First published in ‘Goodbye to London: radical art & politics in the 70s‘, edited by Astrid Proll, published by Hatje Cantze, 2010.

We broke into our house with a “jemmy” crowbar, but it was easy, as it had been used as a sort of doss house anyway. We never locked the door once we took possession, but left the door open in honour of the people that used to crash down there. My bedroom was on the ground floor. We had no water, at least we thought we had no water, until someone “discovered” it for us a few weeks later. We tried in the beginning to boil water brought in a pitcher over the road on sub standard coal dust in the grate.

I had decided I wanted to move to London when very young in fact, just about to leave home. My friend Jamie Gough, whom I knew in Oxford, had a Ph.D. from Corpus Christi College while I had just done A levels at Oxford College of Further Education. Jamie had heard about people who had moved into buildings just north of the architecture school they were attending. Only a few had moved there then; we went to Drummond Street, a small street running between Euston Station and Hampstead Road and chose a house between Diwana, the first and only vegetarian Indian restaurant in London, and a small corner grocer’s shop called Vines. With Corinne Pearlman, an old friend of Jamie’s, we chose a house because it was pretty; most of the other squatters were around the corner in Tolmers Square.

We felt safe in our house almost immediately after gaining access. The fact that there was starting to be many of us in the area made us feel much more protected. The squats developed, opening up fast. Soon even North Gower Street seemed to have squatters; each road had its separate logic, its mini identity within the whole. While nobody mapped out the limits and edges to our community, we still knew exactly where it was, where it stopped; the space had its own natural triangle edged by main roads and station.

We were afraid of the police and we were not. At one level we were unrealistic and almost naive about the way the full force of the law could affect us. At another level we had experienced battles with the police at Troops Out demos, for instance. Much time was spent in anticipation of confrontation.

Other groups seemed more continually at battle. Tolmers felt safe for the most part. In a way we felt we had control over our patch, again somewhat naive, in retrospect. The Dawn Patrol was an early-warning system, run on strict rota, where almost all of us would take it in turns to scour the streets from very early in morning to look for bailiffs. But this only happened at very high points of expected and imminent peril and towards the end of our time there. All was somehow protected by our own organization, contained within our own sense of control.

We felt protected by the law of squatting; at least we were always reciting that particular part of the law. Once we had claimed occupancy, a very formal procedure would have to be carried out by the bailiffs in order to get us out. We knew our relationship to the court and the various stages we had to go through. All that changed in the early eighties. Also we were very young, on the whole without children, and the relation to permanence was not quite the same; in the beginning it was not the home it eventually became.

At Tolmers people arrived, friends of friends; it expanded through and by word of mouth. As explained, we had a sort of monopoly, at best naive, at worst natural and unruled. I really did tell the people who wanted to move into the house next door to us in Drummond Street that it was “already bagged”; schoolgirl slang for taken. There were no real rules, but a protective naturalness dominated. Be yourself, have faith in the moment. Much of this for me was to do with my extreme youth; I was seventeen when I moved in, so I grew up with the squat, gaining politics, knowledge, and organizational ability over seven years.

The groups: Trotskyists, Eastern European sophisticates, community types, architects, lawyers’ friends, trainee lawyers. But a real homeless person? There was help and advice but, as now, the face of homelessness is often hidden by practical dependence on friends and family. When are you officially homeless? When you have been evicted? But were you homeless before? When is the caring member of the family actually a carer? For us instead it was a way to be away from home, a place to think, to live, to organize, and to discuss; all in the very center of London. Of course it would be punitive, impossible, to pay rent and study in the same way, almost impossible to embark on a poorly paid beginning of an eventual career.

The first people in the band of squatters, the students at the Bartlett, were ambitious, idealistic, making real life part of their studies and the other way around. Then others, individuals, great friends, total strangers, would move in. Even control over who was to share a house would crumble. The two graduates from Oxford, for instance, who rightly ignored my claim to the house next door, moved in with a total stranger and we all soon became friends.

