preserved. Tolmers today is a very poor substitute.

I eventually got a council house but only because I had a child. Today’s tickets to affordable housing are old age, disability or children, with thousands of council bureaucrats weighing up competing needs – what a waste of human potential. Squatters repaired houses, sold food, organised community events and meeting our own needs was satisfying. Please could someone design a model for young people to access affordable housing in exchange for house restoration.

I don’t remember precisely how I came to Tolmers – probably by knocking at 12 Tolmers Square or 102 Drummond Street (The Dairy). I was 23, flat-sharing in north London and always broke after paying rent.

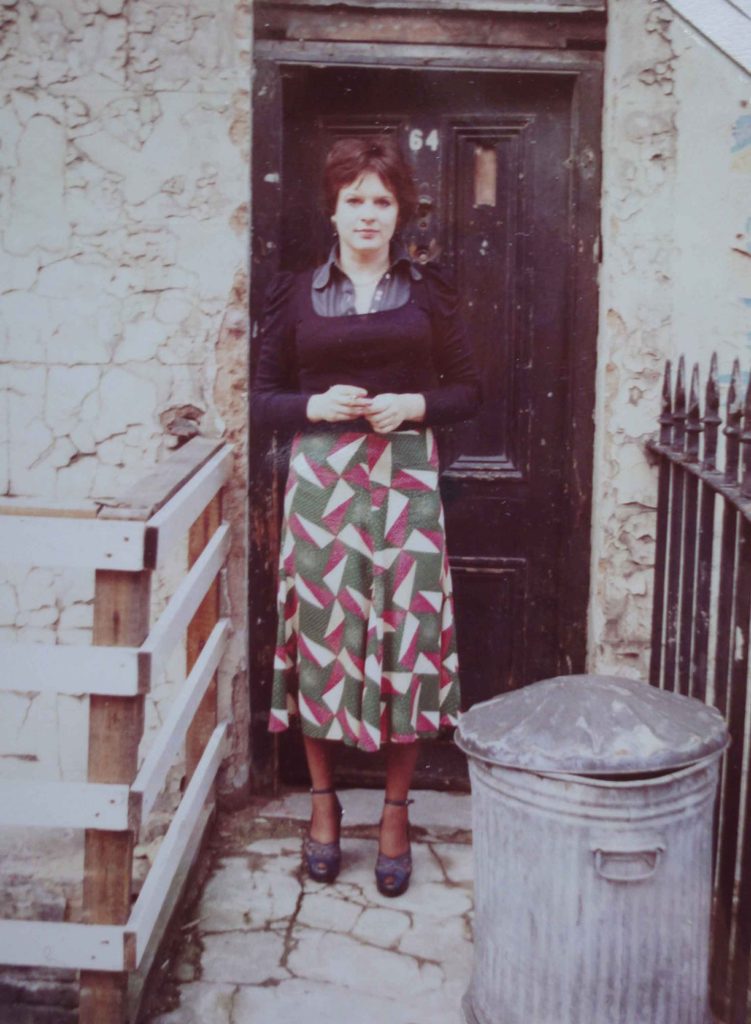

An empty commercial building at 142 Drummond Street was being squatted and I moved in with a couple of suitcases, the first – and only – resident. As soon as it rained, cascades of water streamed down. I moved my bed to the only dry spot on the first floor. Luckily, a few days later news came of a new squat – 58-66 Euston Street, starting with number 64.

The windows had been breeze-blocked up, but the window frames and glazing were inside and intact. The two windows in the living room on the first floor also had their original wooden shutters. Every room had a simple fireplace. Although small, the houses had lovely proportions.

Alex Smith writes that nine of us slept in the same bed (see Rebirth through fire). Was it really that many? It wasn’t as cramped as he implies – the bed was several mattresses laid together in the top front room. Numbers varied nightly as people made the adjoining houses habitable. I stayed at no. 64 with Ruth Ingham and Taddeo, a calm monk whose order had told him to live in the outside world for a year.

