I’ve lived in a village in Suffolk for over twenty-five years now, but it’s never less than obvious that I’m not from there. If people ask me where I’m from I usually say Cambridge, as that is where I spent my teenage years, it’s the place I left when I embarked on my still unconsummated courtship with adulthood, and it’s where my mother still lives. But the place that I feel I’m from, the pool in which my roots are watered, is a tiny patch of north-central London, a roughly triangular slice of streets bounded by Hampstead Road, Euston Road, Euston Station, and the tracks that run out of it to the north. This area, in which I lived for barely three years, at an age too young to have any clue what was going on around me, or what any of it meant, was then known as Tolmers Village—and it’s the place in which I formed my most deeply held, and most radically mistaken assumptions about what ‘normal’ looks like.

Tolmers Village was a great place to be a kid—sometimes a dangerous place, for members of the small gang I ran with, and for the adults we occasionally terrorised, but a place in which we had the freedom to learn by doing, surrounded by grownups who were unlikely to harbour any old-fashioned prejudices about what children should or shouldn’t be doing or knowing. For example, I asked, aged three, what ‘sex’ was, having heard my elders discussing it, and was given a pretty detailed explanation of the mechanics. Among my earliest memories of our time there, during the brief period I lived with both of my parents, I recall being in our upstairs sitting room at number 4 Tolmers Square, and receiving an explanation of some of the knick-knacks my dad had kicking about the place. The cylinder with strings on was a tabla, an Indian drum, I learned; while the clay tube was a chillum, a ‘special pipe for smoking dope in’. At some point (I have no recollection of the planning stages of this operation), members of my crew of feral hooligans must have started wondering what happened if you set fire to a car, because on one memorable day we did graduate from liberating hubcaps to doing exactly that, in Melton Street along the side of Euston Station, if I recall correctly (which is admittedly unlikely). I was among the youngest in this crew, arriving in Tolmers aged 3 and departing at 6, but the eldest was no more than three or four years my senior. While I’m quite certain that none of our parents would have taken a tolerant view of that particular escapade, their approach to child-rearing at the time could be boiled down to ‘light blue touch paper and retire’. We scampered about on the roofs of the four-storey terraces, we poked about in building sites (on one of which I slashed my arm open on a piece of broken glass, requiring several stitches), we befriended local characters of unknown proclivities, and we somehow avoided life-changing injury or abduction. Although I was barely aware of them at the time, there was in fact a large circle of adults looking out for us, not just among the hippies and activists that had colonised the area, but also among the South Asian communities, into whose business premises we would saunter as though they should be delighted by a visitation from a gaggle of untamed, filthy, and arguably sociopathic street urchins. For the most part, however delighted they weren’t, they made us feel welcome. And through all of this, I learned some truly dangerous ideas, the ones that to this day form the basis of my understanding of the world. Most importantly, I learned that I’m entitled to my liberty, and that nobody is entitled to deprive me of it.

You can read plenty elsewhere about the community of squatters and activists in Tolmers Village, how they came to be there, and their history; but I think it’s important to the experience I had as a child that most people were there out of a commitment to alternative lifestyles, or to political change, or social justice, or urban regeneration. I learned that I belonged to a tribe of people who believed in living together with tolerance, in a community founded on justice, solidarity and equality; and I learned very clearly that there were a lot of people out there in society who would like to stop us living as we wished. I learned, in short, that what is generally held to be true and right is usually not, and that I shouldn’t go along with anything simply because most people seem to think it’s a good idea. Right down there, at the level of understanding so deep that it feels like instinct, I learned that authority is always to be questioned, always to be opposed.