After a short time you got used to people’s fascinations, the different politics, which seemed so very intense at the time. Apparently minuscule differences between us could, and would, be acted out in life. We learnt the difference between theoretical positions, for real. Factions, splinters, nuances, differences, those who chose to enter the system by stealth against those who wanted to confront it directly. Being pushed to support the miners’ strike versus a campaign to stop the closure of the Women’s Hospital. Single issue versus total overview. Meetings, meetings, all the time – well, for some of us, for others just a hanging-out sense of difference, a lethargic, stoned, amorphousness. From communal type to local activist, from trainee solicitor with social democratic leaning to anarchist, it was a privilege to be in a playground where reality and belief could be tested and tried. Instead of virtual reality, it was reality, yet all with the air of a game about it.

The pleasure of living freely in a world within a world was palpable. The seventies seemed to be very much about differences, collecting together, allowing, encouraging, and tolerating. Different gangs, sexualities, different approaches to property and the state. These were liberal times both sexually and emotionally, but revolutionary times, we hoped, politically. The security this approach allowed made safe and cozy sense. Returning home was always a relief; Tolmers provided an alternative security within London.

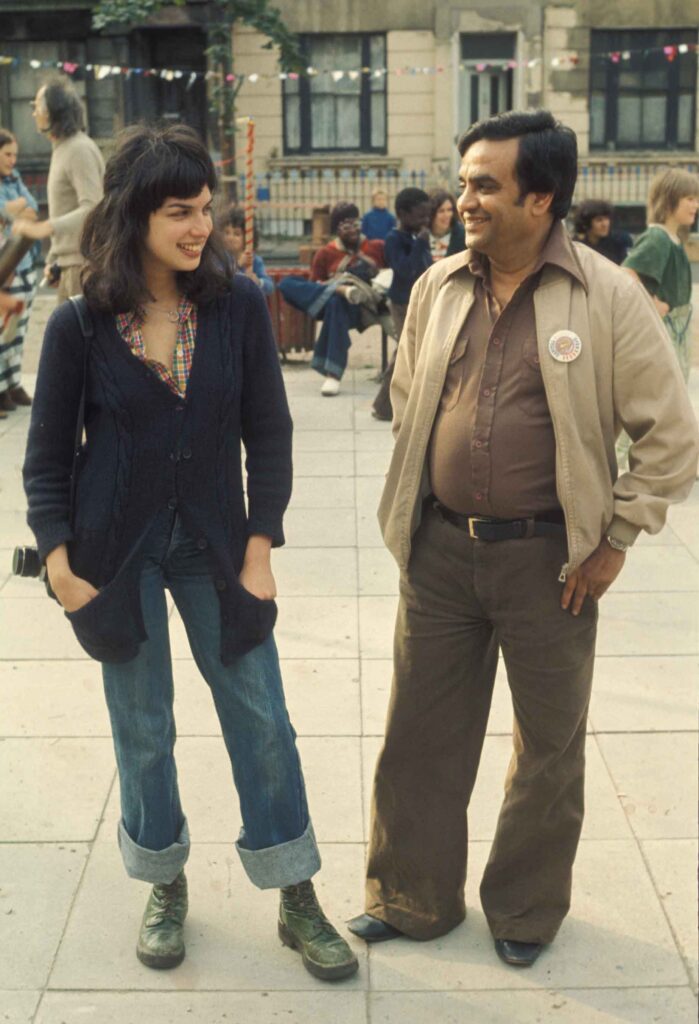

Squatting gave us the chance to study, work, think, and do nothing, without worrying about rent. This made such a difference, it created a great deal of time for work, repairs, political action, and festive celebration. How did we get to understand so much? There were negotiations with local councillors, people still politically active starting on their own political careers. The community of Tolmers broadly covered the strange, almost forgotten, triangle above Euston Road and between Euston Station and the Hampstead Road, Despite some building, it is still a quiet, separate comer, albeit in the middle of the city. There had been a housing struggle in the area before, the architects knew that, but this involved local people, while our movement came from outside, on the whole, bringing a sort of earnest “goodness” about it. People who lived there were welcoming. The halal butcher, the sweet shop, the fancy dress and army surplus and, of course, the pub or pubs. People were kind and giving, and we were polite on the whole.

lt was one of the original Central London immigrant patches, sporting a range of Indian shops and restaurants; the relation between squatters and locals was absolutely fine, as far as I can remember. We formed close everyday friendships. Jeyant Patel’s first and only vegetarian Indian restaurant in London was next-door and he often fed us for free.

