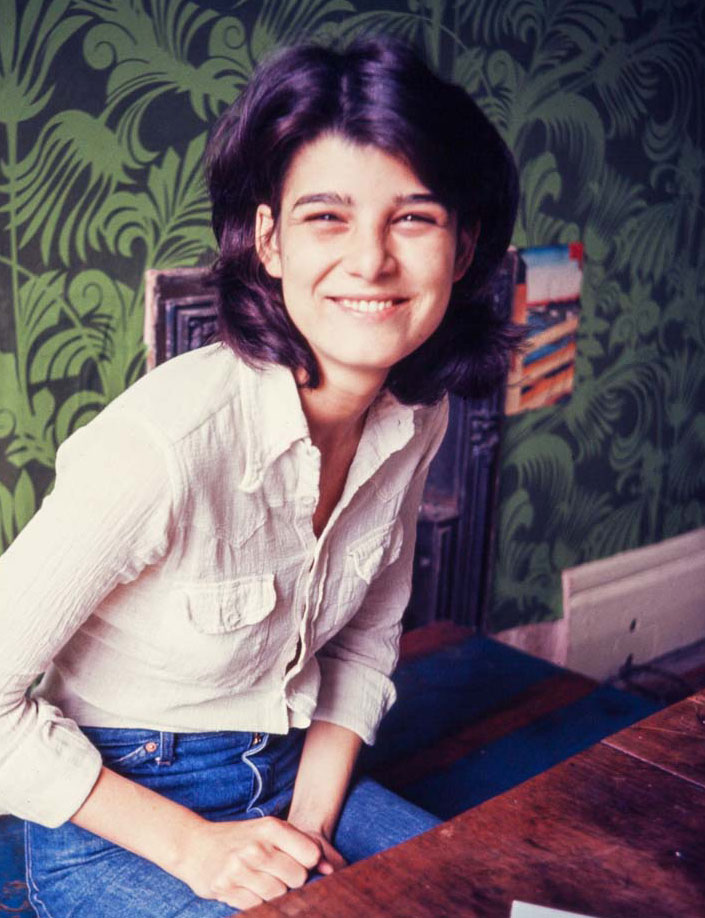

In September 1973 I was intending to move to London from Oxford where I had lived for the previous six years. I was hugely excited to start living in the metropolis – an ambition since I was a child. I was looking for a house to share with my friends – Corinne Pearlman, Sacha Craddock and Rod Smith. We were all moving to London for different reasons. It was hard to find an affordable house for four people to rent in London. I would go down to the Evening Standard offices at 6am to get the paper fresh off the press to find the adverts for rented housing, then I would run to the phone box and ring the number of possible houses. Invariably they had gone. Meanwhile, I was living with my boyfriend Richard Krupp, in Maida Vale.

The reason for coming to London was to do a master’s degree in Town Planning at University College London (UCL). At UCL I met an architecture student, Nick Wates, who came to a session of my course to talk about Tolmers Square where he and some others were squatting. This was a short distance from University College, just over the Euston Road. He gave an account of what was going on there, the property speculation that was happening, how lots of houses were empty and that many people had already started squatting them. I was intrigued. At that moment I hadn’t even heard of squatting or thought of it as something I might do.

