as told to Patrick Allen

After leaving school I spent a year on a boat in the Pacific fishing with a rod for salmon and tuna. I managed to save about £10,000 in 6 months allowing me to be financially independent from the age of 18.

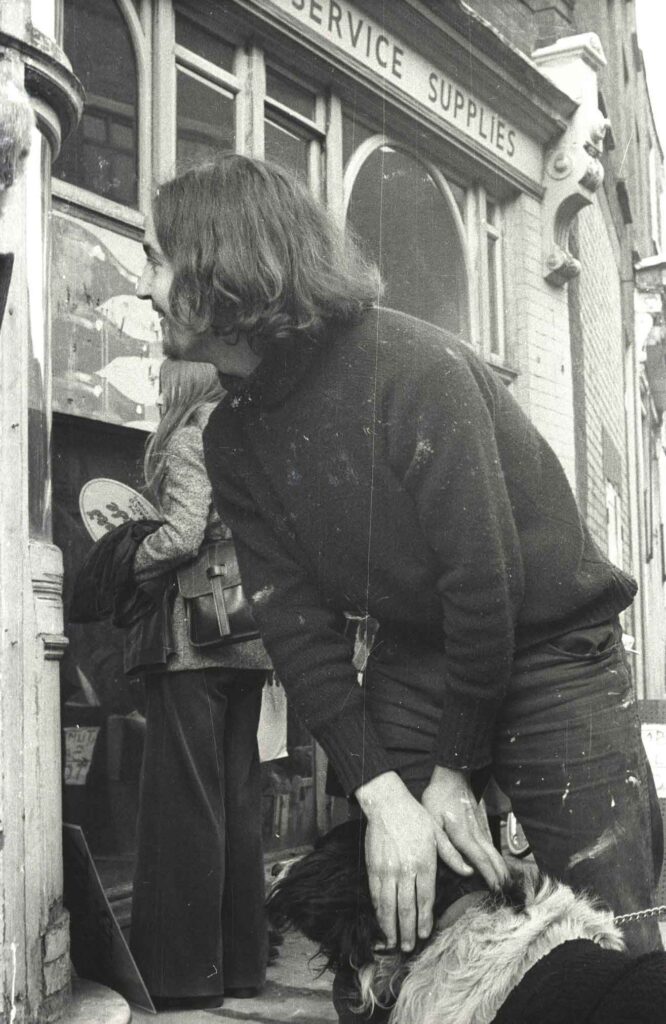

In September 1972 I came to London to begin my architecture studies at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London. I had nowhere to live so I stayed in a hotel in Bayswater. I talked to Nick Wates and Barry Shaw who were students on the same course. They were squatting in Tolmers Square. This sounded like a great idea and much better to have my own room than sharing a grotty room in a Bayswater Hotel so I decided to follow their example.

In January 1974 I opened up a house at 4 Tolmers Square. I could see that it was empty as it had corrugated iron on the basement window. I climbed into the basement and jemmied off the corrugated iron. Then I got in through the window and opened the front door. I got rid of all the rubbish and managed to fix the leaking roof where some tiles had been displaced. I worked out how to get the water and electricity connected. The water was turned off at the stopcock in the basement and all the internal piping had been removed. For electricity I had to apply to the electricity board and give them a deposit. Then I had to do some internal wiring to provide sockets and lights.

For a while I lived on my own in number 4. Then Debbie Banham, her partner Allan Arditi, and their 4 year old child Oli moved in. I had the top floor and they had the first floor front room with the balcony. We had a communal kitchen in the back room on the first floor. Oli called me Alex Dragon because I used to smoke a lot of weed and I could breathe it out of my mouth and circulate it up through my nose which fascinated him. I stayed at number 4 for about a year. I had been at the Bartlett school for about six months but then I dropped out. This was my first dropping out; there were several more. At the time it felt silly to be at the Bartlett learning how to build buildings when there were masses of buildings empty and waiting to be used.

I fell in love with Ruth Ingham and moved out of number 4 to a squat in Euston Street to be with her. That was quite an avant-garde place. There were eight or nine of us sleeping in just one bed including a Thaddeus, a Franciscan monk. This was a bit much for me, a young lad up from the country.

I started living with another Ruth, Ruth Milburn, in the house next door in Euston Street. This house was in a terrible state. Here, we never had mains water or electricity. I built a Savonius rotor on the roof to make electricity which I constructed from a 50-gallon oil barrel. The rotor made enough electricity to power a car headlight and charge a battery in the workshop. We trapped rainwater which provided our drinking water.

Most of our cooking was on a wood range, burning coal or wood and we had paraffin lamps for lighting.

The Camden planning department had offices next door to us. They saw the Savonius rotor on the roof, thought it wasn’t compliant with planning regulations (!) and came round to ask me about it. I explained what it was and they said ‘okay, its ‘plant’ and doesn’t need to comply with planning regulations’.

I was in Euston Street for about six months then ran short of money so went back to the Pacific for more fishing – two-man trolling with hook and line for salmon and Albacore tuna.