John and Ethel Vine on the other side of us ran a very small corner shop.

The main point in terms of people who were already living there was that Joe Levy, the speculator, was leaving houses empty, preferring to remove property from its function, apart from an ability to gain financial value. Rents were never enough, tenants meant trouble, so he just sat on the empty land. The fact that we moved into the buildings and did them up to a point was enough to endear us.

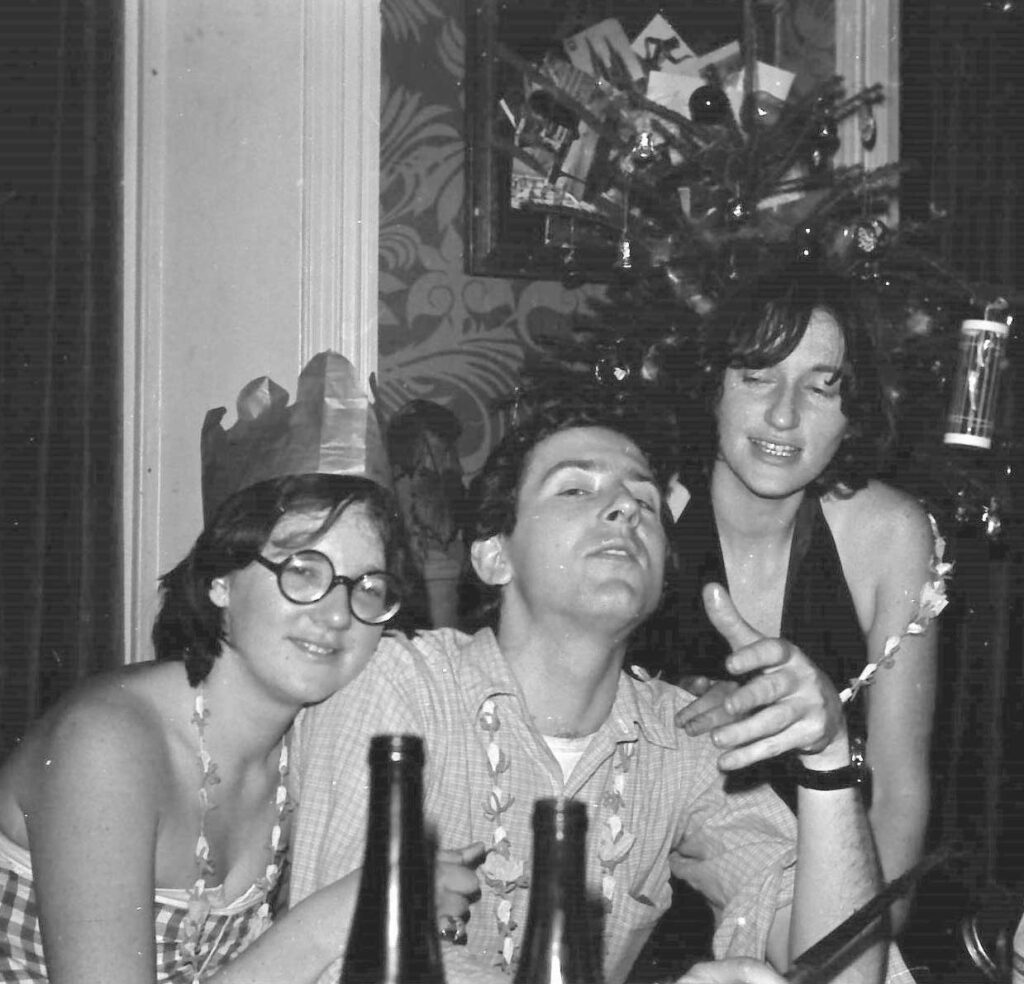

All was predominantly sociable. There were those who felt it their sole responsibility to organize parties and fetes, to liaise with bands, to coordinate with Jeyant Patel on the vats of Indian food, to set up the sound system for the dancing and, of course, assemble the random classical quartet to play in the street.