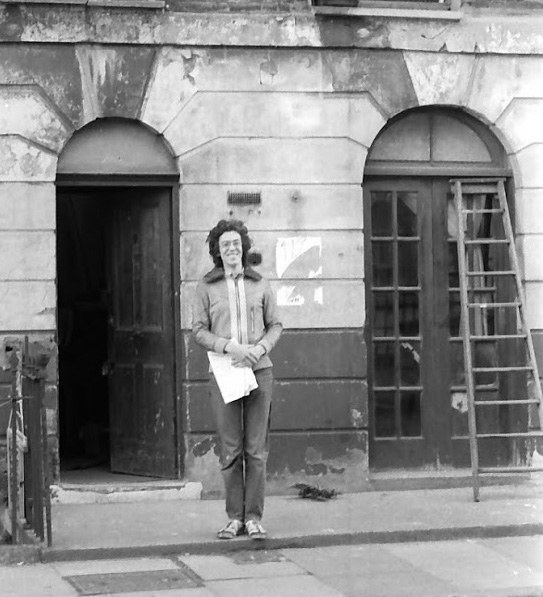

Shortly afterwards I went to Tolmers Square with Nick. He gave me a tour. We walked down Drummond Street and he pointed to 117 and 119, two adjacent houses next to the Diwana Restaurant. He said “those two houses are still empty, nobody has squatted them, why don’t you come and live there?” I can still remember that moment. I was absolutely amazed. I just thought “this is a Georgian house in the West End of London, and I can live there?”. It had corrugated iron on the front, but the front door was swinging on its hinges and you could walk in, because homeless people had sometimes used it. So, I got on the phone to Corinne, Sacha and Rod. They came round and had a look and we decided to give it a go.

On the moving in day, Sacha’s father John Craddock, drove to London from Oxford. He had a crowbar and he quickly demolished the hoarding in front. So in we went. We subsequently learned that the house had been empty for at least 20 years. We started to clean it out. John Craddock gave us some coal so we made fires in the lovely grate. Actually the coal was coking coal so it didn’t really burn but just smouldered.

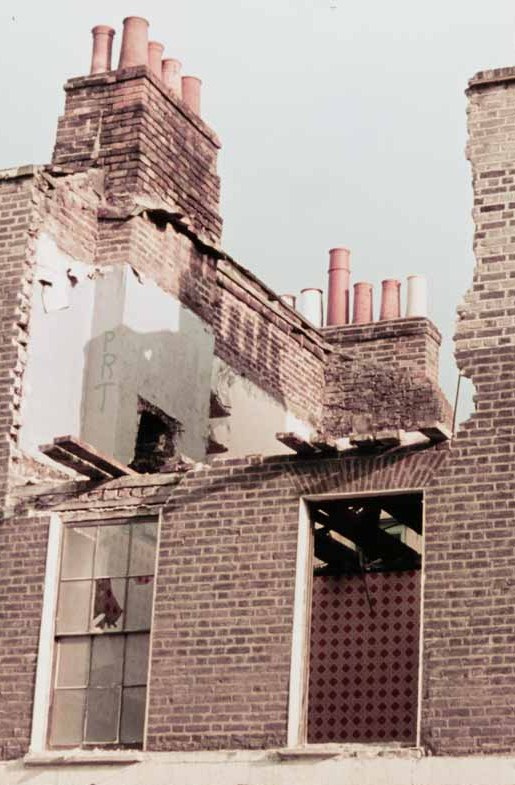

On the first night we slept in the downstairs room which we had cleaned up – me, Sacha and Sacha’s mother Sally. The next day we climbed out of a window into the back yard which was 2 metres deep in junk. From there we could view the back of the house. The gutter had been leaking and the water running down the back wall. It was bulging out and looked about to collapse. So we did a shuffle into the next door house, 117, whose back wall looked better. This meant abandoning all the cleaning up that we had done in 119 (much to the advantage of Patrick Allen who moved into 119 not long after! He wasn’t bothered about the wall.)

So, the four of us started moving into our house and doing it up. No water, no electricity, no gas. The plumbing had been pinched, but there was a gas cooker on the first floor. But in those days, the utilities were willing to connect squatters. I knew about electricity so I wired up the house; it took me three days work because I absurdly did it to building regs standard. We believed there was no water for these houses, but the resourceful Barry Brookshaw, who was now living in 119 pulled up the plate in front of 117 and found a perfectly respectable Water Board stopcock. He used a large spanner to turn it on – a moment of rejoicing. He connected some plastic pipe into 119, and connected their toilet and kitchen sink to the water, then kindly brought plastic pipe across the back wall into our kitchen in the first floor back room.

The Tolmers Village Association had set itself up in a house immediately opposite across Drummond Street which happily had a bathroom with a bath in it, to which hot water was connected. So we were able to cross the road and have a bath. We subsequently cleaned out the back yard and found the toilet there in working order.