I painted the kitchen in gloss white and pale yellow, but it didn’t look right. Ruth, always blunt, said, ‘You’re trying to make it look clean but these colours don’t work in an old house.’ We mixed in some dark stains and in off-cream and muddy pink the kitchen looked much better. And counter-intuitively, just as bright. Ruth could have designed all today’s historic paint ranges.

Soon after, Ruth got together with Alex and moved next door; Suzy and Frances lived in one house; Ruth Milburn moved into 70 and the house in worst repair, 68, became a workshop. Then Debby, Al and Oli came over from 6 Tolmers Square.

Alex put in a ring main for electricity and I took responsibility for the bills. We never got running water, so had to fetch it in containers from a tap at the petrol station on the corner. One day the tap disappeared. After that we filled up at the Dairy.

Once, queuing for a bath at the Dairy, Peg Leg Pete (see Room at the top) was complaining about his hair, so I shampoo-ed it for him. Pete was happy but someone said, ‘You really are a cleanness freak’.

I had a day job as a secretary, then researcher, at the Sunday Times Magazine, which was walking distance away. On the seventh and last floor was the Editor’s Suite that the paper’s then-editor, Harold Evans, the anti-Thalidomide campaigner, never used. I discovered it had a substantial bathroom and started bringing my laundry in to wash in the bath after work.

One evening, the suite was no longer empty: a silver-haired gent, the lawyer who checked final copy, was working away at the large desk. He seemed tickled by the bathroom-laundry and never reported me.

Reading the stories on this website, I’m struck by how much I missed – I never heard Jamie Gough sing ‘All Shook Up’, nor realised how many musicians lived nearby. But I wonder if any Villagers glossed over their bad experiences … mine came from the insecurity. So many people passed through the Euston Street houses, including Scottish Mick who left with my cassette player. After that I hid my 35 mm camera, but one day that also walked.

The drains in the Euston Street houses were all linked and once developed a terrible blockage. I got home from work to see Frank, an older resident, in Wellington boots wading through the stinky waters wielding a heavy pole. As he lived on another street, it seemed like exceptional community spirit. It wasn’t pure altruism: soon after that Frank and Debby separated from their partners and set up home together.

In 1975, Frank helped me out of a bind. I was struggling with my first freelance assignment, an interview with Bob Marley. The editor had rejected my first draft for being too reverential. Frank, who wasn’t in awe of anyone, patiently worked through it, asking questions until he’d talked me into the right mental space.

The Tolmers Village Association (TVA) sometimes sent people round looking for temporary accommodation. A young Irish couple stayed for a month – they’d eloped and needed 3 weeks residence to marry. A mother in recovery stayed several weeks on route to getting rehoused. She had two children at primary school, both cheerful, cheeky and seemingly unscathed by the drug years. They’d just had a stroke of luck – she’d found a large stash of old notes up the chimney in her previous squat.

There was one packed TVA meeting when two Irish solicitors got up to explain that they’d come from Dublin to learn about Tolmers’ difficulties as they were about to launch their own battle and wanted to pre-empt the obstacles. In retrospect, Camden Council seems pretty spineless.

We heated 64 Euston Street with a coal fire in the living room. Delivery was every Thursday. Before going to work, I’d put the back door on the latch and leave money next to the hearth. The delivery man came in through one of the other houses (we’d knocked down the dividing walls between the back yards), carried the coal across the yard and then up the stairs to empty the sack straight into a huge Chinese earthenware pot, which we’d got from outside one of the Drummond Street shops – they were the containers that Chinese eggs were imported in.

If anyone ever writes ‘Tolmers, the musical’, it should include the coalman scene: a friend was having an affair with a journalist at work and I loaned her my keys so they could meet at no. 64 during the lunch hour. When they heard the heavy steps coming up the stairs, they were both naked and had just enough time to hide behind the sofa. They heard the coal clattering into the pot, then the steps retreating. They’d just emerged when the sitting room door burst open again. ‘Scuse me’, said the sooty coalman, clomping across to pick up the money he’d forgotten.