It became fashionable for visitors, especially radical lawyers, to say they had had dinner at number 12 Tolmers Square, the house we moved into after Drummond Street. We had wallpaper from the smart, high-bourgeois wallpaper shop in Kings Road. A piano, a basic kitchen, a nice range of disparate china, and large-scale cooking equipment.

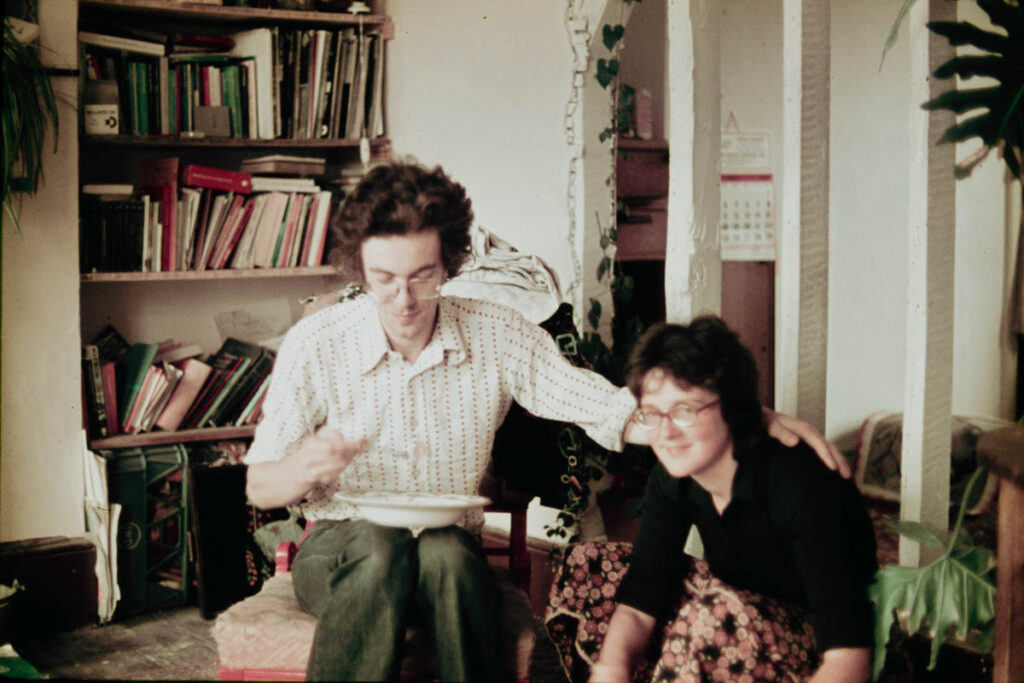

All very cold, though, rough, but all pulled together everyday by and for meals and, almost continual, wine. We did do repairs on the near-derelict building, but we never exactly made it in any way comfortable; we could never attempt that. Our conditions were basic, there was water, once found, but no bath or shower or sink other than the one in the kitchen. The drainage system in Drummond Street had been more than basic in that we would pour all slops into a giant tin bath which we would then empty out into the backyard from the first floor window, but in Tolmers there were drains. Floorboards were missing from the stairs. The norm was to expand space rather than block it in. Knocking through walls in my case, in 12 Tolmers, leaving the supports, to take over the whole floor of the substantial Victorian town house.

We did sometimes have gas; people became excellent at simply plumbing both gas and water; hooking up and turning on.