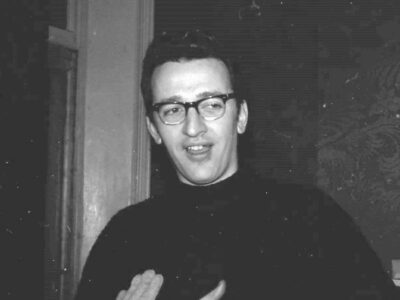

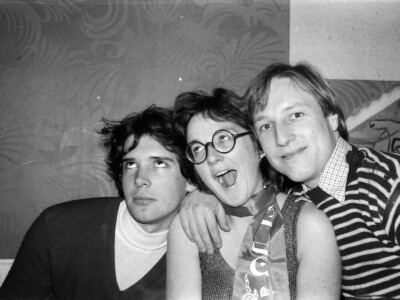

So Tolmers was not simply a rolling city festival populated by hedonistic heads: it was a community founded on activism, but there were doubtless plenty there who were primarily around for the sex and drugs — my dad Allan Arditi among their number, I suspect. He died on New Year’s Day 1980 in Goa, at which point I hadn’t seen him for the best part of a year—he was 28 and I was 9. My clearest memories of him are in Tolmers Village. After my parents separated he lived at number 14 Tolmers Square, at the opposite corner from number 4 where I lived with my mum, and I would visit him in his first floor flat, which he shared with an enormous Alsatian called Chief, and a collection of bandes dessinées which kicked off my lifelong enthusiasm for comics. So if Tolmers feels for me like the place where it all started, it’s probably related to this: It’s the place in which I can think of my parents as my parents. It’s the place in which I learned to recognise my tribe. I’ve kept in regular contact with very few people from those days, but looking at the photos on this website, the recognition is instant. All those young faces, much younger in the photos than I am now, are encoded indelibly in my neural networks. They’re my family, even if we’ve had little or nothing to do with one another for the past forty-five years, even if, in many cases, I don’t even recall their names.

One evening in North Gower Street I was standing roughly in front of the darkened premises of the Villa Bella café, in which most of us ate from time to time, when a police car drew up. I had just rung the bell for the top floor flat, in the house just to the left of Villa Bella I think—I could check the details with someone, but then it wouldn’t be my story. My story is the oneiric progress of the toddler picaroon that I was. I’m not even sure whose flat it was, but I know that I knew my mum Debby was in it, and I was waiting for someone to drop the keys out of the window so I could let myself in and go up to join her. Finding an unattended pre-schooler wandering the street at nine o’clock at night (or whatever time it may have been), the peelers unsurprisingly took it upon themselves to reunite me with my parents. After asking me a series of questions which I presumably answered with some reticence, having picked up on the way Tolmers denizens generally related to the police, they offered me a seat in the back of the car and drove me around the surrounding streets hoping I’d be able to point out my house. I imagine I just thought it would be pretty cool to have a ride in a police car. We eventually ended up back where we started. I don’t remember the details, or the words that were spoken, but someone threw down the key and I went up to join my adults.

