All the lonely people

Where do they all come from ?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong ?

Lennon/McCartney

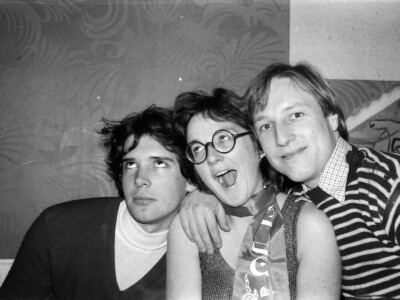

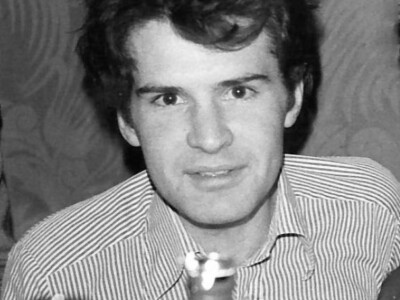

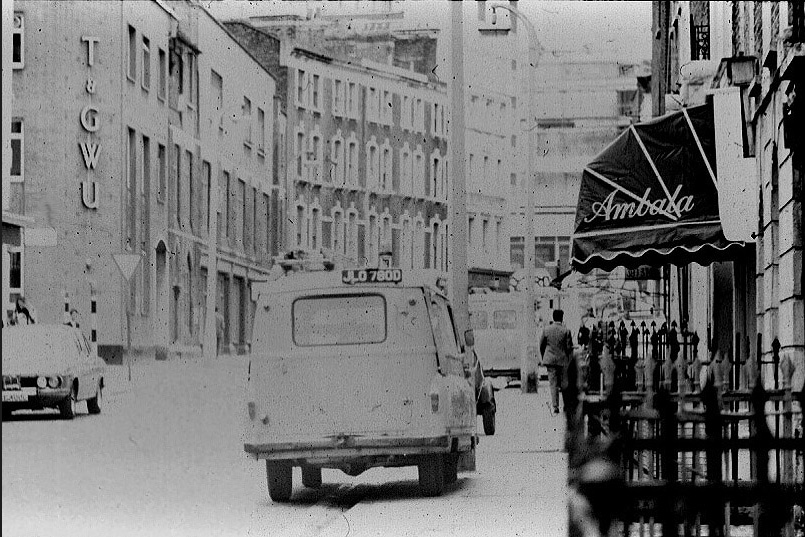

When I first arrived in Drummond Street George was living in the room at the top of the house. Not that anyone saw much of him. He would appear from time to time in the kitchen to make a cup of tea, or on rare occasions to eat with us. Yet I can still picture him, a slight figure in his worn out green cord jacket, straggly sandy hair and beard. Profoundly gentle, sad eyes behind cheap spectacles, a flicker of a faint distracted smile passing quickly over his pale features.

We knew little of George, other than that he was working on genetics research at UCL, through which connection, in some indirect way he had met Ches. He never spoke about it. He never spoke about being a Christian either. I’m not sure exactly what he believed, or if he belonged to any denomination or church, but it drove him to walk the streets in search of lost souls. In the city they were not hard to find.

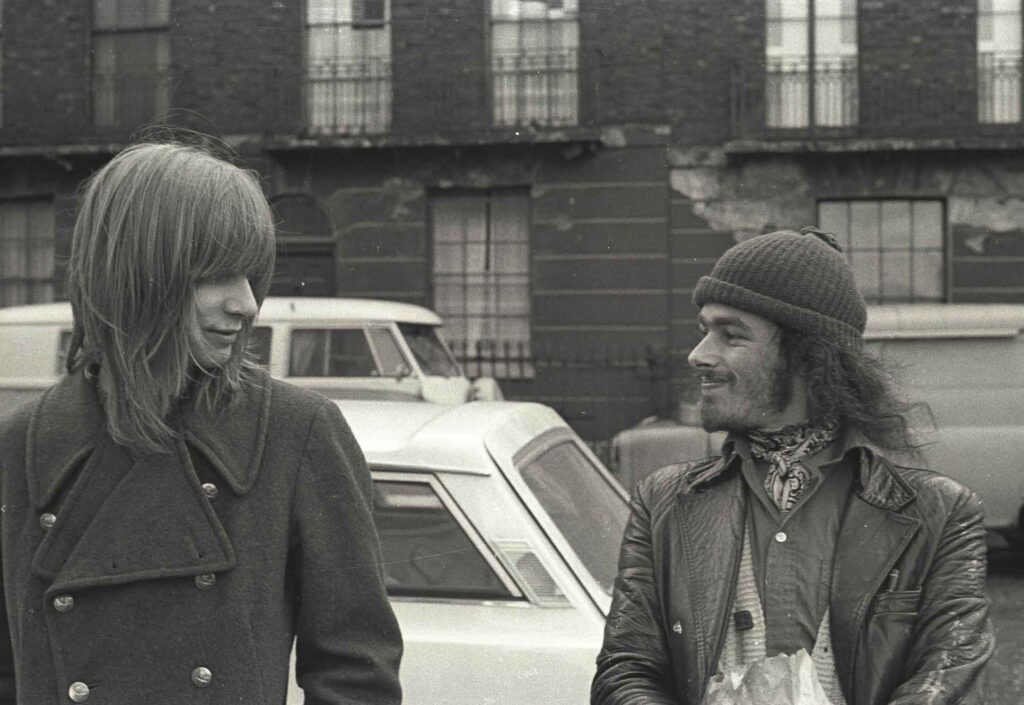

One day I went down to the basement kitchen to find a small gathering. I can’t remember the company, other than George – who remained somewhat apart from the group – and a guest of his, who was introduced as Peter. They seemed from the first sight of them together the most unlikely companions – Peter being as loud and profane as George was quiet and studious. A battered wide brimmed hat hung down his back attached to a cord around his neck. He was wearing threadbare donkey jacket, greasy jumper and open necked shirt and a pair of dirty brown canvas trousers. A crutch lay propped against the wall behind him, and one of his legs was missing below the knee. He drank frequently from a bottle of cider, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand before squeezing some blues from a harmonica or speaking with some fervour about Leadbelly. From time to time he reached for a tin containing a quantity of stale tobacco accumulated from butts retrieved from the pavements, and rolled a cigarette. Hands and stubble beard orange streaked with the stain of nicotine and tar.