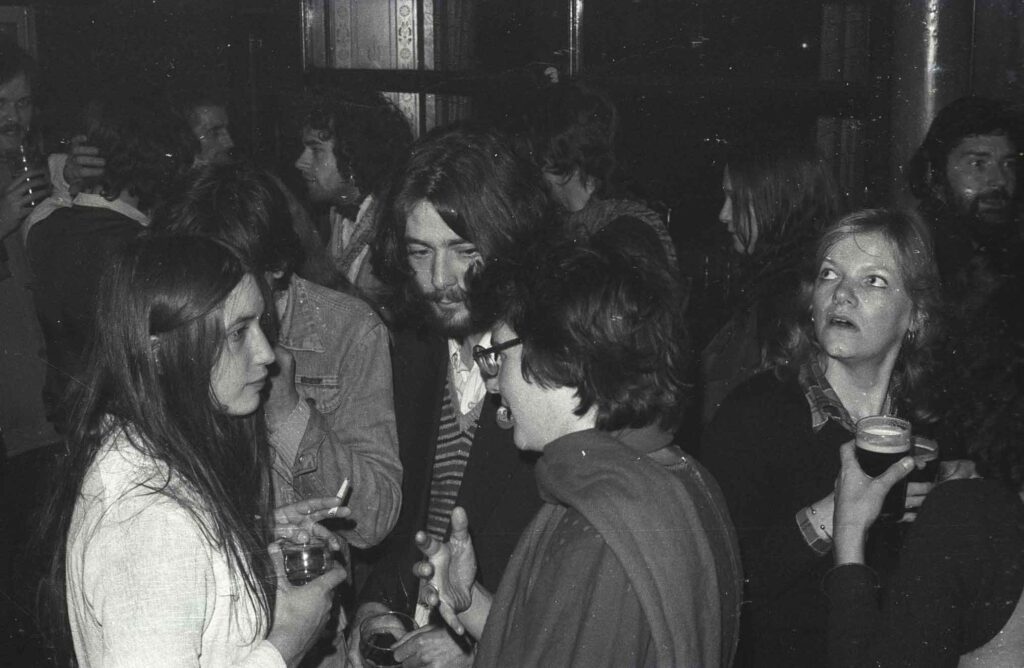

We had parties in the square, in each others’ houses, and in empty shops taken over specifically for the purpose. Almost every house became squatted in the square, and you would stand on the crumbling, dilapidated balconies there to wave to friends in number 6, for instance.

We would head to Hampstead Heath on the 24 bus with saucepans straight from the stove. Friends visiting from Italy would sing old resistance songs all the time; a complete caricature of a seventies notion of struggle.

We would take the ferry and train to Paris for the Festa de l’Unita and get excited about the imminent revolution on the Iberian Peninsula, often all at the same time as a proper job, teaching at college, studying, signing on, being a trainee solicitor, organizing a poster collective, and starting what turned out to be a major food empire.

Men and women lived together normally. Obviously, not all the men did a massive amount of work, but the split between lazy person and active domestic person was a split along very different lines from the sexual divide. My great friend Jamie would overreach himself by starting on some elaborate cooking, having called a Gay Liberation Front meeting, and someone like me would end up finishing what he started; letting people in, stirring the pot. Some people were super-practical and others seriously challenged; it was often best not to know how to do something because you would then have to do it. We made places lovely but in a stylish, povera way. It was the eclectic aesthetic of the time, a desire for elaborate retro design, lovely old found furniture.

We could live in different groups and relationships, men and women would live apart and together; it was always sensible to have a room of your own, though, whatever your sexual expectation and reality. My household remained consistent, in that some of us stayed together all the way through, but it expanded and changed as well. Friends moved in and out, couples split up, necessitating a move by one to another house. Couples existed within an already individual culture and this made a difference. We cooked together, taking it in turns and usually catering for more than just the people in the household. Food then was far less varied, the range and choice limited by the era as well as a lack of money. A man called Jo the Meat Man would bring us meat from an undisclosed source. It was good, once thrashed by the end of a rolling pin and fried in garlic and oil. We had bread from the normal corner shop, bought at the same time as a pint of milk and ten Woodbines. But then the Bakery opened in North Gower Street, providing the beginning of alternative food. We, on the whole, were not quite so breathlessly reverent about this kind of thing, but John and Vera really did care about the field the wheat had come from, which made us laugh. A sort of religious silence seemed to surround their place.