My mother was a nurse, and while expecting me cared for someone in the Croom-Johnson family. David Croom-Johnson and his wife were my godparents. At the Tolmers High Court trial (see The Legal Battle), we waited in line, then went up one by one up to a mahogany table where Croom-Johnson sat in his robes. I don’t think we knew beforehand who the judge would be. Or I didn’t know. Or I did, but kept quiet …memory fails. Anyway, he asked his questions, but neither of us acknowledged the relationship. For a long time, I felt guilty and cowardly for keeping quiet – would they have thrown the case out if I’d shouted, ‘Uncle David, godfather!’? It wasn’t until later that I learnt the case was thrown out anyway.

Squatting enabled me to save for my belated gap year – £2 a week in an Abbey National Build Up Share Account. Perhaps it was Tolmers magic, for no sooner had I decided on Brazil as my destination than two Brazilians moved into Tolmers, one a young artist; the other, Sonia, Pedro’s partner. I still remember the important phrase she taught me in her Portuguese lessons: ‘Me da uma avelã’ – ‘Give me a hazelnut’.

ENDS

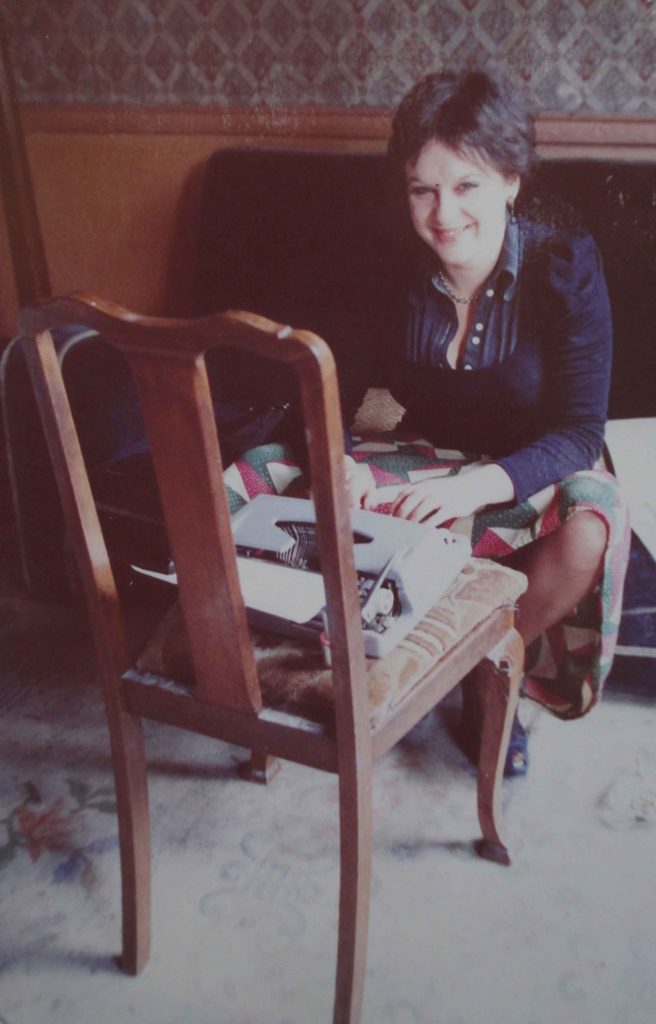

Read more about the author Moyra Ashford

More stories

No shame

by Tim Davies

A squat. I didn’t even know what that meant. I had to look it up – in the days before Google. Encyclopaedia Brittanica in those days.

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

Rebirth through fire

by Alex Smith

I liked the dynamics of Tolmers Square. I was now on the South side where we were eccentric and unconventional, a bit wacky.

Afterlife

by Alison Ravetz

It's wonderful to know that all that work and struggle are not relegated to a museum of good ideas, but are still being carried forward.

From Lisbon to Tolmers

by Pedro George

Tolmers made me realise that people are important in planning, you have to involve communities in decisions. If you fight a good fight, collectively, people can change their environment.

Squatting law expert

by David Watkinson

“My learned friend has a whole army of people to assist him, while I have only my solicitor and a clerk”.