Perhaps they bickered and argued even then, like an old couple, – perhaps it was at other times – it hardly matters now. George was set on redeeming Peter from his alcoholism in some fashion, but his mild rebukes drew only hostile and dismissive responses.

Soon after this first encounter, it became apparent that Peg Leg Pete – a name, that if he did not introduce himself by, he revelled in – had become a fixture in the house. He and George shared the room at the top for a month after this – perhaps two. Occasionally, they might be seen heading off down Drummond Street together, doubtless towards one of the nearest pubs – the Exmouth or the Jolly Gardeners. After a while, things clearly became too much for George and he vanished. Perhaps we saw him in the street afterwards and he ventured an explanation. Peter, however, remained and as time passed, we came to appreciate how intolerable it must have been.

Peter claimed to have been a journalist before his descent into the antechambers of oblivion –and it may have been true – a notoriously hard drinking profession. In his more personable moments he displayed the traits of someone with a well educated background, but these were few and far between. How long he had been in the company of strangers, ragged people and passing through the shadowy margins is a matter of conjecture. He once told us the story of how he came to lose his limb, clambering over a wall while being pursued and falling, catching the leg on a hook, where he remained suspended until the police arrived.

More than once Peter would come back drunk after closing time, and having lost, or been unable to find his key, would simply shoulder the door open. If we were in, we’d come rushing down – no doubt fearing the worst on the first occasion (the police or bailiffs) – to find him sprawled on the floor in the hallway. We’d help him up and try to explain that it would be better to ring the doorbell or knock rather than bust the door open: but he was too far gone to take anything like this in. Or simply didn’t care, stumping off up the stairs leaving us to fix the lock. Other times we’d be sitting in the front room on the first floor and he’d come crashing and stumbling through the door, collapsing in heap.

Sorry, lads he would say eventually, lost me balance. Got a snout?

And there he would stay, for what seemed an eternity, declining assistance, until he decided to allow us to help haul himself up and make his way upstairs, us behind with a hand on his back as some measure of safety. Occupying a room reached by two flights of stairs presented obvious difficulties for someone with an amputated lower leg, not least of which was the fact that the toilet was outside in the back yard. Consuming large quantities of alcohol on a regular basis did not help matters, and our increasingly unwelcome housemate did not attempt the frequent journeys that would have been necessary. As we rapidly realised, Peter’s solution was to use the ample supply of empty bottles that he had at his disposal to relieve himself into. When these were all full, the contents would be flung from the window into the back yard, making a trip across the flags to the closet a hazardous journey for the rest of us.

Had Peter been of a different temperament, the possibility of re-arranging the occupancy of rooms might have arisen. As it was no-one felt inclined to contemplate this, least of all Harry, who had the room directly below the one that George had originally occupied. The ground floor of the house, formerly a shop, served as the office of the Tolmers Village Association, a local residents group, and was out of the question. And so the bizarre scenario continued –the crashing of doors in the night, chancing on Peter comatose halfway up the stairs in a pool of urine, furtive glances, frustration, incredulity and some measure of guilty feeling.

How long this went on it is hard to recall – possibly months – until there mercifully came the day that Peter did not return from one of his drinking forays. Perhaps he found somewhere else, or equally likely ended up back on the street, in hospital or jail.

Some considerable time later we heard that George had committed suicide, cutting his wrists, in Lush’s Flats, a small squatted tenement building in the continuation of Drummond Street just across Hampstead Road.

Postscript

Many years later I learned that George Price was a person of some significance in the fields of mathematics and genetics.

I was contacted by Oren Harman, who was writing a book about him: ‘The Price of Altruism – George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness’. I provided him with some background information along with the story above and met his daughters who came to London to meet Oren.

We walked around the Tolmers streets together and visited George’s unmarked grave in Islington and St. Pancras Cemetery in East Finchley, with the film maker Adam Curtis and Jeremy Johns from the British Library.

Harry is also buried there in an unmarked grave. A letter written by George Price to a doctor about Harry provides a fascinating insight into both of them.

Read more about the author Paul Nicholson

More stories

The best thing I ever did

by Douglas Smith

Number 12 was damp and stank of cats, the ground floor window was bricked up and there was water but no plumbing.

Squatting law expert

by David Watkinson

“My learned friend has a whole army of people to assist him, while I have only my solicitor and a clerk”.

Bourgeois squatting

by Corinne Pearlman

It seemed like the right way to live. It felt very comfortable for me, living with a lot of people. I’ve got various lives in different places, but that communal life is really important.

Second-hand geyser does the job

by Colin Ferguson

I learned a lot of DIY skills. It was amazing to find out you could do it.

Curating the archives

by Nick Wates

Its hard to throw stuff away and its never a priority to sort it out. So I carted it all around for decades.

The legal battle

by Patrick Allen

Outside the court there was relief and jubilation for the squatters but consternation for the property company and their lawyers.