I returned to Europe and met up with Ruth Milburn in Finland where we stayed for a while. Then we came back and lived in Euston Street for about a year, once again without electricity or water.

Ruth and I separated and I moved to 19 Tolmers Square, a large semi-commercial building on the south side of the square which was ‘managed’ by another squatter, Vince Hetreed. I had spent all my fishing money and decided that the best way to morally oppose Stock Conversion and its property development was to live without money. In fact my father gave me a £5 note and I used it to light a fire.

I lived without money for about nine months and found this quite easy. For food I used to walk to the Covent Garden market with a pram and pick up fruit and vegetables which had been thrown away. When the market moved to Wandsworth, I went there by bicycle, a 30-minute ride, and again picked up thrown away fruit and veg.

Community Foods, suppliers of organic and natural dried foods, had leased warehouse premises on the corner of Tolmers Square. I used to sweep up for them and they allowed me to keep the sweepings which included rice and grains.

The other place for free food was the Eden Vale distribution centre near Regents Park. There was a skip where they threw away yoghurt and cream which had passed its sell by date. I helped myself to as much as I needed.

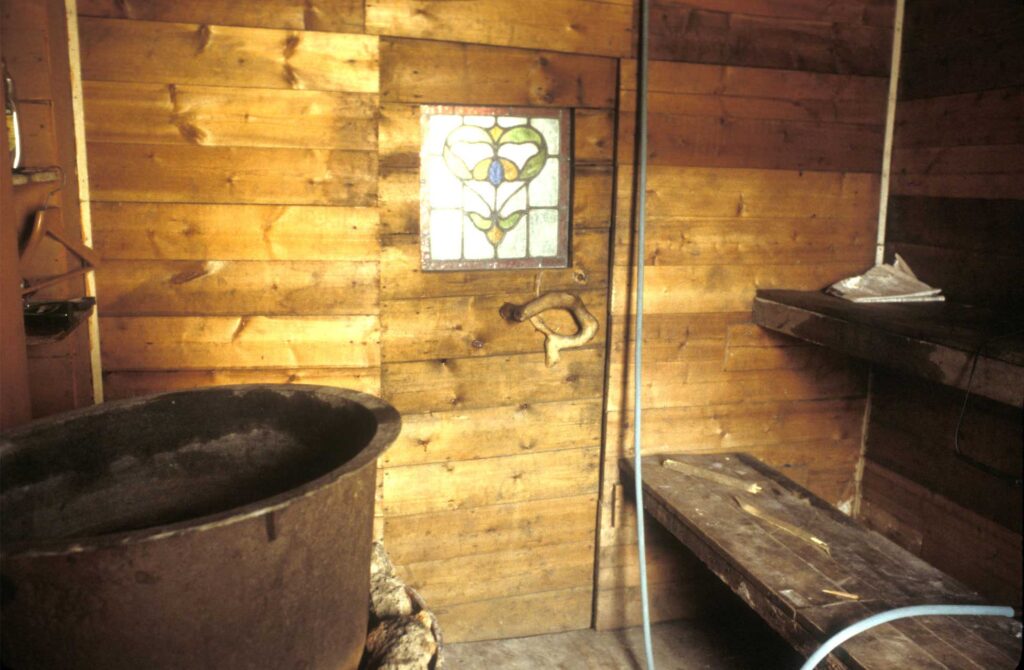

I gathered water from the roof of number 19 and filtered it with sand for washing and sand and charcoal for drinking. The water supplied a sauna bath in the basement which was heated using wood in an oil drum.

I directed the water into a 100-gallon storage tank for washing, then the overflow went into a small swimming pool which I created in the basement and from there it overflowed into the drains. The pool wasn’t very big – the size of two sofas and thigh deep, but good enough for a dip. It was more like a baptism. Heating and lighting was provided by wood found in skips. I made a bed inspired by the Arabian nights from an old parachute. I draped this around my bed on the floor.

I liked the dynamics of Tolmers Square. I was now on the South side where we were eccentric and unconventional, a bit wacky. I saw the North side squatters as the professionals – doctors, lawyers, architects, planners. However, we all came together as a community, especially for the carnivals.

It was at this time that I met Chiara and we married in Tolmers Square about 18 months later. The two of us lived together without money for a while but Chiara got fed up with this so we started to use money again. This was Chiara’s idea as I quite liked living without money.

We started our first shop after I found £2 in the street. This was our start-up capital. I borrowed a Morris Minor pick-up truck and drove to Covent Garden market. It cost exactly £2 to get the van into the Market. I worked hard and picked up discarded fruit and vegetables and put them in the back of the van. We squatted an old dairy shop at 191 North Gower Street on the corner of the passage to Tolmers Square where we sold the fruit and vegetables.

At the end of day one we had turned £2 into £4, doubling our capital! We carried on selling discarded vegetables for a couple of months then bought two bags of flour from Community Foods, bagged it up and sold it on. We weren’t competing with them as they were wholesalers and we were retailers.

There was an old gas oven in the dairy and I started making bread – about 15 loaves a day. We slowly turned the dairy into a wholefoods shop. We had no overheads and hardly any living costs.