We smoked dope, of course. Drink was then, as now, the most important and overriding force. We went to the pub all the time, drank wine at home, and had enough money for this.

We lived together easily because we did not do what is expected in a communal situation. Some people might be encouraged to tell the truth, but we have always tended to be economical with it. If someone irritated you, you did not immediately say what you thought; this, in retrospect, is probably the most English, repressed, middle-class way to go about things, but it also did some good. A few of us ended up living together for much longer than the average marriage, and Corinne and I, who moved in together in 1973, still do. I suppose we used to think that things would change somehow anyway, that life both outside and inside is always so eventful and exciting that annoying individuals could be overlooked for the time being.

Democracy in living conditions was not always the point, because in a way we already had it. Politeness ruled; manners, kindness, greetings, sharing rather than principled stands and discussions. Probably we were so involved in the very complexity of political change and action to precipitate it outside that we tended to err towards something else at home. The personal/political split was constantly discussed and debated, but home was not a theoretical battleground. We were in a position to grab an overview, pull ourselves up in a very real way, to try to grasp what was happening to us.

The squat was always a struggle against new development and speculation. We went through many struggles and campaigns between 1973 and 1979. We managed, somehow, to force the Council to compulsorily purchase one side of the square to ensure Council housing there when we leave; we fought Levy; we fought a campaign for housing for single people; we talked of planning, of the height of prospective development on the other side of the square. I know it made a great difference to that corner of central London. There is new housing there, a strangely un-majestic, more enclosed square, but definitely not what would have been if we had not been there.

I remember doing the rounds of houses with Community Jo, as we called him. As I asked for 50 pence per household towards the struggle against Levy – a levy on Levy -, Jo was just asking for pulses, for food in kind, to aid the struggle. We worked well together in this way, at that point.

Just before the eviction in 1979 we ended up with a large picture across the very front of the Observer Sunday newspaper. “London’s oldest squat evicted.” A line-up of those left, along the balcony. Leaving was very sad, It was not a shock, we had organized and prepared, and symbolically as well as actually fought this moment. Loyalty to a place is as strong as anything, I feel. The piano was brought down and a friend still played it in the square. It was heartbreaking passing on a bus a few days later to see our smart wallpaper exposed to London. Everything turned out, inside out.

It was a turning point anyway; Thatcher had just come in and I knew it would all change in so many ways.

We moved first to a Council flat where we had managed to get re-housed. Too small. We had run that excellent last campaign in Tolmers for housing for single people – the slogan “Single people need it too” was funny and serious. We fought for the council to show loyalty to people who lived differently, in different configurations.

I now live in a large house in the centre of London, just down the road from Tolmers. We moved here in 1979. The house belongs to the British Museum, we pay rent. Seven of us live here, and my daughter.

More stories

Academic leg up

by Tim Wilson

I changed from being a straightforward academic and amateur lefty to being someone who believed that the skills I had could be put at the service of urban communities.

Those were the days

by Michael Fitzpatrick

We enjoyed the flourishing social scene centred in Tolmers Square, where a derelict bank was the scene of orgiastic gigs and periodic carnivalesque celebrations.

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

Room at the top

by Paul Nicholson

All the lonely people Where do they all come from? All the lonely people Where do they all belong?

Tolmers picaresque

by Oli Arditi

Tolmers Village was a great place to be a kid—sometimes a dangerous place, for members of the small gang I ran with, and for the adults we occasionally terrorised.

Escape from America

by Meg Rosoff

I couldn’t believe my luck and spent the rest of that year in a kind of happy daze. All those amazing people.