Jeyant Patel, the owner of the famous Diwana Bhel Poori House next door, was a tremendous support in our early time in Drummond Street. The moment we appeared Jeyant came out and said “Ah this is wonderful, I support what you’re doing, it’s great that you’re squatting these houses. I am a Ghandian, I believe that property is there to be used, not there to make money”. He added “well, you don’t have anywhere to eat, so you must just come in and eat whenever you want”, which we did. Sometimes three meals a day, breakfast, lunch and dinner in the Diwana, fabulous food which he gave to us. He also allowed us to use the customer toilet in his front area. The only problem was that the toilet was plagued with the biggest slugs the world has ever known. I don’t know how we would have survived without Jeyant. Very sadly, he died young of a heart attack a few years later.

We put up some smart wallpaper in our living room from Habitat, a trellis-like design. It was the most beautiful Georgian room. All the woodwork had been painted dark green, which we kept. The two windows had shutters that went back into the wall between the two windows. The rest of the decoration in the house was a bit more approximate – a lot of white emulsion as I remember it. I had a piano in that draughty hall. I think we got it with other furniture from Simmonds, the second-hand furniture place which very conveniently was located round the corner in North Gower Street (now Patrick’s law office).

We had a problem with the roof. All the houses had shallow slate roofs which go into a gutter running from front to back, and the gutter leaked. Cora and I had our bedrooms at the top of the house underneath this roof, and we had buckets ready when it rained. We kept going up onto the roof putting more bitumen onto the gutter, but to zero effect.

The first three months after we moved in I largely spent doing up the house – a very bad start to my studies. Although it felt good to be restoring a beautiful house, it was also a chore. Once we had converted the basement by putting pallets on the mud floor, other people came to live with us, including my brother Orlando and his partner Celia.

A great thing about living in Drummond Street was getting to know people from the Bangladeshi community. I became close friends with a young man; he liked to hug and kiss me, and said that I was his boyfriend, though he didn’t present himself as gay in the sense that I was. To put it in academic terms, we had different socially-constructed sexual identities. In normal language, it was just lovely.

Eighteen months after we moved in, I was in bed late in the morning and I woke to find two guys in suits and ties with clip boards standing in my bedroom on the top floor. I said “Who are you?” and they said “Who are you? We are from London Transport, we own this house, you can’t live here”. That was very interesting because we had no idea who owned it. We had been there all this that time and had heard nothing from any landlord. I said, “we’re squatting here, and we’re going to stay.” I didn’t give them our names, to make it harder for them to get an eviction order. They slunk off.

It transpired that London Transport bought those houses when they were building the Victoria Line in the 1960s. We always heard the Victoria Line rumbling under the house. They bought these houses in Drummond Street as a job lot, and because they didn’t need them, they just left them empty to fall down and didn’t do any repairs.

After six months or so they did get round to evicting us, at which point Sacha and Cora and I moved to 12 Tolmers Square where Nick and a big household were already living. We were in there for four years before the final evictions in 1979.

I moved the piano from Drummond Street to Tolmers Square and installed it on the first floor in our huge living room, where we had many sing-songs. We would have dinner together, all ten of us or however many were in the house, plus visitors; we had an informal rota for cooking. Then as often as not I would get out the Cole Porter and My Fair Lady songs. That was a lovely aspect of life which I really miss now.

In number 12, there was a green dragon wallpaper from Colefax and Fowler, really dramatic, which made the room look sensational. In 1979 I moved from the basement of number 12 to the first-floor front room next door at 11 when Patrick moved out. I did a home-made version of the dragon wallpaper, using green paint and a mop, Jackson Pollock style, great green splashes going across the walls. Communication with number 12 was via the crumbling balcony – scary when I think of it now!

The last year I lived in Oxford, a Gay Liberation Front group started. I became involved in it, and I came out as gay through the wonderful solidarity of that group. When I came to London I asked around, and the most active Gay Liberation Front group in London was in Brixton, so I joined it. For the next 20 years, my main political thing was the gay movement.