We tried to open a bank account but the bank refused us (Nat West Tottenham Court Road, I think). After 6 months they relented and allowed us to open an account. We were evicted from the dairy as they were going to renovate it so we set up a shop in the ground floor of number 20 Tolmers Square.

The business was now taking shape. We had a proper shop with scales and stock. We started selling muesli in bulk, mixing it up in a 500 gallon storage tank, then bagging it in 25kg sacks. We sold this to customers of Community Wholesale as they did not sell muesli.

John and Vera Wood had been squatting at 213 North Gower Street where they sold wholefoods and muesli and recycled materials. When they were evicted we inherited their muesli recipe. One of the recipes that my current business uses is based on that recipe.

We ran the shop in 20 Tolmers Square until we were evicted in 1979. We then moved to a little corner shop in Cromer Street behind Camden Town Hall which was vacant. We bought the tail end of the lease for £500. We were there for two or three years before moving to a bigger shop in Marchmont Street. We bought a muesli mixing machine and put it in the basement of the shop. The shop was called Alara (from Alex and Chiara).

We transported the muesli in bulk in the back of an old ambulance. We drove to Community Foods who had moved from Tolmers to Brent Cross, collected other bulk items from them and delivered them around North London.

I kept an interest in the Marchmont shop for 20 years until my divorce from Chiara in 1997. At this point we split our assets. Chiara got the shop then promptly sold it. It is still going as a wholefoods shop called Alara so our name lives on.

I kept the muesli mixing and wholesale business which was now operating from premises in Camley Street. Eventually I stopped wholesale sales and concentrated entirely on muesli.

My muesli business, the first manufacturer to make no added sugar muesli, now employs 55 people and has an annual turnover of £7 million. My staff include a technical team looking after quality, accounts, logistics, buying, sales, and production. We have 6 mixing machines and 600 recipes. All the machines work on gravity, aided by compressed air. There are no tubes or channels and this makes it easy to switch from one recipe to another which only takes 10 minutes. We sell muesli, porridge and ‘super‘ foods. We buy the ingredients from all over the world – Peru, the Middle East, China and the Ukraine.

We grow grapes in our vineyard next to our office and factory. The grapes go to a wine maker and we get wine in return, this year 20 bottles of rosé. Next year we hope for 40 bottles.

We have 6 volunteers who help look after the garden. There are 200 fruit trees – grapes, mulberry, pineapple, guava, figs, pomegranates, Chinese pears, apples.

Community Foods is still in existence in Essex. It was bought by a dairy coop, then sold to the management team. We still do some business with them.

What did Tolmers mean to me? Did it change my life?

I wouldn’t be the person I am today but for Tolmers. Tolmers gave me the ability to go out on a limb – I could get up in the morning, put on my white rabbit suit and lounge around in the sun. I could live without money for a year.

It was an extreme form of freedom giving me the chance to experiment with life. It gave me the opportunity to understand things and to grow and to do things.

I learned how to start and run a wholefoods and grain business using the free premises we had access to in Tolmers. This was the foundation of my successful business today.

Quite a lot of the things I used to do in Tolmers, I have managed to recreate here in my factory. For instance we used to have big fires in the Square. We now have big fires and parties in the yard at Camley Street.

If I was to make any analogy, Tolmers was was like a fire which burnt off my childhood more than anything else could have done. I feel almost like a phoenix arising from that fire, a rebirth through fire.

My previous life was conventional with conventional aims. I was expected to qualify as a respectable architect, have a professional career, have 1.8 children and a good mortgage, be happy and comfortable ever after.

I have done this but in a different way. It hasn’t been all stress free but it has all worked out well. I feel very blessed with my life.

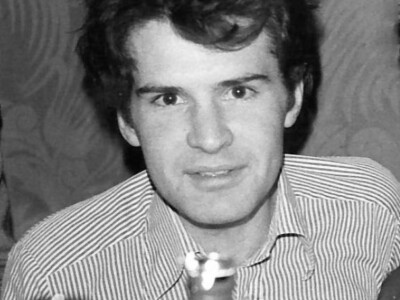

Read more about the author Alex Smith

More stories

Israeli outpost

by Atalia ten Brink

Barry rang and told me he was moving into a squat in Tolmers Square. In Euston, walking distance from the Central. Would I like to join him?

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

Those were the days

by Michael Fitzpatrick

We enjoyed the flourishing social scene centred in Tolmers Square, where a derelict bank was the scene of orgiastic gigs and periodic carnivalesque celebrations.

Singsongs, meals and Marxism

by Jamie Gough

He said “those two houses are still empty, nobody has squatted them, why don’t you come and live there?” I can still remember that moment.

Nine in a bed?

by Moyra Ashford

Alex Smith writes that nine of us slept in the same bed. Was it really that many? It wasn’t as cramped as he implies – the bed was several mattresses laid together in the top front room. Numbers varied nightly as people made the adjoining houses habitable.

The Christmas banquet 1975

by Patrick Allen

The turkeys cooked all afternoon in the four separate houses and were then carried across to Drummond Street with potatoes and gravy.