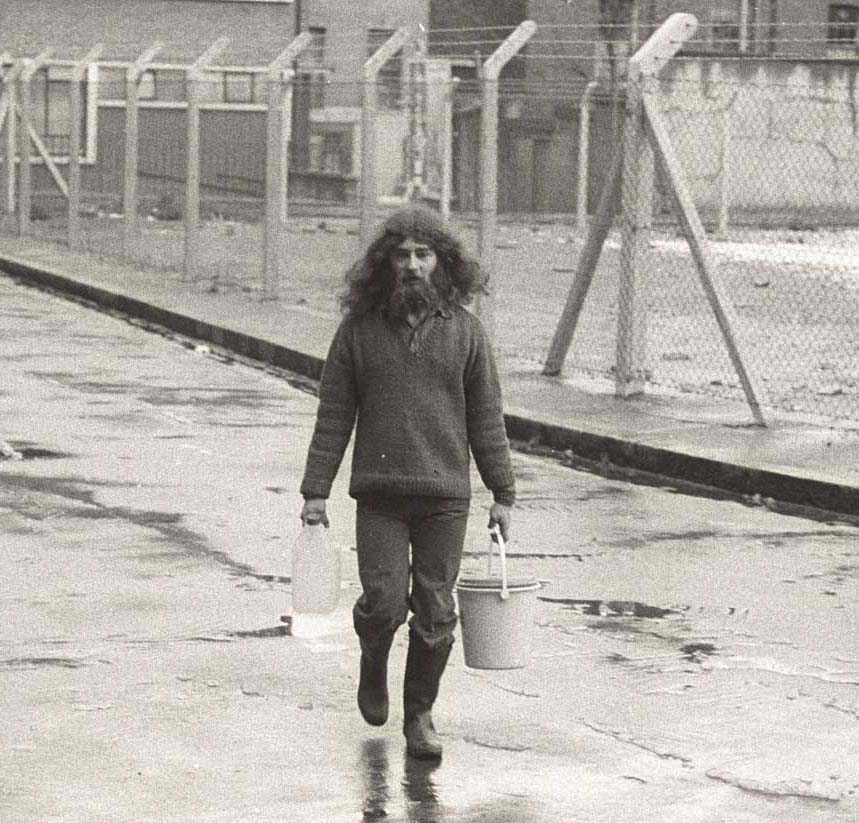

I’ve tried to describe Tolmers to my daughter Lucy, 22 years old at the time of writing. I never really managed. This website has opened a space for us to explore that, and for her to learn something about her own origins, one of the generational sources of the radicalism that she owns, articulates and lives so much more coherently than I do. When we looked through the beta version together, we were astonished by the quality and variety of the photographs, and more than that, by the way that they so clearly evoke a place and time—as much for her, someone who was born two decades after it all came to an end, as for me. I have very few photos of my father, and they’re all as familiar to me as my thumbnail, such well-worn images that they’ve almost lost the capacity to signify; so when I came across a shot of him lugging a bucket of water across the square (one of several pictures of him to be found on the site), it was an almost physical shock. I had my laptop on my knee, across the room from Lucy, and the tears ran freely down my face for some time before I was able to speak and explain why. For her as well, this encounter with her grandfather was a significant and moving event, which is not bad going for a website full of old photos.

My Tolmers story is not really a story, in the way that it is for someone who can say ‘I moved there at this time for this reason, and stayed there until x happened’. It’s a dream I had. It’s one of those vivid, surreal dreams, that keeps coming back to you through the course of the day. It’s a collection of images and impressions whose inner logic is strong enough to lend it a kind of coherence, but which evaporates if you try too hard to pin it down. It spoiled me for a normal life, in a way. I’m happy now in middle age, but for much of my life, through school, my reluctant flirtations with employment, and my encounters with bureaucracy in particular, there’s been a voice inside me, screaming that all this is wrong, that I come from a place where we do things differently, where we treat each other like human beings, that I can’t subjugate myself to these bizarre expectations that society has of its members. ‘I’m not a number, damn it, I come from Tolmers Village!’ Only more recently have I recovered the equanimity to just enjoy the opportunity of a ride in the back of a police car, as it were. With little or no baseline for normal behaviour in late twentieth-century Britain, I struggled. I dropped out, without any real idea what I was dropping out of, or what there might be to do instead. In my late teens I found myself squatting again, but not in the Tolmers manner: this was homelessness by any other name, occupying temporarily vacant rental properties for a few weeks at most, living in a myopic frenzy of psychedelic substance abuse. This phase only continued for a year or so, and I enjoyed it in a kind of timeless fugue state, proudly imagining that I was continuing an inherited tradition; but the hangover lasted a lot longer than the party. Afterwards I drifted, and eventually I wandered into a life, one in which I have been well-served by the independence and criticality that I learned at my mother’s knee, and on the streets of Tolmers Village.

Read more about the author Oli Arditi

More stories

Bourgeois squatting

by Corinne Pearlman

It seemed like the right way to live. It felt very comfortable for me, living with a lot of people. I’ve got various lives in different places, but that communal life is really important.

American architecture student

by George B Bryant

My living conditions were primitive but there was electricity, water and mail delivery. I don’t know what I would have done had I not been able to live there.

Wait until the head teacher sees this

by Oscar Gregan

I skimmed though the paper looking for the photo. I could not find it! I was just about to return the paper when I noticed the front page.

Squatting law expert

by David Watkinson

“My learned friend has a whole army of people to assist him, while I have only my solicitor and a clerk”.

Singsongs, meals and Marxism

by Jamie Gough

He said “those two houses are still empty, nobody has squatted them, why don’t you come and live there?” I can still remember that moment.

The best thing I ever did

by Douglas Smith

Number 12 was damp and stank of cats, the ground floor window was bricked up and there was water but no plumbing.