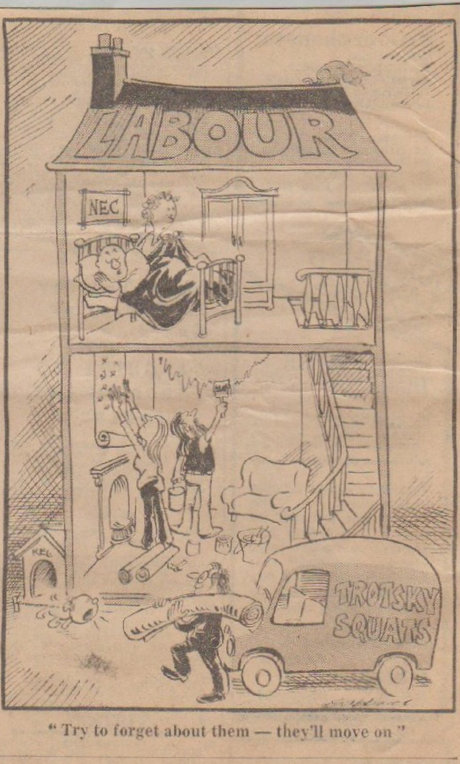

The 1970s were a period of enormous political conflicts: not only trade union struggles such as the 1973 miners’ strike but also the women’s and gay movements, and struggles over housing and public services. Initially through my studies at UCL, I was introduced to Marxism. Its first appeal to me was that it had a deeper analysis of homophobia and sexual identities than the ideas then current in the gay movement.

There were a lot of Marxist activists and intellectuals squatting in the Tolmers triangle, including across the square at number 14.

Sacha and I started going to local Marxist meetings. We were a bit overwhelmed at first, as there were people who had read the whole of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky. There were amazing discussions about capitalist history and the current situation in Britain. It was a great education. I became a Marxist writer, and over the next 50 years worked as a researcher and social science lecturer.

When we were evicted, Sacha, Cora, Dave Taylor and I wanted to continue living together. Sacha was insistent that we should stay in the West End and not move to the ‘suburbs’, meaning Hackney or Bethnal Green. This seemed utopian, until Dave saw an ad in the Evening Standard for a house to let in Central London. So we ended up in a five storey Georgian house next to the British Museum. Sacha and Cora are still there.

What was the best thing for me about Tolmers? Living in a neighbourhood with so many forms of cooperation, social and political; I’ve never experienced that kind of community living since. And living in a large household, with its everyday easy sociability. For the last thirty years I have lived either alone or in a couple, and I have great nostalgia for those collective households.

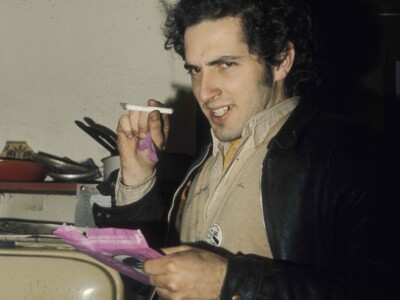

Jamie Gough

March 2021

Read more about the author Jamie Gough

More stories

From Lisbon to Tolmers

by Pedro George

Tolmers made me realise that people are important in planning, you have to involve communities in decisions. If you fight a good fight, collectively, people can change their environment.

Nine in a bed?

by Moyra Ashford

Alex Smith writes that nine of us slept in the same bed. Was it really that many? It wasn’t as cramped as he implies – the bed was several mattresses laid together in the top front room. Numbers varied nightly as people made the adjoining houses habitable.

Wait until the head teacher sees this

by Oscar Gregan

I skimmed though the paper looking for the photo. I could not find it! I was just about to return the paper when I noticed the front page.

Israeli outpost

by Atalia ten Brink

Barry rang and told me he was moving into a squat in Tolmers Square. In Euston, walking distance from the Central. Would I like to join him?

American architecture student

by George B Bryant

My living conditions were primitive but there was electricity, water and mail delivery. I don’t know what I would have done had I not been able to live there.

Double first

by Dave Taylor

Tolmers was life changing in fundamental ways, it took me into a whole different cultural milieu which was exciting, challenging and fun.